Research / Geopolitics

From Demilitarisation to Remilitarisation: the case of Germany

From Demilitarisation to Remilitarisation: the case of Germany

Virág Lőrincz

Abstract: After the Second World War the Allies were unanimous in the decision to abolish the former aggressor’s, Germany’s military power. However, during the Cold War, as the threat posed by the Soviet Union was intensifying, the need for the rearmament of West Germany emerged. In the second half of the 20thcentury, the two parts of the divided country followed different paths within the NATO and the Warsaw Pact. After the reunification of Germany, the new security situation led to a significant reduction of the renewed Bundeswehr. The changing security environment of recent years has put increasing pressure on German military development, and the ongoing war in Ukraine might usher in a new era in the Bundeswehr's history.

Keywords: Germany, demilitarisation, remilitarisation, Bundeswehr, security policy, military development, NATO

Germany’s guilt and responsibility for the atrocities committed during the Second World War shaped the country’s attitude toward militarisation. Although after the end of the war the remilitarisation of Germany was unthinkable, ten years later both parts of the divided country developed their own armies. After decades of reluctance to significantly increase defence spending, recent events mark the beginning of a new era in German security and defence policy; the robust development of the armed forces to even exceed the 2% of the GDP expenditure goal set by NATO was announced.

The aftermath of the Second World War

7 May 1945 marked the unconditional surrender of the German Third Reich, and the period that followed had such consequences for the country that still define its role in the international security environment. The Yalta and half a year later the Potsdam Conference resulted in a broad agreement between the Allied powers on the post-war administration of Germany, with particular regard to the military dimension.

Potsdam Conference

The post-war power balance was shaped at the Potsdam Conference, which had resulted in an agreement on 1 August 1945 between the “Big Three” (leaders of the United States, Great Britain, and the Soviet Union). Determining Germany’s fate was among the most important aims of the conference. The Potsdam Agreement included the plans for “the complete disarmament and demilitarization of Germany and the elimination or control of all German industry that could be used for military production.”[1] To achieve this, the agreement provided concrete measures, including the abolishment of all German land, naval and air forces, and the complete dissolution of every military and semi-military organisation, such as the Schutzstaffel (SS), Sturmabteilung (SA), Sicherheitsdienst (SD), and the Gestapo. Beside the final abolishment of these organisations, the production of all arms, ammunition, implements of war, machinery and other items that were directly connected to a war economy was prohibited. All these were intended to serve the purpose of preventing the revival and reorganisation of German militarism, and the measures taken were supervised by the occupying Allied powers.

Demilitarisation after 1945

The surrender of the German Third Reich came with a very heavy cost to the country's military power, as its demilitarisation was one of the most important goals of the occupying Allied powers in 1945.

The Allied Control Council for Germany was established in August 1945, aiming to exercise thorough joint authority over all four (American, British, French, and Soviet) occupation zones.[2] Although the Allied Control Council proclaimed the disbanding of all military formation, German police units were permitted to operate in all four zones and by the establishment of the East and West German states in 1949, many among the new border guards were former Wehrmacht soldiers.[3]

It was the “Operation Eclipse”, elaborated by Supreme Headquarters and Allied Expeditionary Forces (SHAEF) that made detailed provisions on the occupation of Germany. Five from the seventeen documents of the Eclipse Memoranda[4] dealt directly with the elements of the disbandment of the German Armed Forces, such as the disarmament and demobilisation of each military service (land, air, and naval forces), and the policies, by which it had to be managed.

As the three zones, which were occupied by the United States, Great Britain and France merged in 1949, the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG, also known as West Germany) was created, and at the same time the Soviet Union declared the statehood of the fourth and Soviet zone named as the German Democratic Republic (GDR, also known as East Germany). Both newly established constitutions, the Basic Law of the Federal Republic of Germany (Grundgesetz)[5] and the constitution of the GDR[6] included restrictions on the use of force. However, as the international security environment had gone under significant changes, in the advent of the Cold War the need for the remilitarisation of the two Germanys emerged on both sides.

Remilitarisation of the divided Germany

The fact that the two parts of the divided Germany belonged to different spheres of interest meant that the two Germanys were developing within opposing military alliances during the Cold War. In 1955 the Federal Republic of Germany became member of the NATO and in the same year the German Democratic Republic was among the founding members of the Warsaw Pact.

Federal Republic of Germany

The Allies’ plan on the total demilitarisation of Germany stemmed from the failures of the post-First World War attempt to control German disarmament. However, being on the frontline of the rivalry between the capitalist West and the communist East did not allow either part of the divided Germany to remain disarmed. Occupied by the Western Allies, the remilitarisation of the FRG seemed unavoidable to counterbalance the Soviet military build-up, which led to its NATO membership.

Years of ambiguity (1948-1950)

The increasing hostility between the Soviet Union and the United States and the advent of the Cold War led to the slow transformation of the US policy toward Western Europe, with a particular regard to the FRG, by early 1949. As a consequence of the unexpected outbreak of the Korean War on 25 June 1950 it resulted in a total reverse of the US’s West German policy, and the remilitarisation of the former aggressor state was put on the agenda, Besides the increasing international tensions, two other circumstances allowed the rearmament of the FRG: the lack of a European war and the division of Germany.[7]

The benefits of the European Recovery Program between 1948 and 1952 allowed West Germany to improve its economic and industrial capabilities. Since the establishment of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) on 4 April 1949, the question regarding the inclusion of the FRG in the alliance had often been raised, and the late 1940s were characterised by rumours about German rearmament and an atmosphere of ambiguity. Although the possible remilitarisation of the FRG and thus, its tighter integration to the West was among the “hottest issues” that time, the fear from German militarism remained a determining factor, especially from the French perspective, which aimed at keeping Germany down and at avoiding a possible unification of the former aggressor in its neighbourhood.[8]

With the support of the occupying Allies, the first FRG elections in 1949 resulted in the appointment of Konrad Adenauer as the first chancellor. He favoured the policy of rearmament in response to the increasing Soviet threat, as he wanted Germany to contribute to the defence of Europe. In his memorandum on security in August 1950, he expressed his concerns about the inefficient security forces in Western Germany and proposed concrete recommendations, including the possible amendments of the Grundgesetz.[9]

Towards NATO (1950-1955)

A few weeks after the outbreak of the Korean War in June 1950, the urgent need for the rearmament of the FRG emerged. The threat posed by the Soviet Union was increasing as it had acquired nuclear capability in 1949. Moreover, numerous European NATO members had their armies deployed abroad, for instance the French army was in Indochina and the British units were stationed in Malaysia. In the geographical heart of the Western-Eastern hostility, the FRG was without army, Ministry of Defence or Ministry of Foreign Affairs. By this time, almost all members of NATO supported the idea of German rearmament, except for France and Belgium, where memories of the German occupation were still too vivid.[10]

As it became clear, that an effective European defence cannot be achieved without German contribution, the rearmament of the FRG was openly discussed for the first time in September 1950, at the Foreign Ministers’ Conference in New York. The discussion went on later in that year, within the context of the Pleven Plan on the European Defence Community (EDC), where the German rearmament was imagined within the context of a European army under a supranational defence minister, instead of the establishment of a German national army. The ratification of the agreement on the EDC failed in the French National Assembly in 1954, and instead the establishment of the Western European Union (WEU) provided a feeble substitute as a “second option”, in the same year. Although it did not set up a European army, it authorised the German rearmament, ended the occupation of Western Germany, and permitted the country’s preparation for defence contribution.[11]

This way, the West German rearmament could happen under the control of a European organisation, under an integrated command of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), instead of its direct accession to NATO. After that the FRG was enabled to develop its national army, the Bundeswehr (Federal Defence Force), it could join the NATO one year later 6 May 1955.

The establishment of the Bundeswehr

The Bundeswehr was in fact established on 12 November 1955, when the first 101 enlisted volunteers got their appointment letters, and it was integrated into the NATO structure from the beginning. The first measures included the introduction of the Compulsory Military Service Act in 1956[12], which remained in force until 2011, and the Basic Law was amended to contain the defensive characteristic of the newly formed army.[13]The rapid armament of West Germany relied heavily on the “economic miracle” of the 1950s, triggered by the European Recovery Program (Marshall Plan).

Aligned with NATO

During the Cold War, because of being in the front line in the middle of Europe, the FRG became the backbone of NATO’s defence and had the densest concentration of military forces on its territory in the era of multinational exercises. The threat heightened as the Berlin Wall was built and the strength and equipment of the Bundeswehr had to be improved. By engaging in the strategy of “forward defence” the German defence forces were placed as far to the east as possible, reaching the demarcation line of the Iron Curtain by 1963. The Western defence line meant an incredible concentration of military power, including hundreds of thousands of troops, commands, headquarters, weapon systems and equipment storage facilities. In addition to their own contribution with the German land, naval, and air forces, massive American support in terms of troops and defence funds was also provided. The German Army was provided with weapons and other military equipment by the US, such as M-47 (later M-48) tanks, but smaller arms and uniforms were produced by Germany itself. As for manpower, the initial plans authorised 310,000 troops, however, as the nuclear and conventional threat posed by the Soviet Union increased in the 1950s and 1960s, this number increased to some 415,000 by 1964.[14]

The mid-1970s brought a need for modernisation as the Soviet Union advanced its position in medium and intermediate range nuclear ballistic missiles. As a response, NATO adopted the Double-Track Decision, which meant the modernisation of its nuclear weapons in Europe but, at the same time, they also started to seek negotiation with the Soviet Union about arms control. This wave of development affected the German army, as numerous new technologies were developed, including anti-tank guided missiles, Leopard 2 tanks and new weapon systems.[15]

German Democratic Republic

Under the rule of the Soviet Union, the GDR went under a similar process as West Germany in many aspects. The National People’s Army (National Volksarmee, NVA) was formally founded in 1956, and was fully integrated into the Soviet military structure, which exercised control over the German armed forces. From the beginning of the Soviet occupation, a native German police force had been operating. Military equipment and training were provided for them and later they gave the framework of the NVA’s personnel. In contrast to the Bundeswehr’s recruitment system, the social instability and distrust in the occupying power did not allow the direct implementation of conscription until 1962, the year after the Berlin Wall was built.[16]

In response to the accession of West Germany to NATO, the Warsaw Pact was created in 1955 by the Soviet Union and its satellite states, including the GDR. At the end of the Second World War, the six divisions of the GDR meant to be the largest and best-equipped combat-ready force of the Soviet Union’s non-Soviet Warsaw Pact divisions, and it was officially known as the Soviet Occupation Force in Germany Group with approximately 500,000 personnel. Although in numbers the Polish, Czechoslovak and Hungarian militaries had bigger ground forces in relative terms, they did not catch up in terms of combat readiness and equipment.[17]

The military expenditures of the GDR had been increasing steadily from the 1960s, especially compared to the Polish and Czechoslovak contribution, which were stagnating at that time. The Soviet Union did not support the reconstruction of the GDR’s military industry due to historical reasons until the 1960s, thus German arms trade with Czechoslovakia, Poland and the Soviet Union was of utmost importance.[18] The NVA was considered to be a significant and very efficient contributor to the Warsaw Pact’s military power, although compared to the Western German army its outmoded equipment meant a relative weakness.

Reunification

With the reunification of the two Germanys on 3 October 1990 the NPA and other East German armed forces, such as the border troops were disbanded. Although some of them entered the Bundeswehr (approximately 90,000 people), they had to cope not only with the discrepancies stemming from the different training experiences and technical equipment they used, but also with the often-hostile attitude of the Bundeswehr personnel towards former NPA soldiers. Besides, as the Cold War ended, there was no need for maintaining the same military power, so the downsizing of the Bundeswehr began.

The German unification was established by the Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany[19], signed in 1990. It required the reduction of the personnel of the united Germany’s armed forces to 370,000 and then to 345,000 by 1994, when the last Soviet troops were to be withdrawn from German territories.

As the NPA’s military equipment was to be disbanded as well, more than 15,000 large weapon systems, and 300,000 tonnes of ammunition had to be destroyed. Although some pieces of equipment were allowed to be temporarily used by the Bundeswehr, such as the MiG 29 combat aircrafts until 2004, but these were exceptional cases. Some members of NATO bought military vehicles and attack helicopters from the disposed NPA’s inventory.[20]

The military evolution of Germany after 1990 was determined by various circumstances, such as the end of the Cold War, the change of the nature of warfare and the strengthening of the European integration from economic, political, and military aspects alike. In the new security environment, the position of the united Germany had changed dramatically. The lack of serious external threat urged the need to rethink the future tasks of the country’s armed forces.

Post-Cold War era

The post-Cold War era meant a shift towards the unified, secure, and peaceful Europe. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the lack of existential threats resulted in a streak of pacifism in Germany after having been a military borderland during the Cold War. While undergoing a significant reconstruction, the Bundeswehr had to face the first period of its downsizing. This trend can be observed through the changes in the country’s military spending and the decline in the number of military personnel.

Military expenditure

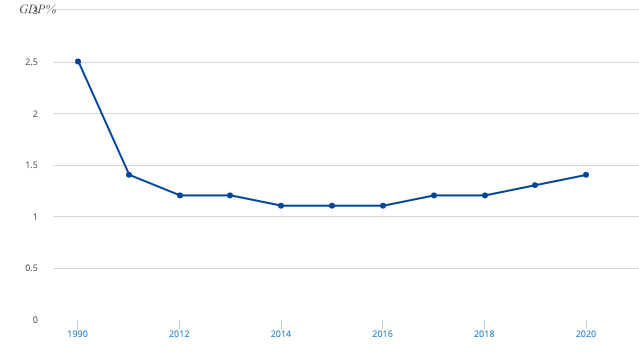

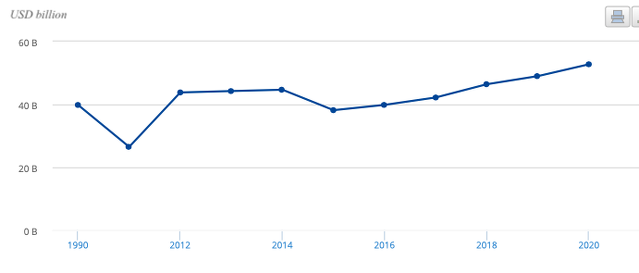

A turning point in German military expenditure happened with the end of the Cold War. Previously, the defence spending was relatively high, in West Germany it meant 2.4% of the GDP in 1989. The changed security environment lacked any imminent threat, and in the reunified Germany the defence budget shrank dramatically. The next fundamental change happened in 2011 by suspending the compulsory military service and reducing the number of personnel. Crisis management operation scenarios served as the basis for military planning, this way the army was considered to be fully equipped

using only 70% of existing military materiel.[21] The defence budget compared to the country’s GDP has been stagnating since the beginning of the post-Cold War era (Figure 1), however, given the economic development of recent years, this percentage of GDP represents an increasing amount of money (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Military expenditure (% of GDP) of Germany between 1990 and 2020. Source: World Bank[22]

Figure 2: Military expenditure (current USD) of Germany between 1990 and 2020. Source: World Bank[23]

Military personnel

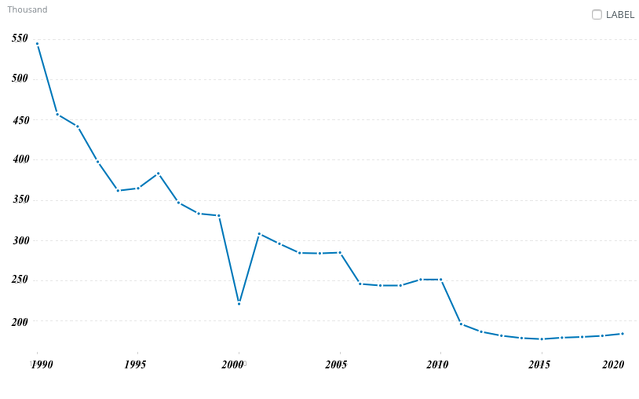

Regarding the number of military personnel, a similar trend could be observed, which is illustrated by Figure 3. In 1990, the reunification of Germany resulted in a rapid growth of the Bundeswehr to more than 500,000 personnel. In the light of the reunification agreements, the number of military personnel was being reduced throughout the early 2000s and this trend went on until recently; in 2021, the total military personnel counted 199,000 people.[24] It was the result of a planned reduction of the Bundeswehr in 2011, when compulsory military service was suspended. As the primary goal of the army shifted towards the need for small expeditionary forces, it was more adequate to have a smaller, professional military instead of a larger conscripted one. The focus of the renewed Bundeswehr was put on the military actions within the framework of United Nations or NATO operations.

Figure 3: Total number of armed forces personnel in Germany between 1990 and 2020. Source: World Bank[25]

The renewed Bundeswehr

Established in 1990, the renewed Bundeswehr is characterised by the principal of “alliance loyalty” (Bundnistreue), referring to the German commitment to act as a part of the various alliances, including NATO, the European Union, the United Nations, and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). Until the reunification, the Bundeswehr’s mission was national and collective defence, and to back up its defensive nature, it only participated in international peacekeeping and not in combat missions up until the NATO airborne attacks in Yugoslavia.

The first modern combat mission of the Bundeswehr was its participation in the NATO air strikes against Serbian targets during the war in Kosovo by the Luftwaffe’s intervention in 1999. Consequently, the NATO peacekeeping troops, KFOR (Kosovo Force) started to operate with German command for several years. By providing support for stabilising the peace and coordinating humanitarian relief, Germany extended its presence until the end of June 2022, with the limitation that only 400 soldiers can participate.[26] Currently, approximately 2,700 German soldiers are participating in international operations on three continents, the contribution to the UN-led MINUSMA mission in Mali is the most significant with more than 1,000 soldiers.[27]

Consequences of the Crimea crisis

The Russian annexation of the Crimean Peninsula resulted in a shift of the German military strategy. NATO’s new strategic direction of territorial defence and deterrence determined its member states’ policies as well. Germany focused on national and collective defence, but in the meantime, it contributed to international crisis management operations, like in Afghanistan and in Kosovo, challenging the country’s capacity. Aligned with NATO, the German Army became a framework nation of the Enhanced Forward Presence on NATO’s eastern flank by commanding one of the four battalion-size battlegroups in Lithuania, and the rapid response force of NATO, the Very High Readiness Joint Task Force.[28]

On the occasion of the NATO Wales Summit in 2014 after the Russian annexation of Crimea, the member states committed themselves to increasing their defence budgets to the requirement of the 2% of their respective GDPs. Despite the constant pressure from its allies, particularly from the Trump administration, Germany’s defence expenditure remained almost stagnating during the post-Cold War era and was around 1.5% of the GDP in 2021 (see Figure 1).

Developing arms industry

The German economy is among the strongest ones in the world, it is the fourth strongest globally in terms of nominal GDP (after the US, China, and Japan) and the leading economic power in Europe.[29] Despite being often criticized for under-investing in its army’s equipment and for the incompetency of the procurement system, Germany belongs to the world’s largest exporters of major arms. German arms export gave 5.5% of the total global arms exports between 2016 and 2020, thereby being the second largest exporter in Europe after France.[30]

Data provided by Germany’s Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Action show that the value of the country’s arms export reached a record high in 2021, 61% up on 2020. Although Germany exports arms to EU countries, NATO partners and NATO-equivalent-status countries in a significant value, an even more tremendous volume of weapons went to third countries in addition to the above, such as Egypt and Singapore.[31]

The issue of arms export is very controversial in Germany, and it essentially divides political parties and public opinion since the establishment of the West German defence industry in the 1960s. The federal governments are basically committed to a more limited arms export policy, including that military companies are only allowed to export assault weapons to NATO and EU member states, and only in exceptional cases outside of Europe, though in reality these principles are often violated. Haunted to this day by its fraught 20th-century history, German arms industry receives widespread social rejection and is in the centre of domestic political debates as well.[32]

Military strategy – the future of the Bundeswehr

The most recent military strategy of Germany is detailed in the White Paper published in 2016. Defining the mission, guiding principles, and the capabilities of the Bundeswehr, the document highlights the priority of defending Germany’s sovereignty and territorial integrity and protecting its citizens.[33]

The new white paper set such limited boundaries and ambitious goals for the Bundeswehr that they projected a new step in the revival of German militarism. Besides permitting the army’s domestic deployment, it also provided for the massive build-up of the Bundeswehr and referred to Germany as a key player in Europe, which should take more responsibility and leadership on the continent.

Relations with the United States

Being the largest military and financial contributor of NATO, the US plays a significant role in shaping the policies of the alliance and therefore the nature of the relationship with it is decisive. The German-US military relationship and cooperation has for many years been shaped within the framework of NATO. The two countries’ militaries have been working closely together for a long time, and the German contribution to foreign operations had been recognised several times, such as its leading role as a framework nation in North Afghanistan.

US military presence in Germany

From a geostrategic point of view, Germany served as an important military base for US troops for a long time. Since the end of the Second World War, the US military presence is a legacy of the post-war Allied occupation. Although its presence had declined since then, Germany is still of strategic importance to the US.

By currently stationing roughly 35,000 troops in Germany, which is by far the largest number among European countries, the US contributes to the continent’s security. The US presence is not limited to personnel, but Germany also hosts several major military facilities, such as the US European Command (EUCOM) headquarters, which serves as a coordinating centre for the US posture in the European theatre, the Ramstein Air Base, the headquarter of the US Africa Command, and it is also stationing planes at non-US air force bases in Germany. Nuclear weapons are also believed to be kept in the country.[34]

Tensions between Washington and Berlin

Germany’s post-war pacifism was bland for its neighbours and allies once, but this is not the situation any more in the changing security environment of the 21st century. Although the Merkel-cabinets sometimes had come into conflict with former US administrations, the tensions reached a peak during the Trump presidency.

Back to 2018, the strong statements of Donald Trump got viral attention. Following the Brussels Summit of NATO, he confronted the European allies and Canada criticising their insufficient defence budgets, with no prospects of achieving the 2% of their GDPs in the near future. He even threatened with the withdrawal of some US troops from Germany, after repeatedly accusing Germany with being “delinquent” for failing to spend 2% of its GDP on defence. Another critical issue was the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline and the relatively good German-Russian relations, which were condemned by the then-US president.[35]

Although Biden's presidency has led to improved relations between the two countries, they are also the result of significant changes in German foreign and security policy. Assessing the difference between Merkel's cabinet and Olaf Scholz's government, it is clear that the issues Trump used to be tough on Germany has fixed by now as a consequence of the Russian-Ukrainian war. Germany, along with its western allies, condemned the Russian aggression and imposed a number of sanctions against the country, including the suspension of Nord Stream 2 and announced a major arms project, aiming to exceeding the 2% of GDP NATO goal. It does not mean that there are no tension or disagreement between the two countries, especially regarding China, but the defence cooperation has improved.

Current events – war in Ukraine

Three days after the Russian invasion in Ukraine had begun, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz announced that Germany would increase its defence spending to more than 2% of the GDP, exceeding the NATO goal, and would set up a 100-billion-euro defence fund for military investments in 2022. This will require an annual 3-4-billion-euro increase in defence spending. The serosity of the changed security perception of Germany is also manifested in the halt of the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline project with Russia. At least as significant is the decision on Germany being allowed to send weapons to Ukraine, after a long time of refusing to send military equipment to conflict zones and opposing that third-country buyers of German equipment re-export the weapons to warzone areas.[36]

Russian aggression in Ukraine seems to have brought the breaking point in German military development that neither Donald Trump's nor NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg's call was enough to achieve; to spend more on defence. However, Germany is not alone in increasing its defence budget: since the Russian invasion of Ukraine started six other European nations have announced similar aspirations (Belgium, Romania, Italy, Poland, Norway, and Sweden).[37]

Since the outbreak of the Russian-Ukrainian war, various new acquisitions had been announced in the context of Germany’s defence strategy adjustment, including the planned purchase of new F-35 fighter jets, suitable for nuclear deterrence, the constant ambitions regarding the development of a common European fighter jet together with France and Spain.[38] There are possible options about Israeli acquisitions, such as the Arrow 3 anti-missile shield system and armed drones.[39] The promises, however, about increasing defence budget and the acquisitions have to be fulfilled in a wise way, as Germany was previously criticized not only for under-funded militarisation but also for the poor management of defence procurement.

An important aspect to examine is the society’s attitude towards the robust military development of Germany. As new generations are growing up and the dark memories of German militarism are fading, the popular support for military development is increasing. A recent poll showed that 69% of the voters support the idea to boost military spending to the 2% of the GDP[40] compared to the 35% result of the same poll in 2018.[41] It seems like the Russian invasion of Ukraine has brought a shift in the public opinion as well.

Conclusions

The post-Second World War demilitarization of Germany did not last long, as under the increasing tensions of the bipolar international system, with the West and East Germanys being in the frontline became prioritised. Determined by the negative memories in connection to German militarism, the post-Cold War era meant a shift towards pacifism. However, the new challenges of the 21st century resulted in a changed security environment, in which, it was the German passivity towards militarisation that posed more of a danger. The pressure on European countries to be able to defend themselves and not to rely so heavily on America is increasing.

In the light of the current Russian-Ukrainian war, the German policy of keeping a low military profile in part because of the guilt over the Second World War has taken a huge turn. Vows have been made; it is the task of Germany’s new chancellor to realise the major reverse that has been promised.

In conclusion, the idea is laudable, the expectations have been set high, and the implementation will require a huge effort, but preliminary calculations[42] suggest that it would put Germany among the world's top three defence budget spenders behind the United States and China.

Bibliography

2022 Germany Military Strength. In: Global Firepower, 05. 02. 2022, https://www.globalfirepower.com/country-military-strength-detail.php?country_id=germany (22. 05. 2022.)

Allied Control Councils and Commissions. In: International Organization, Vol. 1. No. 1. (Feb., 1947) pp. 162-170.

Allied Forces Supreme Headquarters Operation Eclipse Appreciation and Outline Plan. https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/ETO/Surrender/ECLIPSE/index.html (21. 05. 2022.)

ARD-DeutschlandTREND Marz 2022. In: Tagesschau, Marz 2022, https://www.tagesschau.de/dtrend-747.pdf (25. 05. 2022.)

Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany. In: Federal Ministry of Justice. https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/englisch_gg/englisch_gg.html#p0030 (21. 05. 2022.)

BRZOSKA, Michael: Debating the future of the German arms industry, again. In: SIPRI, 07. 11. 2014, https://www.sipri.org/commentary/blog/2014/debating-future-german-arms-industry-again (22. 05. 2022.)

Bundeswehr to continue engagement in Kosovo. In: The Federal Government. 12. 05. 2021, https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-en/news/extension-kfor-1913782 (22. 05. 2022.)

Constitution of the German Democratic Republic (7 October 1949). In: CVCE.eu, 03. 07. 2015, https://www.cvce.eu/content/publication/1999/1/1/33cc8de2-3cff-4102-b524-c1648172a838/publishable_en.pdf (21. 05. 2022.)

CRANE, Keith: East Germany’s Military: Forces and Expenditures. California, RAND Corporation, 1989.

DAUGHERTY, Leo J.: Tip of the Spear: The formation and expansion of the Bundeswehr, 1949-1963. In: Journal of Slavic Military Studies, Vol. 24, Issue 1, January-March 2011, https://omnilogos.com/tip-of-spear-formation-and-expansion-of-bundeswehr-1949-1963/ (21. 05. 2022.)

Deutsche sind klar gegen Erhöhung von Militarausgaben. In: Welt, 11. 07. 2018, https://www.welt.de/politik/deutschland/article179144290/Umfrage-Deutsche-sind-klar-gegen-Erhoehung-von-Militaerausgaben.html (25. 05. 2022.)

GDP Ranked by Country 2022. In: World Population Review, https://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/countries-by-gdp (22. 05. 2022.)

German weapons exports hit record with bumper Egypt sales. In: DW, https://www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/DE/Pressemitteilungen/2022/01/20220118-ruestungsexportpolitik-der-bundesregierung-im-jahr-2021-vorlaeufige-genehmigungszahlen.html (28. 06. 2022.)

Gesetz zur Erganzung des Grundgesetzes. In: Bundesgesetzblatt Teil I, Nr. 11 vom 21. 03. 1956, https://www.bgbl.de/xaver/bgbl/start.xav?startbk=Bundesanzeiger_BGBl&jumpTo=bgbl156s0111.pdf#__bgbl__%2F%2F*%5B%40attr_id%3D%27bgbl156s0111.pdf%27%5D__1653512655612(21. 05. 2022.)

How Germany, shaken by Ukraine, plans to rebuild its military. In: France24, 29. 03. 2022, https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20220329-how-germany-shaken-by-ukraine-plans-to-rebuild-its-military (25. 05. 2022.)

JONES, Timothy: US threatens to withdraw troops from Germany. In: DW, 09. 08. 2019, https://www.dw.com/en/us-threatens-to-withdraw-troops-from-germany/a-49959555 (22. 05. 2022.)

KINGHT, Ben: US military in Germany: What you need to know. In: DW, 16. 06. 2020, https://www.dw.com/en/us-military-in-germany-what-you-need-to-know/a-49998340 (22. 05. 2022.)

KUNZ, Barbara: The real roots of Germany’s defense spending problem. In: War on the Rocks, 24. 06. 2018, https://warontherocks.com/2018/07/the-real-roots-of-germanys-defense-spending-problem/ (21. 05. 2022.)

MACKENZIE, Christina: Seven European nations have increased defense budgets in one month. Who will be next? In: Breaking Defense, 22. 03. 2022, https://breakingdefense.com/2022/03/seven-european-nations-have-increased-defense-budgets-in-one-month-who-will-be-next/ (25. 05. 2022.)

MARKSTEINER, Alexandra: Explainer: The proposed hike in German military spending. In: SIPRI, 25. 03. 2022, https://www.sipri.org/commentary/blog/2022/explainer-proposed-hike-german-military-spending (25. 05. 2022.)

MARSH, Sarah: Germany to increase defence spending in response to ’Putin’s war’ – Scholz. In: Reuters, 27. 02. 2022, https://www.reuters.com/business/aerospace-defense/germany-hike-defense-spending-scholz-says-further-policy-shift-2022-02-27/ (22. 05. 2022.)

Memorandum von Konrad Adenauer über die Sicherung des Bundesgebietes (29 August 1950). In: CVCE., 14. 05. 2013, https://www.cvce.eu/en/obj/memorandum_from_konrad_adenauer_on_security_in_the_frg_29_august_1950-en-77999062-f79e-41d9-9906-66cb5afb99e3.html (21. 05. 2022.)

Modified Brussels Treaty (Paris, 23 October 1954). In: CVCE. 25. 10. 2016, https://www.cvce.eu/en/obj/modified_brussels_treaty_paris_23_october_1954-en-7d182408-0ff6-432e-b793-0d1065ebe695.html (21. 05. 2022.)

Number of German soldiers participating in international operations, as of January 31, 2022. In: Statista. 21. 02. 2022, https://www.statista.com/statistics/265883/number-of-soldiers-of-the-bundeswehr-abroad/(22. 05. 2022.)

Potsdam Agreement. https://www.nato.int/ebookshop/video/declassified/doc_files/Potsdam%20Agreement.pdf (21. 05. 2022.)

SPRENGER, Sebastian: Germany to buy F-35 warplanes for nuclear deterrence. In: Defense News, 14. 03. 2022, https://www.defensenews.com/global/europe/2022/03/14/germany-to-buy-f-35-warplanes-for-nuclear-deterrence/ (25. 05. 2022.)

STEIRNS, Peter N.: Demilitarization in the Contemporary World. Chicago, University of Illnois Press, 2013.

The Bundeswehr becomes an „army of unity”. In: Bundeswehr, https://www.bundeswehr.de/en/about-bundeswehr/history/army-of-unity-german-reunification (21. 05. 2022.)

The history of the German army. In: Bundeswehr, https://www.bundeswehr.de/en/about-bundeswehr/history/history-german-army (21. 05. 2022.)

The need for German rearmament. In: CVCE., 07. 07. 2016, https://www.cvce.eu/collections/unit-content/-/unit/en/df06517b-babc-451d-baf6-a2d4b19c1c88/89fc42e3-4895-476c-9cea-62173abf0bfd/Resources#be64df30-92d8-4e3c-bd97-d870e3d6a121_en&overlay (21. 05. 2022.)

Treaty on the final settlement with respect to Germany. In: United Nations – Treaty Series, October 1992, https://treaties.un.org/doc/Publication/UNTS/Volume%201696/volume-1696-I-29226-English.pdf (21. 05. 2022.)

Wehrpflichtgesetz. In: Bundesministerium der Justiz. http://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/wehrpflg/index.html(21. 05. 2022.)

WEZEMAN, Peter D. – KUIMOVA, Alexandra – Wezeman, Siemon T.: Trends in International Arms Transfers, 2020. In: SIPRI Fact Sheet, March 2021, https://sipri.org/sites/default/files/2021-03/fs_2103_at_2020.pdf (22. 05. 2022.)

White Paper on German Security Policy and the Future of the Bundeswehr. In: The Federal Government, 2016, https://issat.dcaf.ch/download/111704/2027268/2016%20White%20Paper.pdf (22. 05. 2022.)

Endnotes

[1] Potsdam Agreement. https://www.nato.int/ebookshop/video/declassified/doc_files/Potsdam%20Agreement.pdf (21. 05. 2022.)

[2] Allied Control Councils and Commissions. In: International Organization, Vol. 1. No. 1. (Feb., 1947) pp. 162-170.

[3] STEIRNS, Peter N.: Demilitarization in the Contemporary World. Chicago, University of Illnois Press, 2013.

[4] Allied Forces Supreme Headquarters Operation Eclipse Appreciation and Outline Plan. https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/ETO/Surrender/ECLIPSE/index.html (21. 05. 2022.)

[5] Constitution of the German Democratic Republic (7 October 1949). In: CVCE.eu, 03. 07. 2015, https://www.cvce.eu/content/publication/1999/1/1/33cc8de2-3cff-4102-b524-c1648172a838/publishable_en.pdf (21. 05. 2022.)

[6] Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany. In: Federal Ministry of Justice. https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/englisch_gg/englisch_gg.html#p0030 (21. 05. 2022.)

[7] STEIRNS, Peter N.: Demilitarization in the Contemporary World. Chicago, University of Illnois Press, 2013.

[8] STEIRNS, Peter N.: Demilitarization in the Contemporary World. Chicago, University of Illnois Press, 2013.

[9] Memorandum von Konrad Adenauer über die Sicherung des Bundesgebietes (29 August 1950). In: CVCE., 14. 05. 2013, https://www.cvce.eu/en/obj/memorandum_from_konrad_adenauer_on_security_in_the_frg_29_august_1950-en-77999062-f79e-41d9-9906-66cb5afb99e3.html (21. 05. 2022.)

[10] The need for German rearmament. In: CVCE., 07. 07. 2016, https://www.cvce.eu/collections/unit-content/-/unit/en/df06517b-babc-451d-baf6-a2d4b19c1c88/89fc42e3-4895-476c-9cea-62173abf0bfd/Resources#be64df30-92d8-4e3c-bd97-d870e3d6a121_en&overlay(21. 05. 2022.)

[11] Modified Brussels Treaty (Paris, 23 October 1954). In: CVCE. 25. 10. 2016, https://www.cvce.eu/en/obj/modified_brussels_treaty_paris_23_october_1954-en-7d182408-0ff6-432e-b793-0d1065ebe695.html (21. 05. 2022.)

[12] Wehrpflichtgesetz. In: Bundesministerium der Justiz. http://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/wehrpflg/index.html (21. 05. 2022.)

[13] Gesetz zur Erganzung des Grundgesetzes. In: Bundesgesetzblatt Teil I, Nr. 11 vom 21. 03. 1956, https://www.bgbl.de/xaver/bgbl/start.xav?startbk=Bundesanzeiger_BGBl&jumpTo=bgbl156s0111.pdf#__bgbl__%2F%2F*%5B%40attr_id%3D%27bgbl156s0111.pdf%27%5D__1653512655612(21. 05. 2022.)

[14] DAUGHERTY, Leo J.: Tip of the Spear: The formation and expansion of the Bundeswehr, 1949-1963. In: Journal of Slavic Military Studies, Vol. 24, Issue 1, January-March 2011, https://omnilogos.com/tip-of-spear-formation-and-expansion-of-bundeswehr-1949-1963/(21. 05. 2022.)

[15] The history of the German army. In: Bundeswehr, https://www.bundeswehr.de/en/about-bundeswehr/history/history-german-army(21. 05. 2022.)

[16] STEIRNS, Peter N.: Demilitarization in the Contemporary World. Chicago, University of Illnois Press, 2013.

[17] STEIRNS, Peter N.: Demilitarization in the Contemporary World. Chicago, University of Illnois Press, 2013.

[18] CRANE, Keith: East Germany’s Military: Forces and Expenditures. California, RAND Corporation, 1989.

[19] Treaty on the final settlement with respect to Germany. In: United Nations – Treaty Series, October 1992, https://treaties.un.org/doc/Publication/UNTS/Volume%201696/volume-1696-I-29226-English.pdf (21. 05. 2022.)

[20] The Bundeswehr becomes an „army of unity”. In: Bundeswehr, https://www.bundeswehr.de/en/about-bundeswehr/history/army-of-unity-german-reunification (21. 05. 2022.)

[21] KUNZ, Barbara: The real roots of Germany’s defense spending problem. In: War on the Rocks, 24. 06. 2018, https://warontherocks.com/2018/07/the-real-roots-of-germanys-defense-spending-problem/ (21. 05. 2022.)

[22] Military expenditure (% of GDP) of Germany between 1990 and 2020. In: World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.XPND.GD.ZS?end=2020&locations=DE&start=1990 (29. 06. 2022.)

[23] Military expenditure (current USD) of Germany between 1990 and 2020. In: World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.XPND.CD?end=2020&locations=DE&start=1990 (29. 06. 2022.)

[24] 2022 Germany Military Strength. In: Global Firepower, 05. 02. 2022, https://www.globalfirepower.com/country-military-strength-detail.php?country_id=germany (22. 05. 2022.)

[25] Total number of armed forces personnel in Germany between 1990 and 2020. In: World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.TOTL.P1?end=2020&locations=DE&start=1990 (29. 06. 2022.)

[26] Bundeswehr to continue engagement in Kosovo. In: The Federal Government. 12. 05. 2021, https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-en/news/extension-kfor-1913782 (22. 05. 2022.)

[27] Number of German soldiers participating in international operations, as of January 31, 2022. In: Statista. 21. 02. 2022, https://www.statista.com/statistics/265883/number-of-soldiers-of-the-bundeswehr-abroad/ (22. 05. 2022.)

[28] The history of the German army. In: Bundeswehr, https://www.bundeswehr.de/en/about-bundeswehr/history/history-german-army(22. 05. 2022.)

[29] GDP Ranked by Country 2022. In: World Population Review, https://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/countries-by-gdp (22. 05. 2022.)

[30] WEZEMAN, Peter D. – KUIMOVA, Alexandra – Wezeman, Siemon T.: Trends in International Arms Transfers, 2020. In: SIPRI Fact Sheet, March 2021, https://sipri.org/sites/default/files/2021-03/fs_2103_at_2020.pdf (22. 05. 2022.)

[31] German weapons exports hit record with bumper Egypt sales. In: DW, https://www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/DE/Pressemitteilungen/2022/01/20220118-ruestungsexportpolitik-der-bundesregierung-im-jahr-2021-vorlaeufige-genehmigungszahlen.html (28. 06. 2022.)

[32] BRZOSKA, Michael: Debating the future of the German arms industry, again. In: SIPRI, 07. 11. 2014, https://www.sipri.org/commentary/blog/2014/debating-future-german-arms-industry-again (22. 05. 2022.)

[33] White Paper on German Security Policy and the Future of the Bundeswehr. In: The Federal Government, 2016, https://issat.dcaf.ch/download/111704/2027268/2016%20White%20Paper.pdf (22. 05. 2022.)

[34] KINGHT, Ben: US military in Germany: What you need to know. In: DW, 16. 06. 2020, https://www.dw.com/en/us-military-in-germany-what-you-need-to-know/a-49998340 (22. 05. 2022.)

[35] JONES, Timothy: US threatens to withdraw troops from Germany. In: DW, 09. 08. 2019, https://www.dw.com/en/us-threatens-to-withdraw-troops-from-germany/a-49959555 (22. 05. 2022.)

[36] MARSH, Sarah: Germany to increase defence spending in response to ’Putin’s war’ – Scholz. In: Reuters, 27. 02. 2022, https://www.reuters.com/business/aerospace-defense/germany-hike-defense-spending-scholz-says-further-policy-shift-2022-02-27/ (22. 05. 2022.)

[37] MACKENZI