Research / Geopolitics

Military development in the post-communist Poland

Military development in the post-communist Poland

Virág Lőrincz

The modernisation of the Polish Armed Forces entered a new phase after Poland acceded to NATO in 1999. After the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact, the Polish armed forces underwent a major downsizing and had to reduce their capabilities. They needed proper military equipment to ensure better cooperation and interoperability with the allied forces. As result, in more than 20 years of Poland’s NATO membership, it’s armed forces have grown into one of the organisation's strongest militaries and the country is one of the few to meet the 2% of the GDP military budget ambition level. The study highlights key milestones in developing Polish military equipment and reflects on recent events.

Keywords: Poland, military equipment, NATO, Polish Armed Forces, modernisation

Before the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Polish army included more than 350,000 soldiers and was rather offensive than defensive. Maintaining such an army was very expensive and was not efficient or effective. Consequently, after 1991, the Polish armed forces had to be reduced and modernised. Since gaining membership in NATO, Poland has been developing its armed forces rapidly. Proximity to Russia requires adequate capabilities, and as a reaction to the current Ukrainian war, Poland has made significant steps toward strengthening its military power. These include purchasing K2 tanks, K9 howitzers and FA-50 aircraft from South Korea, which is probably the most important Polish defence deal in recent years.[1]

Post-communist Polish Military

After the downfall of the Soviet Union and the withdrawal of Soviet military troops from Poland by 1993, the two most important objectives of the Eastern European country were Western integration and the build-up of adequate defence capabilities to safeguard Polish sovereignty. The country’s intention to join the Western security structures motivated the development of the Polish military, which had begun after 1989, alongside the political reforms and changes in the government after more than 40 years of communist rule.

Military reforms under the Mazowiecki government

Becoming the first non-communist premier of Poland after 1945, Tadeusz Mazowiecki implemented major democratic reforms that led to the foundation of the Third Polish Republic. The Mazowiecki Cabinet was appointed in September 1989 and remained in office until the first democratic elections of Poland in 1991.[2]However, even within this short period, the Cabinet was able to launch significant reforms, including changes within the country’s armed forces.

During the rule of the Mazowiecki government, Poland was still a member of the Warsaw Pact, the dissolution of which was declared in February 1991.[3] As a member of the Soviet Union-led security system since 1955, the Polish armed forces had become its largest non-Soviet component. According to the data from the World Bank, the size of the Polish armed forces peaked in 1989, counting more than 350,000 military personnel.[4]Due to the strategic importance of the country’s location, an additional 30,000 Soviet ground and air troops were stationed on Polish soil between the late 1940s and 1993.[5]

Strategic guidelines

As democratic reforms began, an independent Polish military doctrine was elaborated in 1990, however, it was still partly under the communist influence in the heat of change. The new doctrine excluded the participation of the Polish armed forces in military action against other states unless an ally was attacked (meaning the members of the Pact back then) and described the stationing of Polish troops beyond state borders as contrary to the national interest. Nevertheless, the country’s Warsaw Pact membership could require participation in defensive operations abroad. The dissolution of the Warsaw Pact resulted in the need for a revised military doctrine for Poland.[6]

The new doctrine was determined by the Conventional Forces in Europe (CFE) agreements, signed in 1990, aiming to eliminate the Soviet Union’s advantage in conventional weaponry in Europe. As a member of the Warsaw Pact, Poland had to limit its conventional armament and its troops. The agreements determined the national ceiling for the Polish armed forces, causing a massive reduction in the country’s capabilities. The personnel had to be downsized to a maximum of 250,000, and around 200 combat aircraft and 1100 tanks had to be eliminated to comply with the CFE limits.[7]

|

Republic of Poland |

|

|

Tanks |

not more than 1730 units |

|

Armoured Combat vehicles which armoured infantry fighting vehicles and |

not more than 2150 units |

|

heavy armament combat vehicles including |

not more than 1700 units |

|

heavy armament combat vehicles |

not more than 107 units |

|

Artillery |

not more than 1610 units |

|

Combat Aircraft |

not more than 460 units |

|

Attack Helicopters |

not more than 130 units |

Figure 1: Agreement on the maximum level for holding of conventional arms and equipment of the Republic of Poland. Source: CFE Treaty[8]

As for the operational part of the new doctrine, it demanded that a large part of the Polish army and air force should be deployed to the eastern regions of Poland, bordering the Soviet Union, instead of the previous (Cold War-era) western orientation.[9]

Aligned with NATO

Poland established official relations with NATO in August 1990, and the acquisition of Western armaments began in the same year. Orientation towards Western organisations was also manifested in Poland’s 1992 security and defence strategy. The document set up the goal of maintaining armed forces with credible capability and of attaining NATO membership. The 1992 strategy was the first independent defence document of the post-communist Polish Republic. Given that the country joined NATO in 1999, the main strategic goal of the document was achieved.[10] The NATO membership meant Poland was expected to modernise its armed forces to ensure interoperability and cooperation with allied forces. Poland’s accession to NATO meant a key source of the technological modernisation of its armed forces.

Due to its geographical location, Poland is a frontline NATO country positioned between the alliance’s zone of influence and the Eastern threat, namely Russia. Thus, Poland has been increasing its defence spending, especially since the 2014 Russian aggression against Ukraine.

The Polish Armed Forces have already participated in NATO combat missions since 1996 as a partner and later as a member, including Kosovo, Afghanistan, and Iraq. Polish experiences from the latter two pointed to the need for armament modernisation so that they would meet NATO standards.

Polish Armed Forces development programme

Under the Warsaw Pact, Poland heavily relied on the Soviet arms industry. However, as an industrialised country, it gradually developed its own production, including the T-54, T-55 and T-72 tanks, in cooperation with Czechoslovakia. As political changes happened, Poland started to produce its domestically designed tanks after 1989, named ‘Twardy’. As procedure and technology were borrowed from the Soviet Union, many of the armaments manufactured in Poland were just refurbished or slightly changed models of the previous Soviet ones.[11]

The first Polish Armed Forces modernisation programme after accession to NATO was adopted in 2001. As for technological modernisation, it specified the air defence system and the command system of the Polish Armed Forces, including the acquisition of 60 multi-purpose aircraft, new tanks and the modernisation of the T-72 tanks and also the Mi-24 combat helicopters in line NATO standards.[12]

The first major Polish arms contract after the dissolution of the Soviet Union was the purchase of Rosomak armoured transports in 2003. They were licensed in Finland but produced in Poland. The largest arms purchase in the period leading up to the recent war in Ukraine happened in 2004 when 48 multi-role F-16 fighters were bought from Lockheed Martin.[13]

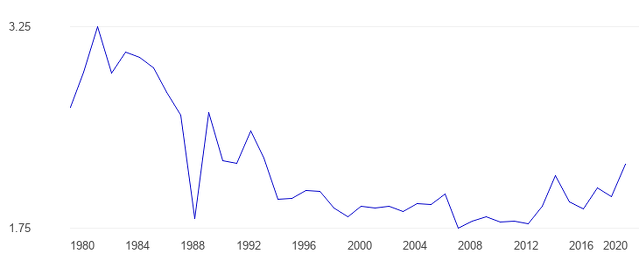

The first comprehensive strategy for military equipment modernisation was presented in 2012, namely the Technical Modernisation Plan. It covered the period between 2013 and 2022, and based on previous assumptions, it is projected to be one of the most extensive defence spending plans among the new NATO members with more than $15 billion worth of armaments programmes.[14] Also, Poland is one of the few countries that spend 2% of their GDP on defence and meet the NATO ambition level.

Figure 2: Poland Military spending of GDP. Source: The Global Economy[15]

Military expansion

In the new Armed Forces Development Programme of 2018, the intention to raise defence spending and the number of the military personnel to 250,000 and that of the Territorial Defence Force up to 50,000 was announced. In 2020 the number of full-time military personnel was around 110,000.[16] The need to replace the 30-40-year-old combat systems has long been recognised, and many steps were taken since the 2012 Polish modernisation plan.

Several large arms projects are related to the land forces, such as the replacement of 142 Leopard 2A4 tanks to the newer Leopard 2PL. An agreement about acquiring 250 M1A2 Abrams tanks from the United States was signed in April 2022.[17]

Beyond tanks, the wide-ranging modernisation of Polish artillery is also ongoing. An announcement was made in May 2022 that 500 High Mobility Artillery Rocket Systems (HIMARS) will be acquired from the US, and the procurement of more Patriot missile defence systems is planned.[18]

Although the modernisation of the land forces is prioritised due to its size and importance within the Polish armed forces, the replacement of the anti-aircraft systems consumes more money. The WISLA programme was launched in 2018, aiming to modernise air defence capabilities. It includes the acquisition of American Patriot PAC-3 air defence missile systems.[19] Besides, an agreement was made about acquiring short-range surface-to-air missile systems from the British subsidiary of the MBDA missile company. The total cost of the 23 Narew anti-aircraft systems is expected to be around €15 billion.[20] Acquisition of anti-air cannons and hand-held anti-air rockets were made from Polish companies. Since these require less advanced equipment and are at a lower price, the Polish defence industry can comply with these requirements.

Regarding the development of the air force, the modernisation of the Soviet-era equipment began in 2006 with the acquisition of the F-16 fighters that replaced the MiG-21 fleet. In 2020 an agreement was made about the purchase of 32 F-35 multi-role aircraft with a value of $4.6 billion between Lockheed Martin and Poland. The delivery is scheduled to begin in 2024; after which, Poland will be the first user of the equipment in the region.[21] Other air force development programmes are in process, such as the HARPIA programme since 2018, aiming to replace and upgrade the Soviet-era MiG-29 and Su-22 fighter aircraft.

Poland did not have a strong navy until the 20th century. However, events of the First World War created the need for a powerful maritime presence. It remained strategically crucial in the aftermath of the war as the Treaty of Versailles provided for the so-called ‘Polish corridor’, which gave the newly reconstituted Poland access to the Baltic Sea. The Post- Second World War territorial settlements secured Poland's access to the strategically important Baltic Sea, and the formerly neutral city of Gdansk also became part of the country.

The Baltic Sea remained a highly strategic area for Poland after the collapse of the Soviet Union due to the fact that Russia’s militarised enclave of Kaliningrad on its borders is considered to be a constant military threat. For example, the Iskander nuclear-capable missiles deployed in Kaliningrad in 2018 can reach about two-thirds of Poland. The country’s geographical proximity to Russia is a reason for weapon deployments on Polish land by the Western Allies. After the breakout of the Ukrainian war at the beginning of 2022, the US delivered two Patriot air defence systems to Poland to counter any potential threat from Russia to NATO territory.[22]

After the country’s NATO accession, the focus was put on international naval operations. In order to participate in joint operations, several modernisation programmes were needed. According to recent navy modernisation plans, the Ministry of National Defence is expected to spend PLN 24 billion (€5.1 billion) until 2025 on modernisation, and in 2050 it will increase by PLN 50 billion (€10.6 billion). These include the acquisition of new armaments and equipment. The latest plans are focused on the purchase of frigates and submarines, namely the ‘Miecznik’ and ‘Orka’ programmes, and also on the acquisition of 6 light rocket ships as part of the ‘Murena’ programme.[23]

In addition to the modernisation programmes mentioned above, the Technical Modernisation Plan 2020-2035, accepted in October 2019, highlights other important procurement programmes, such as KRUK (acquisition of modern attack helicopters), OBSERWATOR (satellites, reconnaissance aircraft) and CYBER.MIL (satellites, reconnaissance).[24]

Polish arms industry

Although the plans for the modernisation of the Polish Armed Forces are very ambitious, there are concerns about Poland’s defence industry. Several smaller arms programmes rely on the domestic sector, including companies such as Lucznik Weapons Factory. The current solution to strengthen the domestic defence industry is primarily to buy foreign licenses and the Polonization of purchased equipment, which can also return defence expenditures back to the economy.[25]

Consequences of the Russian-Ukrainian war

The recent war in Ukraine drew attention to the need for proper defensive potential and abilities. Poland’s geographical proximity to Russia has become particularly threatening in the current crisis and resulted in significant promises. In June 2022, Marius Blaszczak, Minister of National Defence of Poland, announced a forthcoming document, named Model 2035, which will be about developing all defence domains, including cyber and space.[26]

In April 2022, Poland took decisive measures in its reaction to the Russian-Ukrainian war. It ordered 250 Abram tanks, other heavy US battle vehicles, and training and logistics systems worth €4.32 billion. All the heavy equipment is expected to be delivered by 2026.[27]

As Polish defence spending already meets the 2% of GDP NATO target, a new national goal has been set to increase it to 3% in 2023. It is defined in the Defence of the Homeland document, which entered into force on 23 April 2022, two months after the breakout of the Russian-Ukrainian war. Initially, it had been planned to enter into force only in July, however, the new security situation moved the timeline up. The document also provides a new support fund to increase the expenditure on modernising the Armed Forces and sets the goal to double the size of its armed forces to approximately 300,000.[28]

The past six months resulted in rapid equipment acquisition amid a possible Russian threat. To bolster its armed forces, Poland is also up to purchasing South Korean armament, including 180 K2 Black Panther tanks, K9 howitzers and 48 FA-50 light combat fighter jets. The first pieces are expected to arrive at the end of 2022.[29] The reason behind recent purchases also involves the fact that Poland gave some of its arsenals to Ukraine to help its fight against Russia.

Military aid to Ukraine

Considered to be the third largest donor of military aid to Ukraine, Poland has contributed with weapons of immense value to the war since February 2022.[30] By bordering war-zone Ukraine, Poland has a vested interest in preventing the war from escalating. Poland is a very valuable NATO member when it comes to Moscow’s aggression since it has borders not just with Ukraine but also with Belarus and the Russian enclave Kaliningrad.

As Poland provided Ukraine with hundreds of tanks, artillery, ammunition, combat vehicles etc., it is now seeking help to fill the gaps in its own armament. The pieces of equipment sent to Ukraine were mainly used ones of older models. It exported military equipment with an overall estimated value of $1.7 billion, including, among others, over 200 T-72 tanks, a large number of Piorun portable surface-to-air missiles, and about 60 Krab self-propelled howitzers.[31] Poland is prepared to replace the equipment it gave away with used ones too, but the focus is rather put on purchasing new models. The previously mentioned Homeland Defence Act also serves this purpose by planning to increase the defence budget to 3% of the GDP.

Within NATO’s Eastern flank

In response to Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, NATO established a continuous air, land and maritime presence in its eastern flank, with the aim of strengthening the Alliance’s deterrence and defence posture. The four multinational battlegroups of 1,000 troops were created in 2017 in the four countries which are the most exposed to the Russian threat: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland. The Russian invasion of Ukraine at the beginning of 2022 resulted in an increased presence of the allied forces in additional four countries: Bulgaria, Hungary, Romania, and Slovakia.

Enhancing NATO’s forward presence, four multinational, combat-ready battlegroups are rotating in Poland and the three Baltic countries due to the 2016 Warsaw Summit. Since the outbreak of the Russian-Ukrainian war, four more battlegroups have been added, making it clear that an attack on one ally will be considered an attack on the whole alliance. In Poland, the battlegroups are let by the US, and the approximate total troop number is 1030 Croatia, Romania and the United Kingdom are the three other battlegroup contributor nations.[32]

The Ukrainian war resulted in strengthened cooperation between Poland and the US, and by that, it also increased interoperability across NATO’s entire Eastern flank. The 2022 NATO Summit in Madrid resulted in the declaration to establish a permanent headquarters in Poland for the US Fifth Army Corps.[33]

Being one of the easternmost members of NATO, Poland will always be in a position where it has to emphasise deterrence in the name of the alliance. The threat posed by Russia requires adequate capabilities from the Polish Armed Forces.

Conclusions

As a post-communist country, Poland had a long way to go to modernise its military. From a large but poorly equipped army, it had to create a modern and capable one over the last 30 years. Its NATO membership significantly boosted these efforts since the Polish Armed Forces had to become interoperable with the other militaries of the alliance so that it could participate in joint exercises and make the modernisation and acquisition of the equipment easier.

Several development programmes were announced during the past thirty years, but longer-term strategic thinking has become dominant only in the last decade. The current modernisation programmes are planned for longer terms, and the defence expenditure is expected to be more flexible, which could be useful, especially in today's volatile, uncertain security and economic environment.

The importance of strengthening the Polish army is especially timely since the Ukrainian war, due to the changed security system. Poland wants to modernise its army to deter the aggressor, namely Russia. Despite the promising commitments, there are doubts whether Poland can afford huge new defence-related investments in the near future, because it has already spent significant amounts of money on the modernisation and development of its armament, and there are still ongoing projects as well.

Bibliography

ADAMOWSKI, Jaroslaw: Poland inks $4.6 billion contract for F-35 fighter jets. In: Defense News, 31.01.2020, https://www.defensenews.com/global/europe/2020/01/31/poland-inks-46-billion-contract-for-f-35-fighter-jets/(25.07.2022.)

Agreement on maximum levels for holdings of conventional arms and equipment of the Union of Soviet Socialist republics, the People’s Republic of Bulgaria, the Hungarian Republic, the Republic of Poland, Romania and the Czech and Slovak Federal Republic in connection with the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe, 03.11.1990, https://nuke.fas.org/control/cfe/text/abudapest.htm#top (28.06.2022.)

GLOWACKI, Bartosz: Poland moves to buy HIMARS, capping major May modernization push. In: Breaking Defense, 06.06.2022, https://breakingdefense.com/2022/06/poland-moves-to-buy-himars-capping-major-may-modernization-push/ (30.07.2022.)

K2 tanks, K9 howitzers and FA-50 aircrafts – the Polish Army will receive powerful weapons, and the Polish defence industry will receive a strong impulse for development. In: Ministry of National Defence, 27.07.2022, https://www.gov.pl/web/national-defence/k2-tanks-k9-howitzers-and-fa-50-aircrafts--the-polish-army-will-receive-powerful-weapons-and-the-polish-defence-industry-will-receive-a-strong-impulse-for-development(28.06.2022.)

KUCHARCZYK, Maciej: Modernizing Poland’s Armed Forces In: Warsaw Institute, 06.06.2022, https://warsawinstitute.org/modernizing-polands-armed-forces/ (25.07.2022.)

MARCZUK, Karina: Democratization of Security and Defence Policies of Poland (1990-2010). In: Revue des Sciences Politiques, No. 36., pp. 80-93., Warsaw, University of Warsaw, 2012. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327545132_Democratization_of_Security_and_Defence_Policies_of_Poland_1990-2010 (01.07.2022.)

NATO’s Forward Presence. In: NATO Factsheets, 06.2022, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2022/6/pdf/2206-factsheet_efp_en.pdf (30.07.2022)

Navy Modernization Plans. In: Balti Military Expo. http://baltmilitary.amberexpo.pl/title,NAVY_MODERNIZATION_PLANS,pid,4471.html (25.07.2022.)

New Armed Forces Development Program. In: Ministry of National Defence, 28.11.2018, https://www.gov.pl/web/national-defence/new-armed-forces-development-program (10.07.2022.)

Permanent HQ for US Army’s V Corps to be set up in Poland says Biden. 06.29.2022. In: The First News. https://www.thefirstnews.com/article/permanent-hq-for-us-armys-v-corps-to-be-set-up-in-poland-says-biden-31386

Poland – Country Commercial Guide. In: International Trade Administration. https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/poland-defense-industry (25.07.2022.)

Poland – Military Doctrine. In: Country-data. http://www.country-data.com/cgi-bin/query/r-10787.html(28.06.2022.)

Poland Buys Short-Range Anti-Aircraft Missiles. In: The Defense Post, 26.04.2022, https://www.thedefensepost.com/2022/04/26/poland-short-range-anti-aircraft-missiles/ (25.07.2022.)

Poland has given Ukraine military aid worth at least $1.7 bn, expects allies to help fill the gaps. In: Notes from Poland. 15.06.2022. https://notesfrompoland.com/2022/06/15/poland-has-given-ukraine-military-aid-worth-at-least-1-7bn-expects-allies-to-help-fill-the-gaps/ (30.07.2022.)

Poland is third largest donor of military aid to Ukraine states BBC report. 02.07.2022, In: The First News. https://www.thefirstnews.com/article/poland-is-third-largest-donor-of-military-aid-to-ukraine-states-bbc-report-31474 (30.07.2022.)

Poland Military Size 1985-2022. In: Macrotrends. https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/POL/poland/military-army-size (28.06.2022.)

Poland Orders US Tanks, Other Battle Vehicles for $4.7B. In: The Defense Post, 06.04.2022, https://www.thedefensepost.com/2022/04/06/poland-us-tanks-vehicles/ (30.07.2022.)

Poland to buy South Korean tanks and combat planes. In: DW, 23.07.2022, https://www.dw.com/en/poland-to-buy-south-korean-tanks-and-combat-planes/a-62571314 (30.07.2022.)

Poland to purchase six more US Patriot air defense missile systems. In: Army Recognition, 29.05.2022, https://www.armyrecognition.com/defense_news_may_2022_global_security_army_industry/poland_to_purchase_six_more_us_patriot_air_defense_missile_systems.html(25.07.2022.)

Poland: Military spending, percent of GDP. In: The Global Economy. https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/Poland/mil_spend_gdp/ (10.07.2022.)

Polish Tanks and AFVs of the Cold War. In: Tanks-encyclopedia. https://tanks-encyclopedia.com/coldwar/Poland/cold-war-polish-tanks.php (01.07.2022.)

RIPLEY, Tim: The polish armed forces in the 1990s. In: Defense Analysis, 8(1), pp.88-90., London, Routledge, 2007. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/07430179208405527 (28.06.2022.)

SEGUIN, Barre R.: Why did Poland Choose the F-16? In: Marshall Center, 06.2007, https://www.marshallcenter.org/en/publications/occasional-papers/why-did-poland-choose-f-16-0 (10.07.2022.)

STRACQUALURSI, Veronica: These are the missile defense systems the US sent to Poland. 11.03.2022. In: CNN. https://edition.cnn.com/2022/03/10/politics/us-patriot-missile-defense-system-explainer/index.html(25.07.2022.)

SZAYNA, Thomas S.: The Military in a Postcommunist Poland. Santa Monica, RAND, 1991. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/notes/2009/N3309.pdf (28.06.2022.)

VERGUN, David: Poland Will Increase Defense Spending. In: U.S. Department of Defense, 20.04.2022, https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/3005337/poland-will-increase-defense-spending/(10.07.2022.)

What was the Warsaw Pact? https://www.nato.int/cps/us/natohq/declassified_138294.htm (28.06.2022.)

ZIELINSKI, Tadeusz: Transformation of the Polish Armed Forces: A perspective on the twentieth anniversary of Poland’s membership in the North Atlantic Alliance. In: Kwartalnik Bellona 700(1):33-47, Warsaw, Military Published Institute, 2020. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/346992623_Transformation_of_the_Polish_Armed_Forces_A_perspective_on_the_twentieth_anniversary_of_Poland%27s_membership_in_the_North_Atlantic_Alliance(01.07.2022.)

Endnotes

[1] K2 tanks, K9 howitzers and FA-50 aircrafts – the Polish Army will receive powerful weapons, and the Polish defence industry will receive a strong impulse for development, 27.07.2022. https://www.gov.pl/web/national-defence/k2-tanks-k9-howitzers-and-fa-50-aircrafts--the-polish-army-will-receive-powerful-weapons-and-the-polish-defence-industry-will-receive-a-strong-impulse-for-development(28.06.2022.)

[2] SZAYNA, Thomas S.: The Military in a Postcommunist Poland. Santa Monica, RAND, 1991. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/notes/2009/N3309.pdf (28.06.2022.)

[3] What was the Warsaw Pact? https://www.nato.int/cps/us/natohq/declassified_138294.htm (28.06.2022.)

[4] Poland Military Size 1985-2022. In: Macrotrends. https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/POL/poland/military-army-size (28.06.2022.)

[5] Poland – Military Doctrine. In: Country-data. http://www.country-data.com/cgi-bin/query/r-10787.html (28.06.2022.)

[6] Poland – Military Doctrine. In: Country-data. http://www.country-data.com/cgi-bin/query/r-10787.html (28.06.2022.)

[7] RIPLEY, Tim: The polish armed forces in the 1990s. In: Defense Analysis, 8(1), pp.88-90., London, Routledge, 2007. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/07430179208405527 (28.06.2022.)

[8] Agreement on maximum levels for holdings of conventional arms and equipment of the Union of Soviet Socialist republics, the People’s Republic of Bulgaria, the Hungarian Republic, the Republic of Poland, Romania and the Czech and Slovak Federal Republic in connection with the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe, 03.11.1990. https://nuke.fas.org/control/cfe/text/abudapest.htm#top (28.06.2022.)

[9] Poland – Military Doctrine. In: Country-data http://www.country-data.com/cgi-bin/query/r-10787.html (28.06.2022.)

[10] MARCZUK, Karina: Democratization of Security and Defence Policies of Poland (1990-2010). In: Revue des Sciences Politiques, No. 36., pp. 80-93., Warsaw, University of Warsaw, 2012. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327545132_Democratization_of_Security_and_Defence_Policies_of_Poland_1990-2010(01.07.2022.)

[11] Polish Tanks and AFVs of the Cold War. In: Tanks-encyclopedia. https://tanks-encyclopedia.com/coldwar/Poland/cold-war-polish-tanks.php (01.07.2022.)

[12] ZIELINSKI, Tadeusz: Transformation of the Polish Armed Forces: A perspective on the twentieth anniversary of Poland’s membership in the North Atlantic Alliance. In: Kwartalnik Bellona 700(1):33-47, Warsaw, Military Published Institute, 2020. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/346992623_Transformation_of_the_Polish_Armed_Forces_A_perspective_on_the_twentieth_anniversary_of_Poland%27s_membership_in_the_North_Atlantic_Alliance(01.07.2022.)

[13] SEGUIN, Barre R.: Why did Poland Choose the F-16? 06.2007. In: Marshall Center.https://www.marshallcenter.org/en/publications/occasional-papers/why-did-poland-choose-f-16-0 (10.07.2022.)

[14] KUCHARCZYK, Maciej: Modernizing Poland’s Armed Forces, 01.03.2017. In: Warsaw Institute. https://warsawinstitute.org/modernizing-polands-armed-forces/ (10.07.2022.)

[15] Poland: Military spending, percent of GDP. In: The Global Economy. https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/Poland/mil_spend_gdp/(10.07.2022.)

[16] New Armed Forces Development Program, 28.11.2018. In: Ministry of National Defence. https://www.gov.pl/web/national-defence/new-armed-forces-development-program (10.07.2022.)

[17] VERGUN, David: Poland Will Increase Defense Spending, 20.04.2022. In: U.S. Department of Defense. https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/3005337/poland-will-increase-defense-spending/ (10.07.2022.)

[18] KUCHARCZYK, Maciej: Modernizing Poland’s Armed Forces, 01.03.2017. In: Warsaw Institute. https://warsawinstitute.org/modernizing-polands-armed-forces/ (10.07.2022.)

[19] Poland to purchase six more US Patriot air defense missile systems, 29.05.2022. In: Army Recognition. https://www.armyrecognition.com/defense_news_may_2022_global_security_army_industry/poland_to_purchase_six_more_us_patriot_air_defense_missile_systems.html(25.07.2022.)

[20] Poland Buys Short-Range Anti-Aircraft Missiles, 26.04.2022. In: The Defense Post. https://www.thedefensepost.com/2022/04/26/poland-short-range-anti-aircraft-missiles/ (25.07.2022.)

[21] ADAMOWSKI, Jaroslaw: Poland inks $4.6 billion contract for F-35 fighter jets, 31.01.2020. In: Defense News. https://www.defensenews.com/global/europe/2020/01/31/poland-inks-46-billion-contract-for-f-35-fighter-jets/ (25.07.2022.)

[22] STRACQUALURSI, Veronica: These are the missile defense systems the US sent to Poland, 11.03.2022. In: CNN. https://edition.cnn.com/2022/03/10/politics/us-patriot-missile-defense-system-explainer/index.html (25.07.2022.)

[23] Navy Modernization Plans. In: Balti Military Expo. http://baltmilitary.amberexpo.pl/title,NAVY_MODERNIZATION_PLANS,pid,4471.html (25.07.2022.)

[24] Poland – Country Commercial Guide. In: International Trade Administration. https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/poland-defense-industry (25.07.2022.)

[25] KUCHARCZYK, Maciej: Modernizing Poland’s Armed Forces, 01.03.2017. In: Warsaw Institute. https://warsawinstitute.org/modernizing-polands-armed-forces/ (25.07.2022.)

[26] GLOWACKI, Bartosz: Poland moves to buy HIMARS, capping major May modernization push, 06.06.2022. In: Breaking Defense. https://breakingdefense.com/2022/06/poland-moves-to-buy-himars-capping-major-may-modernization-push/ (30.07.2022.)

[27] Poland Orders US Tanks, Other Battle Vehicles for $4.7B, 06.04.2022. In: The Defense Post. https://www.thedefensepost.com/2022/04/06/poland-us-tanks-vehicles/ (30.07.2022.)

[28] Poland – Country Commercial Guide. In: International Trade Administration. https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/poland-defense-industry (30.07.2022.)

[29] Poland to buy South Korean tanks and combat planes, 23.07.2022. In: DW. https://www.dw.com/en/poland-to-buy-south-korean-tanks-and-combat-planes/a-62571314 (30.07.2022.)

[30] Poland is third largest donor of military aid to Ukraine states BBC report, 02.07.2022. In: The First News. https://www.thefirstnews.com/article/poland-is-third-largest-donor-of-military-aid-to-ukraine-states-bbc-report-31474 (30.07.2022.)

[31] Poland has given Ukraine military aid worth at least $1.7 bn, expects allies to help fill the gaps, 15.06.2022. In: Notes from Poland. https://notesfrompoland.com/2022/06/15/poland-has-given-ukraine-military-aid-worth-at-least-1-7bn-expects-allies-to-help-fill-the-gaps/(30.07.2022.)

[32] NATO’s Forward Presence, 06.2022. In: NATO Factsheets. https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2022/6/pdf/2206-factsheet_efp_en.pdf (30.07.2022.)

[33] Permanent HQ for US Army’s V Corps to be set up in Poland says Biden, 06.29.2022. In: The First News. https://www.thefirstnews.com/article/permanent-hq-for-us-armys-v-corps-to-be-set-up-in-poland-says-biden-31386