Research / Geopolitics

Neutrality, a flexible commitment?

Non-alignment is an idea that has the habit of going into fashion once but it can suddenly become outdated when winds change. Throughout history there have been several moments when the best way to escape war and its human and economic consequences was to declare non-belligerence, and this logic also applied in the Cold War era when countries hesitating between the two blocks chose neutrality instead of alignment. What could be the main rationale behind choosing neutrality for countries like Yugoslavia, Spain, Turkey or Iran, and why did they give up this privilege in the end? No countries are remote islands, therefore the consent of the big fish in the strategy game must be secured if a nation wishes to maintain its neutrality. However, permanent neutrality seems more like the exception, not the rule.

Introduction

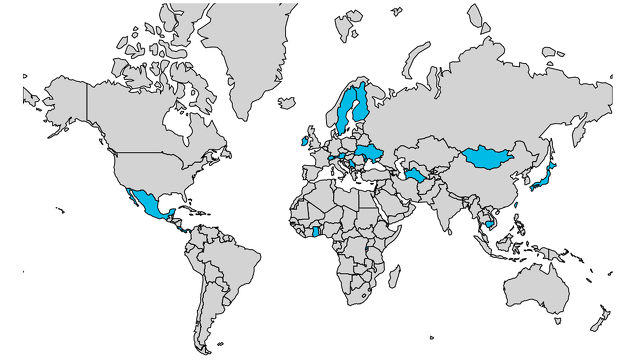

Neutrality or non-alignment is a well-known concept in international relations. But why do certain countries consider alliance systems to be the best guarantors of their security, while others go for the opposite solution, namely, neutrality or non-alignment? Neutrality describes a situation when in case of an armed conflict a given country does not align with either party. A country can choose neutrality when, based on its current economic or geopolitical interests it is best not to get involved in a war, but it can also choose to declare non-alignment as a permanent foreign policy and defence strategy in a way that it is acknowledged by its partners. Non-alignment therefore is a long-term strategy in general, but when a kind of opposition is formed between two states or blocks the appetite for it suddenly grows. Permanent non-alignment should be granted to states that commit not to get involved in armed conflicts hitherto, whatever circumstances might occur in the international arena. The legal concept of state neutrality was introduced into international law by Hague Convention respecting the Rights and Duties of Neutral Powers in Case of War or Land in 1907.[1] Neutrality is first and foremost a European concept, however, many prominent members of the Non-Aligned Movement were from other continents, especially Asia. In Europe currently neutral countries are Austria, Switzerland, Sweden, Finland and Ireland, while outside of Europe Laos, Costa Rica and Turkmenistan can be fitted into this category. They do not only agree not to rally in case of war on either one of the conflicting sides, but they also commit not to join any alliance systems with a military dimension.[2]

Figure 1: Neutral countries in the world 2022. Source: World Population Review[3]

When neutrals cooperated: the Non-Aligned Movement

Neutrality, or rather non-alignment, had a great importance during the Cold War era, when a group of countries, that did not want to join sides with either one of the superpowers, instead of joining the Eastern or the Western block, formed the Non-Aligned Movement. In the bi-polar reality of the second half of the 20th century non-alignment was almost the only way of avoiding being prone to the proxy wars initiated by the United States or the Soviet Union. The formation of the movement coincided with the collapse of the colonial systems too, at a time when both superpowers were eager to align the new-born states to their causes, either democracy and freedom, or socialism and communism. At the beginning, non-alignment was mostly characterised by the informal cooperation and co-decision of countries from the so called third world (areas where relatively new, developing states were formed). The representatives of these 29 countries met in Bandung in 1955 where they agreed on several principles to define their neutral position during the Cold War era. The core axioms they accepted were: self-determination, mutual respect for sovereignty, non-aggression, non-interference in internal affairs and equality among the nations.[4] The conference laid the ground for the Non-Aligned Movement that started to unfold shortly after it took place.

While the Bandung Conference had a primarily Asian-African focus, the Non-Aligned Movement created in 1960 already involved European forces too. Most prominently it was the leader of the former Yugoslavia Josip Broz Tito who stood up front of the movement, as he thought that could give him the momentum to alienate himself and his country from the Soviet Union, with which he was already at odds by then. Interesting however, that many of the participating countries of the Bandung Conference have already abandoned neutrality. Therefore, the question arises: What did they achieve by being neutral at one time of history and why did they decide to give this position up at another? Neutrality and non-alignment really had their peak during the Cold War, as a bipolar block-based system usually facilitates the creation of neutral states. In a multipolar setup neutrality has lost its meaning, but the concept emerges in popularity from time to time, especially when blocks are being formed.

Why did countries quit neutrality?

The case of Yugoslavia

As previously stated, Tito’s main motivation for taking up a leading role in the Non-Aligned Movement was his opposition to Joseph Stalin. His goal was to reform the communist system, and by doing so, to get rid of the Soviet supremacy, although due to ideological reasons he could not align his country with the West either. Obviously, the bottom-line of his strategy was to avoid getting trapped between the blocks. In Yugoslavia socialism did not necessarily mean submission to the will of Moscow, rather Tito set out to realise a “third way” in Cold War geopolitics.[5] While non-Alignment in Yugoslavia’s case meant the advantage of an increased leverage in foreign policy, it also required great effort to create a position in global politics other non-aligned nations might gravitate to.

The choice of non-alignment for Yugoslavia may have been an unavoidable one, as the country increasingly became isolated in Europe, as the continent was divided between the superpowers. Tito on the contrary had some leverage after breaking with the Soviet Union in 1948, and looked for new allies, which he could only find outside of Europe. In the end he not only averted complete seclusion from European diplomacy, but he managed to raise the prestige of Yugoslavian foreign policy approach which in time emerged as a true roll model for the not-aligned capitals of the globus.[6] Belgrade for a time became a hub of politicians that smoothly mediated between power blocks while maintaining their own countries’ sovereignties.

In the end though Belgrade gave up the policy of non-alignment as with the massive wave of decolonisation and the fact that most of the newly formed countries aligned themselves with either the Eastern or the Western Block the Movement was hollowed out. In Yugoslavia’s case the reason for declaring neutrality was the desire to maintain its sovereignty and role on the world stage. When liberty to act became questionable by the 1970’s (following the 1968 soviet intervention in Czecho-Slovakia) Tito already saw it best to cooperate with Leonid Brezhnev.

Yugoslavia clearly ceased to be neutral as it ceased to exist, but what about the countries that were members of the former Yugoslavia? Is there one that continued non-alignment among them? Croatia and Slovenia certainly did not, as they completed their way towards Euro-Atlantic integration, as a part of which they joined the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), a declared defence-oriented organisation. Serbia on the other hand can be considered a successor of Yugoslavian neutrality. Even more so as the country now heats its relations up with Tito’s former partners from the Non-Aligned Movement. Although with the dissolution of Yugoslavia its membership in the movement was suspended in 1992, Serbia has been an observer since 2001. As a result, in today’s troubling times, Belgrade can still utilise connections previously established within the movement, most of which do not recognise Kosovo. In addition to this staying in touch with old “allies” might boost Serbia’s defence industry, and at the same time helps the country to put on a balancing act between Western and non-Western powers.[7]

Figure 2: Former Yugoslav members states’ NATO accession. Source: nato.int[8]

Spain: neutrality out of desperation?

Spain, on the other hand, chose a different path. It had to declare neutrality at the brink of armed conflict, right before the First World War erupted. The main motivation was the country’s economic and military weakness; and the fact that Madrid was not in official alliance with any of the conflicting parties facilitated its decision. Spanish non-alignment though was far from a static concept it had to be adapted to the ever-changing geopolitical landscape of the 20th century. To announce official neutrality Spain was in a privileged position; it was surrounded by the Allies and it was in no strategic location for the outcome of the conflict. The country’s neutrality did not mean nonetheless that it did not maintain friendly relationships with the parties: its economic relevance dragged Madrid into the frontline as a crucial supplier in the war effort.[9]

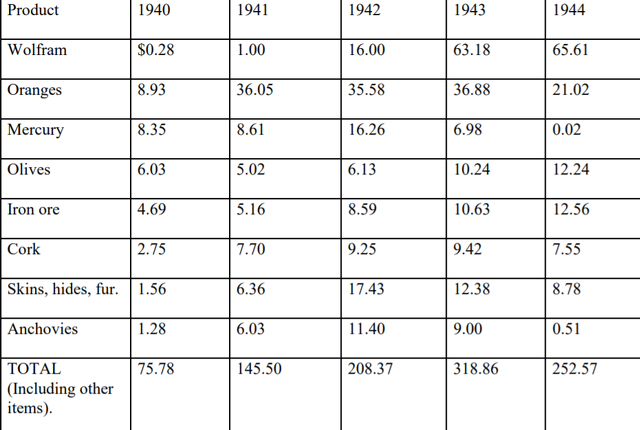

In the Second World War, after the devastation of the Civil War Spain opted again for neutrality. It did not mean however, that Madrid was not ideologically more aligned with Berlin than with its adversaries, the least of all with the Soviet Union. In spite of the fact that Spain declared non-belligerency in 1940, technically, it supported the Axis countries since the signing of the Steel Pact in 1939 with Germany and Italy. Luckily though for Madrid, Germany’s attack on the Soviet Union turned the strategic focus of the war to Eastern Europe, and then the focus turned towards North-West Europe, both directions left Spanish territory almost irrelevant in the war. In general, Madrid can be applauded for putting on a highly delicate balancing act where it avoided occupation from either of the foes and could evict unbearable burden from its economy. Spain also had to pay considerable attention not to cut its economic ties neither with the Allies nor with the Axis powers as it depended on trade with both groups, especially the United Kingdom and the United States. Nevertheless, during the Second World War, in a strictly legal definition, Spain was not granted neutrality, it only could manage not to get involved in actual fighting.[10]

Figure 3: In spite of not being militarily involved in the Second World War, Spain was a major supplier. Source: Caruana-Rockoff; 2000. [11]

After the neutral position Madrid had been trying to take on during the Second World War, during the Cold War it was unquestionably linked to the western alliance system, especially after it had signed an agreement with the United States in 1953. This defence pact allowed the Francoist regime to break its international isolation that characterised its foreign policy after the defeat of the fascist ideology in the Second World War. As a result, Washington even contributed to the development of Spanish defence capabilities.[12] The final goodbye to Spanish neutrality was hence waved in 1982, when after the end of the Franco-era and at the return of the monarchy Madrid stepped on the road towards a full Euro-Atlantic integration. Joining a military alliance therefore, was not the result of a threat to national security, but it was a wide-spread conviction of the Spanish that joining NATO is a necessary station on the way of joining the league of western democracies. The concept stuck, and the consultative referendum in 1986 confirmed the country’s joint will in this regard.[13]

Turkey: only align when you see the winning side

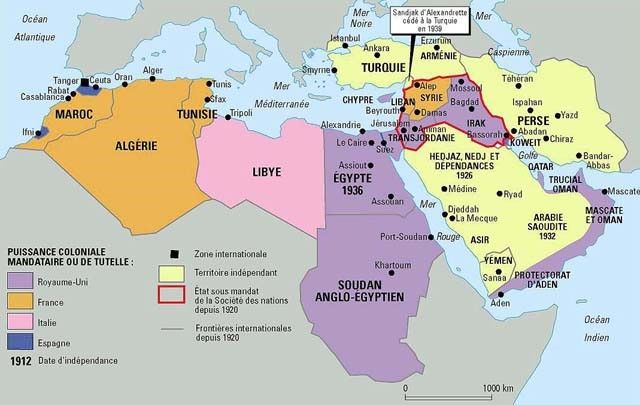

Turkey’s neutrality, such as that of Spain was motivated by a conflict forming on its doorstep. In this case, this was the Second World War where Ankara managed to keep the country out of the conflict, and for a while out of the forming blocks of the time. Contrary to Spain, Turkey had certain objectives it was hoping to achieve, even contemplated attacking the Soviet Union in order to seize the Caucasus and Crimea; besides, its territory was a strategic position for the belligerent foes.[14]

Figure 4: At the beginning of the Second World War Turkey was one of the few independent territories in the Middle East. Source: LeMonde diplomatique[15]

Turkey’s most important goal between 1939 and 1945 was to stay out of the war. This wish at the beginning of the war seemed very difficult to be honoured as Turkey was caught between the Axis and the Allied powers. However, Turkey started to build strong economic relations early on with the latter. By the end of the war, when it was apparent that the Allied countries would win the war, Turkey was inclined to expressively choose their side, hence abandon it neutral position.

What did bring Turkey’s non-alignment approach to an untimely end, was the fact that after having defeated Germany Moscow started to exert big pressure on the country in order to integrate it into its block, but also for putting its hand on an exit to the Mediterranean Sea. As a result, Ankara turned to Washington as it feared for Turkey’s sovereignty.[16] Even if Turkey did not feature among the founding members of NATO, it swiftly joined the organisation during the first wave of its enlargement, in 1952. Joining NATO was not only a security guarantee for Ankara, but it was also a means to solidify the western identity of the relatively young Turkish Republic. By doing so Turkey had solidified its strategic relevance in the Cold War era, when it served as a barrier for the Soviet Union to reach the Mediterranean Sea, and as a foothold for Western Powers in the Middle East.[17]

Overall, in Turkey’s case we can say, that after the devastating outcome of its picking the wrong side in the First World War, Ankara did not want to commit the same mistake again, so it played its cards wisely until it became obvious which alliance they should join. Accordingly, when their sovereignty and freedom was threatened at the dawn of the Cold War, Turkey, contrary to its previous lingering, did not hesitate long to align itself with a power that was able to offer it the most. Neutrality for the Turkish therefore was never a security policy principle, but rather a flexible position to take…until it served them no more.

Iran: neutrality or invasion

Iran is yet another country that at one point in history declared non-alignment, but when tides changed it altered its position. Iran after the First World War became occupied by British and Soviet forces despite its declared neutrality. In the turbulent years following up to the brake out of the Second World War Iran fought heavily to restore its independence and sovereignty, however remotely the country was aligned with the British. Despite the ideologically triggered distaste of the Nazi elite to cooperate with the peoples of the Middle East on an equal basis they sought to improve relations with the Persian state to use its strategic position in the region. At first, their attempts were appealing to the Iranian leaders, as they hoped to get rid of the interference of colonial powers.[18]

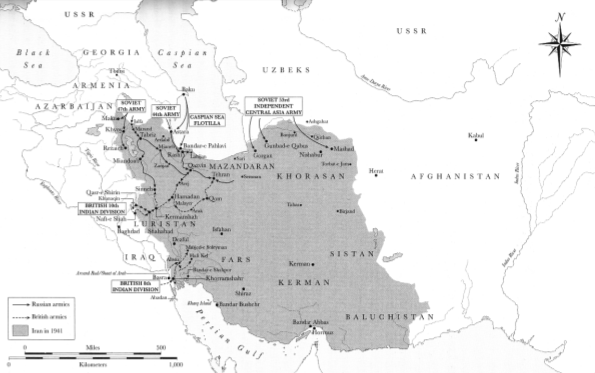

Similarly to Spain and Turkey, Iran also saw it best to declare non-belligerence, precisely in the attempt of protecting its national sovereignty and independence. But Iran was not as lucky or as agile as Spain or Turkey managed to be, as the country was occupied by Great Britain and the Soviet Union parallelly in 1941. Since neutrality was only declared two years earlier in 1939 Iran was not able to enjoy its status for long. The Allied Forces justified their actions by claiming that had they not occupied Persian territory Germany would have certainly invaded it and then Berlin would have been able to exploit both its strategic and supply advantages.[19] As a result, in the end, despite the declared wish of the acknowledged Iranian government the country had to get involved in the war and its sovereignty was also breached.

Figure 5: Declared neutrality can be disregarded when necessary: Soviet and British troops occupied Iranian territory during WWII despite of its status. Source: University of Calgary[20]

As the cold war started to freeze into international relations Iran as most other countries of the world had to decide which superpower to side with. Iran’s geographical situation between the Soviet Union and the Persian Gulf and its crude oil reserves both made it a valuable asset in the eyes of Washington and Moscow alike. Until the Islamic Revolution that swept through the country in 1979 Iran’s choice lied with the United States that was able to stir Tehran into its direction both economically and ideologically.[21] After Khomeini Ayatollah rose to power and the Iranian regime solidified, the country’s alignment was harder and harder to identify, though it certainly ceased to be an American ally.

Conclusion

As the article suggests the status of neutrality can be declared for several reasons. Either in order to make sure the country in question is able to defend its sovereignty and territorial integrity, or to avoid an economic and human disaster it is not capable of managing, or as a result of having learnt from historical mistakes. This article aimed to describe what reasons lead some countries to opt for non-alignment at one time of history yet they cease to be neutral at another. Outside forces that can trigger a non-alignment strategy are usually related to warfare or block politics. In such environment leaders might feel inclined to pull out of conflicts that do not benefit their countries – as long as they are allowed to do so…

As the above examples show for a country to be able to protect its neutral position consent of the international community is crucial. Occupation, desire to belong, outside threats and the promise of benefits all can lead to permanent alignment. In the case of Yugoslavia its non-alignment went into the grave with it, however elements of its neutrality logic are carried on by Serbia while other members of the former Yugoslavia aspired to join NATO as they considered it the gateway to the West. Spain also abandoned neutrality as democratisation called for Euro-Atlantic integration and economic considerations also suggested that alignment was becoming the best strategy. Turkey however, chose non-belligerence in the Second World War as it feared to commit the same mistake as it did during the First, yet when it feared for its own neck, it turned towards the western block for help. Iran’s neutrality on the other hand was trampled in the mud because of the crucial position it occupied in the war lines.

As a conclusion, the safest assumption to make is the following: these formerly neutral countries all had good reasons to declare non-alignment, but this position highly depended on international circumstances and on whether or not their wishes were respected by the international community. It is certain that the better strategic position a nation is situated in, the less likely it is allowed to be neutral, especially when a conflict is formed on its doorstep.

Bibliography

“A Brief Overview OF Non-Alignment Movement (NAM)”. In: Jatinverma.org. https://www.jatinverma.org/a-brief-overview-of-non-alignment-movement-nam (15. 02. 2022.)

“Bandung Conference (Asian-African Conference), 1955”. In: Office of the Historian. https://history.state.gov/milestones/1953-1960/bandung-conf (15. 02. 2022.)

BEAUMONT, Joan: “Great Britain and the Rights of Neutral Countries: The Case of Iran, 1941”. In: Journal of Contemporary History. Vol. 16. No. 1. January 1981.

“Convention (V) respecting the Rights and Duties of Neutral Powers and Persons in Case of War on Land. The Hague, 18 October 1907.” In: International Committee of the Red Cross. https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/ihl/INTRO/200?OpenDocument (15.02.2022.)

GÖKAY, Bülent: “Turkish Neutrality in the Second World War and Relations with the Soviet Union”. In: Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies Vol. 26 No. 2021. 6 pp.

HANN, Keith: ““A Rush and a Push and the Land is Ours”: Explaining the August 1941 Invasion of Iran”. In: University of Calgary. 24 January 2013.

“Iran and the United States in the Cold War”. In: The Gilder Lehman Institute of American History, AP US History Study Guide. https://ap.gilderlehrman.org/history-by-era/age-reagan/essays/iran-and-united-states-cold-war?period=9 (23. 02. 2022.)

“Iran during World War II”. In: Holocaust Encyclopedia, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/iran-during-world-war-ii (23. 02. 2022.)

LUELMO, Francisco José Rodrigo: “The accession of Spain to NATO”. In: CVCE.eu. 8 July 2016. https://www.cvce.eu/obj/the_accession_of_spain_to_nato-en-831ba342-0a7c-4ead-b35f-80fd52b01de9.html (16.02.2022.)

MARQUINA, Antonio: “The Spanish Neutrality during the Second World War”. In: American University International Law Review. Vol. 14. No.1. 1998. pp: 171-184.

MARTONYI, János et al: “Diplomáciai lexikon, A nemzetközi kapcsolatok kézikönyve”. Éghajlat Könyvkiadó. Budapest. 2018.

MOLDADOSSOVA, Altinay ; ZHARKINBAEVA, Roza: “The Problem of Turkey’s Neutrality During the Second World War in the Context of International Conferences”. In: The Journal of Slavic Military Studies Vol. 28, No. 2. 2015. pp. 401-413

“NATO on the map”. In: nato.int https://www.nato.int/nato-on-the-map/#lat=43.67188264030801&lon=17.993049495758342&zoom=1&layer-1&infoBox=The%20former%20Yugoslav%20Republic%20of%20Macedonia* (16. 02. 2022.)

“Neutral countries 2022”. In: World Population Review. https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/neutral-countries (15.02.2022.)

NIEBUHR, Robert: “Nonalignment as Yugoslavia’s Answer to Block Politics”. In: Journal of War Studies Vol.13, No. 1. 2011. pp. 146-179.

REKACEWICZ, Philippe: The Middle East in 1939. In: Le Monde diplomatique. August 1992. https://mondediplo.com/maps/middleeast1939 (18. 02. 2022.)

ROCKOFF, Hugh; CARUANA, Leonard: A Wolfram in Sheep's Clothing: Economic Warfare in Spain and Portugal, 1940-1944. In: Rutgers University, Department of Economics. Working Paoer No. 2000-8. 2000.

ROMERO SALVADÓ, Francisco J.: “Spain and the First World War: The Logic of Neutrality”. In: War in History Vol. 26. No. 1. 2019. pp. 44-64.

“Spain and NATO”. In: exterior.gob.es. http://www.exteriores.gob.es/Portal/en/PoliticaExteriorCooperacion/ProyeccionAtlantica/Paginas/EspLaOTAN.aspx (16. 02. 2022.)

TRÜLTZSCH, Arno: “An Almost Forgotten Legacy: Non-Aligned Yugoslavia in the United Nations and in the Making of Contemporary International Law”. In: Voices from the Sylff Community, Sylff Association. 16 November 2017. https://www.sylff.org/news_voices/23943/ (15.02.2022.)

“Turkey and NATO”. In: nato.int. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/declassified_191048.htm?selectedLocale=en (18. 02. 2022.)

VUKSANOVIC, Vuk: “Aligning with the Non-Aligned: Serbia Follows in the Footsteps of Old Yugoslavia”. In: RUSI. 19. October 2021. https://rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/aligning-non-aligned-serbia-follows-footsteps-old-yugoslavia (15.02.2022.)

Endnotes

[1] “Convention (V) respecting the Rights and Duties of Neutral Powers and Persons in Case of War on Land. The Hague, 18 October 1907.” In: International Committee of the Red Cross. https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/ihl/INTRO/200?OpenDocument (15.02.2022.)

[2] MARTONYI, János et al: “Diplomáciai lexikon, A nemzetközi kapcsolatok kézikönyve”. Éghajlat Könyvkiadó. Budapest. 2018.

[3] “Neutral countries 2022”. In: World Population Review. https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/neutral-countries (15.02.2022.)

[4] “Bandung Conference (Asian-African Conference), 1955”. In: Office of the Historian. https://history.state.gov/milestones/1953-1960/bandung-conf (15. 02. 2022.)

[5] NIEBUHR, Robert: “Nonalignment as Yugoslavia’s Answer to Block Politics”. In: Journal of War Studies Vol.13, No. 1. 2011. pp. 146-179.

[6] TRÜLTZSCH, Arno: “An Almost Forgotten Legacy: Non-Aligned Yugoslavia in the United Nations and in the Making of Contemporary International Law”. In: Voices from the Sylff Community, Sylff Association. 16 November 2017. https://www.sylff.org/news_voices/23943/ (15.02.2022.)

[7] VUKSANOVIC, Vuk: “Aligning with the Non-Aligned: Serbia Follows in the Footsteps of Old Yugoslavia”. In: RUSI. 19. October 2021. https://rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/aligning-non-aligned-serbia-follows-footsteps-old-yugoslavia (15.02.2022.)

[8] “NATO on the map”. In: nato.int https://www.nato.int/nato-on-the-map/#lat=43.67188264030801&lon=17.993049495758342&zoom=1&layer-1&infoBox=The%20former%20Yugoslav%20Republic%20of%20Macedonia* (16. 02. 2022.)

[9] ROMERO SALVADÓ, Francisco J.: “Spain and the First World War: The Logic of Neutrality”. In: War in History Vol. 26. No. 1. 2019. pp. 44-64.

[10] MARQUINA, Antonio: “The Spanish Neutrality during the Second World War”. In: American University International Law Review. Vol. 14. No.1. 1998. pp: 171-184.

[11] ROCKOFF, Hugh; CARUANA, Leonard: A Wolfram in Sheep's Clothing: Economic Warfare in Spain and Portugal, 1940-1944. In: Rutgers University, Department of Economics. Working Paoer No. 2000-8. 2000.

[12] LUELMO, Francisco José Rodrigo: “The accession of Spain to NATO”. In: CVCE.eu. 8 July 2016. https://www.cvce.eu/obj/the_accession_of_spain_to_nato-en-831ba342-0a7c-4ead-b35f-80fd52b01de9.html (16.02.2022.)

[13] “Spain and NATO”. In: exterior.gob.es. http://www.exteriores.gob.es/Portal/en/PoliticaExteriorCooperacion/ProyeccionAtlantica/Paginas/EspLaOTAN.aspx (16. 02. 2022.)

[14] MOLDADOSSOVA, Altinay ; ZHARKINBAEVA, Roza: “The Problem of Turkey’s Neutrality During the Second World War in the Context of International Conferences”. In: The Journal of Slavic Military Studies Vol. 28, No. 2. 2015. pp. 401-413

[15] REKACEWICZ, Philippe: The Middle East in 1939. In: Le Monde diplomatique. August 1992. https://mondediplo.com/maps/middleeast1939 (18. 02. 2022.)

[16] GÖKAY, Bülent: “Turkish Neutrality in the Second World War and Relations with the Soviet Union”. In: Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies Vol. 26 No. 2021. 6 pp.

[17] “Turkey and NATO”. In: nato.int. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/declassified_191048.htm?selectedLocale=en (18. 02. 2022.)

[18] “Iran during World War II”. In: Holocaust Encyclopedia, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/iran-during-world-war-ii (23. 02. 2022.)

[19] BEAUMONT, Joan: “Great Britain and the Rights of Neutral Countries: The Case of Iran, 1941”. In: Journal of Contemporary History. Vol. 16. No. 1. January 1981.

[20] HANN, Keith: ““A Rush and a Push and the Land is Ours”: Explaining the August 1941 Invasion of Iran”. In: University of Calgary. 24 January 2013.

[21] “Iran and the United States in the Cold War”. In: The Gilder Lehman Institute of American History, AP US History Study Guide. https://ap.gilderlehrman.org/history-by-era/age-reagan/essays/iran-and-united-states-cold-war?period=9 (23. 02. 2022.)