Research / Geopolitics

French military, The lonely bastion of European defence

It is certain that the war in Ukraine entered as a game changer into defence thinking. This is no different in France, even if the country has always tried to remain in the pond of globally big fish. In spite of the fact that Paris has always been a fundamental member of the Trans-Atlantic alliance, just like in the past when it acted on its mistrust of Washington, it is yet again in a tug of war with some of its NATO allies. Nobody knows what kind of an effect this current war will have on France’s defence and its place in the Euro-Atlantic defence structure, but it is already visible that Emmanuel Macron will continue his second term in the same spirit of triggering deeper military cooperation with his European partners, but at the same time it is very unlikely that NATO’s role will diminish on the continent in the foreseeable future.

France the lonely bastion

Why would we call France the lonely bastion of European defence? Well, there can be numerous explanations for that. Firstly, we can mention the hard power elements, such as the fact that France is the only nuclear power in the European Union after Brexit, it occupies a permanent seat in the United Nations Security Council, and last but not least it possesses the biggest armed forces among EU member states, that in 2019 counted 304,000 personnel[i]. Secondly, there are also soft power elements that might position France as the leading figure of European defence. France, and especially its foreign policy-wise ambitious young president who has recently been re-elected for a second term in office, are determined to construct a viable European defence structure, that - if not entirely independently from NATO - would be capable of ensuring security on the continent. We have to give some credit to France in these endeavours as it is true, that it can deploy formidable military capacities when compared to those at the disposal of its European partners. It is only the Italian armed forces that can measure up to the French with 342,000 military personnel, otherwise Germany’s only counted 184,000, Poland’s 189,000 and Spain’s 199,000 in 2019.[ii] However, military capacity is not the only thing that matters when it comes to defence leadership within a community of nations, diplomatic initiative also plays a crucial role.

Looking at it from a historical perspective France has always been struggling with becoming the continental hegemon of Europe most of the time in competition with Britain for supremacy over the seas, and with Germany for supremacy over the land. Now, the geopolitical playground after the Second World War was reformed in such a way, that none of these European rivalries mattered any longer, as the bipolar world order installed. France in 1945 counted among the winners of the war, thanks to the efforts of General De Gaulle and despite the collaboration of the Vichy-government with Nazi Germany. Yet, Paris soon had to realize that it has no place in the club of the superpowers, a position it shared with the United Kingdom. Both the economy and the army were in a deplorable state, and France could only be helped onto its feet by the United States, in the meantime integrating into the Western block. But France also realized, after the pink cloud of victory had dispersed, that in order to maintain anything of its previous status on the global stage it needed to expand. Expand, not in a territorial way, but an ideological and an economic one. As a result, and because West-Germany also felt somewhat similarly, these two centuries-old mortal enemies decided to cooperate in something that evolved into the European Union we know today.

The European integration at first was a purely economic cooperation where foreign and defence issues were way off the table. However, this situation has been changing for quite some time now, and today, there are signs of a political union being formed. This progress is being accelerated by the entrance of the heavily and determinately Europeanist President Macron, who in his 2017 Sorbonne-speech, entitled “Initiative for Europe”, prompted partners to strengthen European defence. Let us not forget about the American element though, the defence umbrella provided by the NATO that almost every EU member state enjoys.

Stormy years with NATO

After the Second World War, and at the beginning of the Cold War France joined the NATO in the hope that it is the defence organisation that is able to ensure the country’s, and Europe’s security against the ghost of a possible Soviet invasion. But General De Gaulle did not want to entrust Washington with the exclusive rights to defend Europe, he took steps instead to enhance French military capabilities and to prompt European partners for further cooperation. Yet, it has never been actually a question that France should be part of the North-Atlantic alliance system and that it was the framework that could best ensure its security. Paris was one of the twelve members that founded the North Atlantic Treaty Organization in 1949. The alliance’s main character is that it is a collective defence organisation which is manifested in the Fifth Article of the Washington Treaty[iii] where allied parties consented to act as one in case one of them falls under armed attack.

As a consequence of French appetite for grandeur and gloire, of General De Gaulle’s mistrust towards the United States, and his genuine vocation to defend the European continent and France with it, he withdrew the country from the integrated military command structure and it was only Nicolas Sarkozy more than forty years later to reintegrate Paris into the full scale of the alliance. This does not mean whatsoever that France had ever ceased to be member of the NATO, only that the French military capabilities were removed from under NATO command. Also, it has never been put into question that France remained an integral and in fact crucial member of the Western alliance system.[iv]

Another very important element of defence and security for De Gaulle’s France was the nuclear capacities, which at the beginning of the Cold War were generally considered to be the cornerstone of global big power status. The United States at the time was not in favour of new emerging nuclear powers on the international scene, because it was afraid of a possible proliferation. This struggle and inside rivalry happened the same time France was engaged in the Algerian war, and was facing the harsh realities of its deteriorating global standing. To sum it up, France, because of several reasons, was highly frustrated by and struggled with adjusting to the Cold War system. General De Gaulle saw a risk in relying entirely on the American defence umbrella, therefore he searched for another path that resulted in Paris’s exit from the integrated military command structure in 1966.[v] So when today we hear of the French President speak about an independent European defence it is only natural that we anticipate history repeating itself.

When Force de Frappe went out of fashion

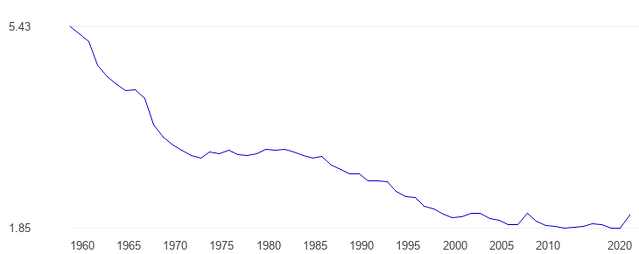

When the Cold War in Europe came to an end, France just like the whole world had to reconsider its defence structure. There was a new world order being formed dominated solely by the United Sates, and Paris had to restructure its military force and adjust it to this new scenario. To put it plainly, the Force de Frappe advocated so fiercely for by General De Gaulle simply went out of fashion, military spending continually diminished from 5.43% of the GDP in 1960, to around, sometimes even below 2% for the new millennium. Indeed, the old-fashioned regular military concerns almost disappeared, but at the same time new ones emerged, such as mass terrorism, and destabilisation of countries on the periphery and in the neighbourhood of Europe. Beginning from the 90s though there was no more one easily definable enemy, but multiple threats of various natures. One thing however, became a lot more desirable for France, the results of which are only becoming visible nowadays, and that is the enhanced activity on the European level.[vi]

Figure 1: French military spending in percent of GDP. Source: theglobaleconomy.com[vii]

After the fall of communism in Europe and the appearance of new threats outside of the continent a greater focus had to be sacrificed on research and development (R+D) especially in the military field. As a consequence, in France innovations started to be introduced utilising the massive financial and human resources contributed for the cause. It is important to note, that since the end of the Cold War the military became highly institutionalised, therefore politics have a great influence on how the defence industry operates.[viii]

The current state of the armed forces

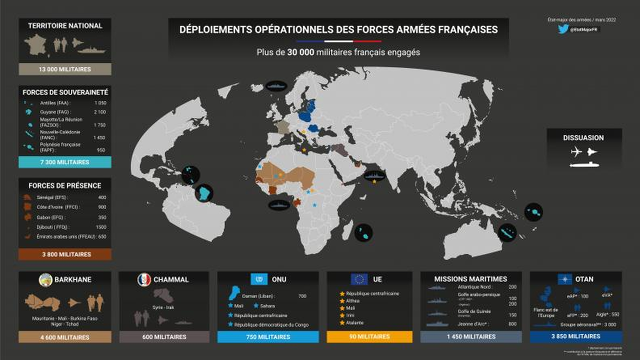

The French army is a globally present one both on land and on sea. The deployment of the French armed forces can be defined by these five principles: to know and to anticipate, to prevent, to deter, to protect, and to intervene. Obviously, the priority of the French military is to defend the national territories, including those overseas, yet there are several foreign missions France is engaged in too. As Figure 2 shows France possesses a remarkable armed force, with more than a total of 30,000 troops deployed on the national territory and in foreign missions all around the globe.[ix]

Figure 2: French military operations around the world. Source: Ministère des Armées[x]

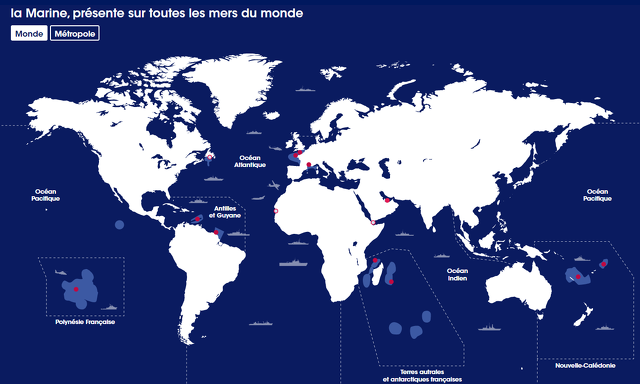

If we want to look deeper into the constitution of the French armed forces, we can see two major divisions: land forces and the navy. The former, in addition to guaranteeing homeland security is engaged in out of area missions such as Operation Barkhane in the Sahel region with a main focus on counter-terrorism, Operation Chammal in Iraq fighting the remnants of Daesh, Daman in Lebanon and Operation Lynx in the framework of which France contributes to the security of the eastern flank of NATO.[xi] As for the navy, it is also a globally present force which patrols the waters of the world with one aircraft carrier and three helicopter carriers and nearly 100 vessels. Figure 3 indicates the presence of the French navy which is mostly concentrated around the French metropolitan area and the proximity of its overseas territories.[xii]

Figure 3: Global presence of the French Navy. Source: Cols Bleus[xiii]

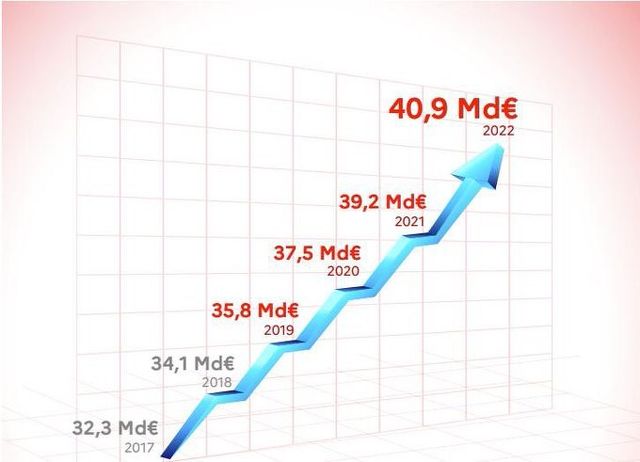

To give an overview of what the French defence capabilities look like today and what we can expect to happen to them in the foreseeable future let us have a look at the programme of Emmanuel Macron according to which he became elected President of the Republic for a second mandate. Since 2019 €198 billion were spent on the army which also triggered a 3000-strong increase in the number of personnel. Continuing this, President Macron pledges to spend a further €295 billion over the period 2019-2025. France also aims to engage in the so-called space race and to enhance its capabilities against possible cyber-attacks. Last but not least I would like to emphasise that the whole defence programme is built in a way that it is embedded into the now-forming European defence architecture, the President prefers to call strategic autonomy.[xiv]

Figure 4: Budget of the French Defence Ministry. Source: theconversation.com[xv] (Md€=billion€)

We can certainly agree that the nature of defence has changed considerably over the last couple of years. Today, it is not necessarily the borders that need defending, and countries must learn how to organise their defence without borders and it is also important to establish defence alliances as most threats cannot be overcome by lonely bastions. Since Emmanuel Macron entered into power in 2017, he does everything in his power to remove his country form being one and introduced a new doctrine in European defence: “A sovereign, united, democratic Europe”. Upon his initiative the European Union created the European Defence Fund and further developed the Permanent Structured Cooperation while strengthening the European common defence, all measures are meant to create a more independent European security.[xvi]

Tug of war within the same team?... again

The tug of war manifested around 2018-2019, when the French and the American ideas for the future and present of the NATO clashed. We may not know exactly whether the differences between Donald Trump and Emmanuel Macron derive from their different styles or their different visions but they could not exactly see eye to eye around the NATO Summit organised to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the military alliance.[xvii] On the one hand, the refusal of Washington to act as referee in the Macron-Erdogan struggle, and on the other hand the explicit wish of Trump to withdraw from European defence both resulted in serious tensions. While France feels that the USA does not do enough, Washington feels that European partners are taking advantage of using the NATO framework the US contributes to the most. It is for certain that France imagines a different role for the NATO than it has today, but so does the US, however these new paths may not end up crossing each other.

It is clear that France wants to change the way NATO works, maybe even its scope and structure. There are several push and pull factors that we can identify behind this policy. In the Trump-era the United States gave the impression that it is not very interested in European security any more, and that Washington rather wishes to relocate its energies to the Indo-Pacific region. Having understood this, Emmanuel Macron made it his job to draw the attention of European partners to the fact that the continent is almost defenceless if it cannot rely on Washington any longer. This anxiety of his might have been perceived by the Euro-Atlantic alliance as an attempt to disintegrate NATO. The peak of his straight-forward rhetoric about NATO was achieved in 2019 when he claimed on the pages of the Economist that he considers the defence alliance to be brain-dead.[xviii] The tug of war that evolved between the Trump administration and the Macron government derived from the following three problems: Firstly, neither France nor Europe could remain completely certain that they can count on the American defence no matter what. Secondly, and highly related to it, President Macron started to doubt the reliability of Washington as it engaged ever more frequently in unilateral decision-making without consulting its allies. The third problem for France at the time was that the NATO remained fixed on the Russian axis, whereas for Paris terrorism seemed to be a more urging security concern.[xix]

As for the defence industry France can benefit from being a member of NATO, but also encounters some difficulties related to this. France does not approve of the notion that all allied member states should buy American capabilities, this way deteriorating their own defence industry output, therefore Paris attempts to limit American hegemony in this respect. Consequently, France is a lot less dependent on NATO and Washington when it comes to its defence, yet it continues to see the raison-d’être of the alliance, not on the political but rather on the military-security level.[xx]

Ukraine as a game changer

Even before the war in Ukraine started many believed that the year 2022 might be the moment in history for France to step out from the shadow of the United States in defence issues. Firstly, because of Donal Trump and the aforementioned clashes between him and the French President, then because of the AUKUS deal struck by the Biden administration, experts anticipated a rupture in Franco-American relations with long-standing effects on NATO. Secondly, the exit of the United Kingdom from the European integration and the European defence structure it seemed to be the perfect opportunity for Paris to assume leadership over European security. Thirdly, and most recently, the Russian threat building up in the beginning of the year seemed to have started to convince European leaders that it was high time they created the infamous European Strategic Autonomy. Fourthly, currently France occupies the seat of the rotating presidency of the Council of the European Union, therefore Paris holds a better chance than ever to influence partners and the agenda itself. Now that we are well into the armed conflict between Russia and Ukraine, and speeding ahead towards the end of the French Council presidency it is still not clear whether President Macron’s EU counterparts will give into the idea of building a new non-NATO security architecture meant for the European continent only.[xxi]

With the unfortunate war situation that has formed on the eastern periphery of Europe France’s European partners and the United States itself acknowledge that a certain level of military capability in Europe is needed. Apart from what has been happening at the Brussels negotiating table, Emmanuel Macron, right when hostility between Ukraine and Russia started to grow, initiated his quest to trigger the peaceful settlement of the tensions. We know now that his efforts were in vain, as a war did erupt in the end.

Due to the war in Ukraine, France under the egis of NATO sent 4 Mirage 2000-5 aircrafts to Estonia and engaged French fighter jets into air patrols over the territory of Poland and deployed some additional capacities in Romania.[xxii] Up until 2 May 2022 France sent €100 million in humanitarian aid to Ukraine, furthermore, 615 tons of equipment were transferred to the country including medical and agricultural products. In addition to this, defensive lethal weapons have also been sent worth €100 million.[xxiii]

Now with the war in Ukraine there are again voices emerging that say that France should reconsider its NATO membership altogether. Especially because the war started at a time when the campaign for the Presidential elections was on-going, and candidates did not hesitate to grasp the opportunity and to use it for their own benefit. Emmanuel Macron won the presidential seat again in 2022, as he did in 2017. Despite his vivid criticism of the paralysed NATO, he insists that France should remain a part of it, but at the same time he also advocated for a strengthened European defence as he sensed that Washington is not that keen to protect Europe as it used to be at the beginning of the Cold War. Perhaps his assumptions are being proven by this current war taking place on Europe’s doorstep. His main rival and contestant in the second round of the elections, Marine Le Pen, on the contrary, urges that France should be removed from the North-Atlantic alliance. As for Jean-Luc Mélenchon who is now likely to become Prime Minister after the legislative elections agrees with the leader of the National Rally insisting that France should have nothing to do with NATO.[xxiv] In spite of the fact that these three are major political rivals, we should bear in mind one thing: all three of them pronounce criticism related to NATO and that tells us that France indeed has started to look for alternatives for ensuring its security.

Despite the destruction that is closely linked to it, France can draw some conclusions from the war in Ukraine for the sake of the development of its own capabilities. Most importantly, that countries must not let their conventional capabilities degrade while upgrading the means for fighting in low-intensity, asymmetric conflicts, as the age of high-intensity fights is not over yet. This means that France equally has to prepare for hybrid threats which can include regular, irregular and cyber elements.[xxv] As a result, and taking advantage of the security crisis, Emmanuel Macron took the opportunity to draw European partners’ attention to the fact that they need to create a more independent defence in cooperation with but not exclusively within NATO.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it is apparent that France’s security environment changed dramatically since the end of the Cold War and a lot more since the end of the Second World War. France however, still remains a globally present power, that possesses a formidable armed force capable both on land and on sea. Historically it is true that France has always been a key military power on the continent, and it also managed to keep some of its relevance during the Cold War era avoiding shrinking between the two superpowers. Despite all that, from the 90s Paris paid less and less attention to regular security threats and was more committed to modernise its defence so that it becomes suitable for avoiding irregular threats such as terror attempts and cyber-attacks. Nevertheless, with the war in Ukraine the French too had to realize that there is still need for regular hard power facilities.

Another important element in France’s security behaviour is its initiative to lead a more European and less Trans-Atlantic alliance that can guarantee the continent’s security. The current situation can have a two-fold effect on this project. It can align France and Europe more to the United States against Russia, or it can convince European partners to act on the plan of the European Strategic Autonomy and elevate the EU to the military level of the United States, Russia or China. How the war will proceed in Ukraine we do not know, neither can we anticipate how France will act in the future on this sloppy military ground we see around us today, but given the French background I do not think that Paris will hand over the helm to Washington completely and I believe it will try to at least maintain its role in European security.

Bibliography

- “Actudéfense” In: Ministère des Armées, 3 March, 2022.

- "Armed Forces Personnel”, Total – European Union. In: The World Bank https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.TOTL.P1?locations=EU (Accessed: 03.05.2022.)

- “Armed Forces Personnel, Total – France”. In: The World Bank. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.TOTL.P1?locations=FR (Accessed. 03.05.2022)

- “Armée de Terre”. In: Ministère des Armées. https://www.defense.gouv.fr/terre (Accessed: 04.05.2022.)

- “The North Atlantic Treaty” 4 April 1949, Washington

- BARON, Kevin: “It’s Macron’s Moment to Move Europe Beyond NATO”. In: Defense One. 25 January 2022. https://www.defenseone.com/ideas/2022/01/its-macrons-moment-move-europe-beyond-nato/361163/ (Accessed: 10. 05. 2022.)

- BONIFACE, Xavier: “Guerre en Ukraine: quell impact sur la politique de défense française?”. In: The Conversation. 18. April 2022. https://theconversation.com/guerre-en-ukraine-quel-impact-sur-la-politique-de-defense-francaise-181007 (Accessed: 10. 05. 2022.)

- CANTIÉ, Valérie: “Rester dans l’OTAN un peu, beaucoup, pas du tout: ce que proposent les candidats à la présidentielle” In: France Inter 5 April 2022. https://www.franceinter.fr/monde/rester-dans-l-otan-un-peu-beaucoup-pas-du-tout-ce-que-proposent-les-candidats-a-la-presidentielle (Accessed: 10. 05. 2022.)

- CHEVÈNEMENT, Jean-Pierre: “Le <<retour>> de la France dans l’OTAN: une decision inopportune”. In: Politique étrangère. 2009/4. 873-879.

- Défense/Avec vous (Presidential Programme of Emmanuel Macron 2022) https://avecvous.fr/notre-action/defense (Accessed: 10. 05. 2022.)

- “Emmanuel Macron in his own words” In: The Economist. 7 November 2019. https://www.economist.com/europe/2019/11/07/emmanuel-macron-in-his-own-words-english (Accessed: 04.05.2022.)

- “France: Military spending, percent of GDP”. In: theglobaleconomy.com https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/France/mil_spend_gdp/ (Accessed: 12. 05. 2022.)

- KORPICS, Fanni: “Changing American Focus, can France turn this to its benefit?”. In: Danube Institute. 20. December 2021. https://danubeinstitute.hu/hu/kutatas/changing-american-focus-can-france-turn-this-to-its-benefit (Accessed: 10. 05. 2022.)

- “La Marine, Présente sur toutes les mers du monde”. In: Cols bleus. https://www.colsbleus.fr/ (Accessed: 04.05.2022.)

- LECOQ, Tristan: “La France et sa défense depuis la fin de la Guerre froide.Éléments de réflexions sur la réforme comme chantier permanent”. In: Outre-Terre 2012/3-4. 449-469.

- Ministère des Armées https://www.defense.gouv.fr/ (Accessed: 04.05.2022.)

- MOURA, Sylvain: “La R&D de défense en France: quels changements depuis la guerre froide?”. In: Revue de la regulation. 28/2nd semester, 2020 Autumn

- “Point sur le soutien apporté par la France à l'Ukraine et à la Moldavie”. In: Élysée.fr. 2 May 2022. https://www.elysee.fr/emmanuel-macron/2022/05/02/point-sur-le-soutien-apporte-par-la-france-a-lukraine-et-a-la-moldavie (Accessed: 10. 05. 2022.)

- ROSE, Michel – SHIRBON, Estelle: “’Very, very nasty’: Trump clashes with Macron before NATO summit”. In: Reuters, 3 December 2019. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-nato-summit-idUSKBN1Y7005 (Accessed: 10. 05. 2022.)

- “The North Atlantic Treaty” 4 April 1949, Washington

- TERTRAIS, Bruno – VERGERON, Nathalie: “OTAN: que veut la France?”. In: Diplomatie 2020/103. pp. 58-60.

- VAÏSSE, Maurice: “La France et L’OTAN: Une histoire”. In: Politique étrangères. 2009/4. 861-872.

Endnotes

[i] “Armed Forces Personnel, Total – France”. In: The World Bank. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.TOTL.P1?locations=FR (Accessed: 03.05.2022)

[ii] "Armed Forces Personnel”, Total – European Union. In: The World Bank https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.TOTL.P1?locations=EU (Accessed: 03.05.2022.)

[iii] “The North Atlantic Treaty” 4 April 1949, Washington

[iv] CHEVÈNEMENT, Jean-Pierre: “Le <<retour>> de la France dans l’OTAN: une decision inopportune”. In: Politique étrangère. 2009/4. 873-879.

[v] VAÏSSE, Maurice: “La France et L’OTAN: Une histoire”. In: Politique étrangères. 2009/4. 861-872.

[vi] LECOQ, Tristan: “La France et sa défense depuis la fin de la Guerre froide.Éléments de réflexions sur la réforme comme chantier permanent”. In: Outre-Terre 2012/3-4. 449-469.

[vii] “France: Military spending, percent of GDP”. In: theglobaleconomy.com https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/France/mil_spend_gdp/ (Accessed: 12. 05. 2022.)

[viii] MOURA, Sylvain: “La R&D de défense en France: quels changements depuis la guerre froide?”. In: Revue de la regulation. 28/2nd semester, 2020 Autumn

[ix] Ministère des Armées https://www.defense.gouv.fr/ (Accessed: 04.05.2022.)

[x] Ministère des Armées https://www.defense.gouv.fr/ (Accessed: 04.05.2022.)

[xi] “Armée de Terre”. In: Ministère des Armées. https://www.defense.gouv.fr/terre (Accessed: 04.05.2022.)

[xii] “Armée de Terre”. In: Ministère des Armées. https://www.defense.gouv.fr/terre (Accessed: 04.05.2022.)

[xiii] “La Marine, Présente sur toutes les mers du monde”. In: Cols bleus. https://www.colsbleus.fr/ (Accessed: 04.05.2022.)

[xiv] Défense/Avec vous (Presidential Programme of Emmanuel Macron 2022) https://avecvous.fr/notre-action/defense (Accessed: 10. 05. 2022.)

[xv] BONIFACE, Xavier: “Guerre en Ukraine: quell impact sur la politique de défense française?”. In: The Conversation. 18. April 2022. https://theconversation.com/guerre-en-ukraine-quel-impact-sur-la-politique-de-defense-francaise-181007 (Accessed: 10. 05. 2022.)

[xvi] KORPICS, Fanni: “Changing American Focus, can France turn this to its benefit?”. In: Danube Institute. 20. December 2021. https://danubeinstitute.hu/hu/kutatas/changing-american-focus-can-france-turn-this-to-its-benefit (Accessed: 10. 05. 2022.)

[xvii] ROSE, Michel – SHIRBON, Estelle: “’Very, very nasty’: Trump clashes with Macron before NATO summit”. In: Reuters, 3 December 2019. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-nato-summit-idUSKBN1Y7005 (Accessed: 10. 05. 2022.)

[xviii] “Emmanuel Macron in his own words” In: The Economist. 7 November 2019. https://www.economist.com/europe/2019/11/07/emmanuel-macron-in-his-own-words-english (Accessed: 04.05.2022.)

[xix] TERTRAIS, Bruno – VERGERON, Nathalie: “OTAN: que veut la France?”. In: Diplomatie 2020/103. pp. 58-60.

[xx] TERTRAIS, Bruno – VERGERON, Nathalie: “OTAN: que veut la France?”. In: Diplomatie 2020/103. pp. 58-60.

[xxi] BARON, Kevin: “It’s Macron’s Moment to Move Europe Beyond NATO”. In: Defense One. 25 January 2022. https://www.defenseone.com/ideas/2022/01/its-macrons-moment-move-europe-beyond-nato/361163/ (Accessed: 10. 05. 2022.)

[xxii] “Actudéfense” In: Ministère des Armées, 3 March, 2022.

[xxiii] “Point sur le soutien apporté par la France à l'Ukraine et à la Moldavie”. In: Élysée.fr. 2 May 2022. https://www.elysee.fr/emmanuel-macron/2022/05/02/point-sur-le-soutien-apporte-par-la-france-a-lukraine-et-a-la-moldavie (Accessed: 10. 05. 2022.)

[xxiv] CANTIÉ, Valérie: “Rester dans l’OTAN un peu, beaucoup, pas du tout: ce que proposent les candidats à la présidentielle” In: France Inter 5 April 2022. https://www.franceinter.fr/monde/rester-dans-l-otan-un-peu-beaucoup-pas-du-tout-ce-que-proposent-les-candidats-a-la-presidentielle (Accessed: 10. 05. 2022.)

[xxv] BONIFACE, Xavier: “Guerre en Ukraine: quell impact sur la politique de défense française?”. In: The Conversation. 18. April 2022. https://theconversation.com/guerre-en-ukraine-quel-impact-sur-la-politique-de-defense-francaise-181007 (Accessed: 10. 05. 2022.)