Research / Geopolitics

On the edge of Europe - Military developments in Britain since the end of the bipolar world order

Britain is undoubtedly part of the Western alliance system; therefore, it shapes its military doctrine in accordance with the NATO principles, ever since its foundation in 1949. Since then, a number of factors changed in the international system: first the bipolar world order collapsed, and now, we are experiencing a major destabilising period again. The UK military strategy and the development of its capabilities had to follow the rhythm of the accelerating pace of changes. After the end of the Cold War, British strategy first aimed at creating an armed force that is interoperable with NATO equipment, capable of giving rapid responses in crisis situations and deployable in out of area missions. With the war in Ukraine however, this goal might be altered a little bit, as it becomes clear that regular warfare is not only not outdated yet, but it can be fought on European soil as well.

British military throughout the decades

Britain never considered itself an exclusively European power, it has always rather been focusing on its global interests, that is now reflected in the “Global Britain” strategy applied after Brexit. Historically, in order to be able to focus on what was outside of Europe, London had to make sure that there was a balance of power on the continent. To achieve this, the United Kingdom often had to change alliances, always creating a coalition against the continental hegemon. This could be kept up until the 20th century, when a long-term strong military alliance formed between London and Washington. The British security policy has been conducted in line with the goals and principles of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), ever since its foundation in 1949; the UK as a founding member of the alliance has been in the core of this military cooperation. During the years of the Cold War London had always shown great commitment to participate in the Alliance’s activities, while trying to turn the focus towards the control of the seas, which for Britain - and island and an ex-colonial power – has been a constant a priority.[1]

The credo of the British Army is the protection of the nation and its dependent territories, therefore 96% of the personnel is stationed on national territory. It does not come as a surprise that the United Kingdom possesses one of the most capable armed forces in the world, in addition to being a nuclear power and occupying a permanent seat in the United Nations Security Council. Although the soldiers serving in the army are remarkably well-trained for combat, they can also be deployed in the case of a natural or man-made disaster. Prevention is the first and foremost task of the army in cooperation with partners all over the globe. This involves British boots on the ground in areas with a high risk of conflict in Africa, Asia, and Eastern Europe even. Today there are 5,900 military personnel stationed outside of the United Kingdom 65% is located in Europe, 16% is stationed in North America, while 6% is to be found in the Middle East and North Africa region.[2] According to the national interests the main goal of the armed forces is to tackle the causes of instability and give a rapid response when conflict emerges. But the military is for more than prevention, it is also well-prepared for conducting operations independently, with NATO, or with key allies such as the US or France when it comes to fighting the nation’s enemies.[3]

Figure1: British troops deployed overseas in 2015. Source: BBC[4]

After the Cold War

When the strictly bipolar world order ended in 1989-1991 the threat previously posed by the Soviet Union disappeared and as a result, the involvement of the United States in European security shrank. The defence policy of Britain in the 1990s was built on three main pillars. The most important was, of course, the ability to protect the nation and its dependent territories, which meant the preservation of the independent nuclear deterrent force, while other areas became neglected. The Trident programme was the main priority during this time. The second pillar was European protection within the North-Atlantic Alliance, while the third pillar included all other missions and operations conducted mostly under the egis of the United Nations. After the Cold War and with the disappearance of the imminent Soviet threat defence spending was cut back, affecting the conventional forces most severely, as the general idea was to replace huge armed forces fit for conventional warfare with new, flexible, highly trained units, able to be deployed in high-precision situations.[5] While in 1990 the total number of the personnel was 305,800, by 2000 this was reduced to 207,600.[6]

The end of the bi-polar world order indeed brought a drastic change in the international defence structure, which then introduced the need for the modernisation of the British military infrastructure. Realizing a consistent continuous development is not easy, especially in Britain, where the Labour and the Conservative governments came alternating, making it nearly impossible to detect firm patterns in the long-term priority shaping of the military field. Convergence in the military strategy could only be achieved if there are constant defence policy objectives every consecutive government works towards. Moreover, the policy instruments should be available in an equal measure for every government, while the institutional forums are not within the grasp of political parties, but they represent a continuum in strategic planning. Furthermore, in spite of the political changes the modernisation is pursued by the same amount of enthusiasm regardless of the composition of the political elite at the moment. For the UK the objective was to shift from its Cold War role of territorial and alliance defence to become a global force that is able to perform well in low-high intensity expeditionary crisis-management operations as part of multinational coalitions. In order to achieve that, they set up a Joint Reaction Force and more flexible planning and command capabilities by 1996-1997. Capability development kept in mind the requirements of asymmetric and net-centric warfare. We must not forget though, that even if the threat of the Soviet Union disappeared the UK continued to prioritise NATO as the primary forum of international military cooperation. At the same time London started to take part in the European Security and Defence Policy, in addition to tightening the military engagement with France as part of the Saint Malo Accord.[7]

Between 1990 and 2000 we can detect an important change in the philosophy the British defence planning adopted: during the Cold War they did not refrain from doing things violently, if need be; while after the fall of the iron curtain the goal became to achieve favourable outcomes, preferably in a non-violent manner. Of course, following the euphoria of the collapse of the Soviet Union, push factors lacked from behind the motivation to innovate. Nevertheless, threats soon presented themselves, if not as a belligerent foe, but the British army got involved in the management of crisis situations in Iraq, Afghanistan, Bosnia, Sierra Leone and Kosovo. The second push factor was that other countries, allies and enemies alike started to increase their potential, so the UK did not want to fall behind.[8] The transformation from a regular army to a modern, task-oriented and skilled military naturally required an enormous amount of time, money and effort. The new defence industry had to be built on five pillars: skilled workforce; smoothly processed, high-quality products; next-generation technology; and modern manufacturing facilities.[9] Therefore by 2021 the United Kingdom had the fourth largest military spending in the world, that amounted to USD 68.4 billion that year.[10]

Adapting to the ‘Competitive Age’

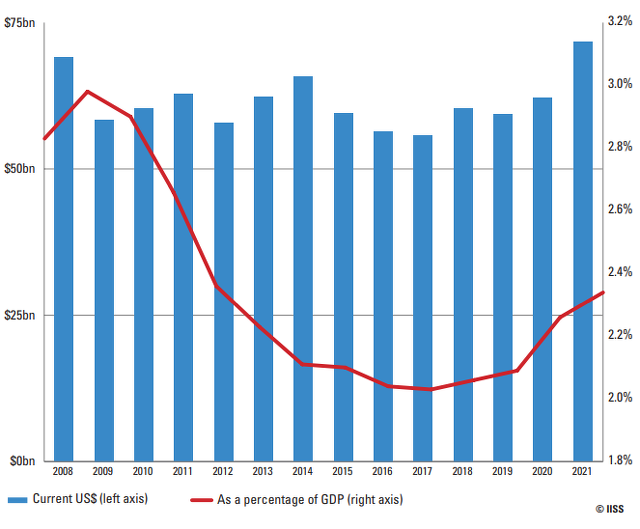

The so called “Competitive Age” is the one, where the United Kingdom after Brexit is pursuing to achieve the status of a “Global Britain” which is a concept they apply in the military field as well. This is a global situation where the previous international order is becoming ever more fragmented and where the status quo before is being questioned by assertive powers such as China or Russia for instance. It is worth highlighting though, that when most Western powers shifted their strategic focus to the China-Pacific area, London insisted that Russia still is and will remain to be the most acute direct threat to the UK. After a period when the defence spending was below 2% of the GDP it now passes the 2% NATO threshold, however it is still far less than the 4% in 1990[11]. Nevertheless it is set to increase to meet the challenges of the “Competitive Age”. The distribution of the assets was also set to change in 2021, as the new strategy envisaged an increased number of maritime capabilities and a reduction of air- and land-based forces.

Figure 2: UK defence expenditure in current USD and as a percentage of GDP. Source: Strategic Comments 2021.[12]

According to the British Integrated Review[13] there are going to be four trends shaping the next era and determine how the international order will change. These are: geopolitical and geo-economic shifts; the systematic competition between states, values and governments; increased technological change; and transnational challenges. But what are the threats that the UK and its allies might face in the new world order? When the 2021 integrated review was published there had not been a war on European soil since the Second World War, yet Russia has always been seen as an assertive power from London even after the Cold War ended. Countries mentioned as raising concerns for the UK government in addition to Russia, are Iran and North Korea. The Ukraine war now is a regular threat, that most European armies did not anticipate, rather they were preparing for irregular challenges including non-state actors, terrorism, espionage, political interference, sabotage, assassination and poisonings, electoral interference, disinformation, propaganda, cyber operations and intellectual property theft.[14]

The beginning of the current decade saw some radical transformations introduced to the British Army, although plans for their launch have already been formed weigh before the war erupted in Ukraine. The transformation programme announced in 2020 is called the “Future Soldier” which is going to be the most remarkable modernisation scheme seen in the sector for decades. The reform has been enshrined in the Integrated Review and is going to be supported by an increased defence spending. The explanation for this ambitious project was that Britain needed to properly prepare for being able to respond to the next-generation threats that are likely to emerge across the globe. During the period 2020-2030 the government pledged to invest an additional £8.6 billion to the purchase of military equipment. This means that a total of £41.3 billion will be spent on the most modern technologies, including Ajax, Boxer, Challenger 3, AH-64E Apache, long range precision files and un-crewed aerial systems. In addition to the material boost, Future Soldier also focuses on improving human capital and the strengthening of cyber defence capabilities and the enabling of the military to conduct foreign missions more effectively. For this latter a new Ranger Regiment was set up the end of 2021 concentrating on special operations. Furthermore, the British Army is expected to grow to over 100,000 troops by 2025.[15]

With the purpose of enhancing the operability of the armed forces additional £3 billion will be spent on new vehicles, long-range-rocket systems, air defences, drones, electronic warfare and cyber capabilities. The Royal Navy is also going to be modernised so that it can carry out specialist maritime security operations. As for the air capabilities the Future Combat Air System will contain crewed and uncrewed elements, which is a pioneering concept in today’s air defence. To support the long-term development of the army research and development projects will benefit from an investment worth £6.6 billion with a special focus on space capability building.[16] Space capability is considered to be the key of the 21st century military supremacy, which most countries strive for. This is the case with London, which has now already elaborated a strategy to be implemented in this sector to counter-balance the increasingly aggressive threat posed by Russia and China.[17]

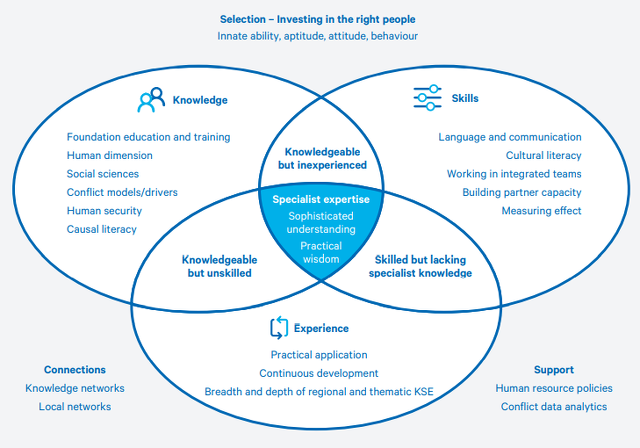

One of the key objectives of the new British security strategy is to improve engagement overseas in line with the political will to create a “Global Britain”. According to the Integrated Review there are moral, security and economic motives explaining why the UK must maintain its peacebuilding approach in conflict-prone and unstable regions. To their advantage, as of today, it appears that the UK armed forces and their considerable resources will enable the country to maintain and even enlarge its global network. Yet that requires further resources, mostly a highly-trained military personnel that will possess the necessary skills and experience to be engaged in such delicate operations.[18]

Figure 3: Developing understanding and practical wisdom for persistent engagement. Source: Davies, 2022.[19]

The war in Ukraine

London has always kept a close eye on what was happening in Ukraine, especially after the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014. Some experts might even claim, that the armed conflict between these two neighbouring countries is in fact simply the escalation of a conflict that has been going on for at least eight years.[20]. As a consequence, British military assistance provided for Ukraine has a longer history, than what we might perceive at first glance. In 2015 Operation Orbital was launched, that at first entailed non-lethal training and capacity building in Ukraine, and later on medical, operational and engineering trainings were also included. At that time though, contrary to the United States the UK rejected sending lethal arms to the country. In 2016 London and Kiev sealed a 15-year Memorandum of Understanding on closer defence cooperation, and in 2020 they signed a Political, Free Trade and Strategic Partnership that is designed to enhance defence cooperation. What is more, the same year, in 2020, Britain and Ukraine signed a Memorandum of Intent on following through the Naval Capabilities Enhancement Programme.[21]

And even though the United Kingdom was not directly affected by the 2014 crisis then, there are now numerous economic, social, political, humanitarian and legal implications of the current war in Ukraine, not only affecting the NATO as an organisation, but also its members, including Britain. The war in Ukraine can really play as a game-changer in British security strategy, as there already are voices demanding the revision of the Integrated Review published in 2021. For now, the UK provides weapons and aid to Ukraine in the fight against Russia. Parallelly, Britain also increases its commitment to NATO which means the deployment of its forces in Bulgaria and contributing additional forces to the troops already present in Poland and Estonia. What is more, as a result of the armed conflict in Ukraine, the United Kingdom also agreed on a mutual security deal with Finland and Sweden, two countries in the geographical grasp of Russia, that after the invasion of Ukraine decided to give up neutrality and to aim for NATO membership. London might be taking a serious risk by pledging to come to these allies’ aid should they be attacked. Although this agreement is a little less binding than the North Atlantic Treaty, but it already shows what length the Johnson-government would go to counteract Vladimir Putin.[22]

British Foreign Secretary Liz Truss admitted that the war in Ukraine will have an effect on the UK’s defence spending, and we can already notice a slight shift towards European stability instead of Indo-Pacific commitments from the behalf of the government when we look at the major strategic directions.[23] As it became clear for the UK that the age of regular warfare is not over yet, the government is highly aware of what impact it can have on the country. The stakes are fairly high, as despite that Ukraine is not a member of the European Union, neither of the NATO, the UK is committed to preserving a democratic government in Kiev. Nevertheless, by providing support for Ukraine, Britain also wants to set an example for China to dismiss its plans of reunifying Taiwan with the mainland.[24] Overall, what we can expect is that military development of the British armed forces will continue in the long-term, but there might be a need to revise the national strategies, or simply to adopt a highly flexible attitude, that might help London keep China at bay, remain the closest possible to the United States, and act as a grantor of European security, while supporting Ukraine in its war against Russia.

Bibliography

- BRADER, Claire: “’Defence in a Competitive Age’ and threats facing the UK”. In: House of Lords Library, UK Parliament. 15. October 2021. https://lordslibrary.parliament.uk/defence-in-a-competitive-age-and-threats-facing-the-uk/ (Accessed: 07.06.2022.)

- “British Army unveils most radical transformation in decades”. In: Ministry of Defence, GOV.UK. 25 November 2021. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/british-army-unveils-most-radical-transformation-in-decades (Accessed: 07.06.2022.)

- CHUTER, Andrew: “British military plans to spend big on space, but some wonder if it’s enough”. In: Defense News. 1 February 2022. https://www.defensenews.com/global/europe/2022/02/01/british-military-plans-to-spend-big-on-space-but-some-wonder-if-its-enough/ (Accessed: 07.06.2022.)

- “Countries with the highest military spending worldwide in 2021”. In: Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/262742/countries-with-the-highest-military-spending/ (Accessed: 16.06.2022.)

- DAVIES, Will: “Improving the engagement of UK armed forces overseas”. In: Research Paper, International Security Programme. January 2022.

- “Defence in a competitive age”. In: Ministry of Defence. March 2021.

- DORMAN, Andrew: “Reconciling Britain to Europe in the next Millenium: The Evolution of British Defence Policy in the post-Cold War Era”. In: 41st Annual Convention of the International Studies Association. 2000.

- DYSON, Tom: “Convergence and Divergence in Post-Cold War British French and German Military Reforms: Between International Structure and Executive Autonomy”. In: Security Studies. Vol. 17/4. 2008.

- FARRELL, Theo: “The Dynamics of British Military Transformation”. In: International Affairs. 84/4. 2008.

- “’Global Britain’: implication for UK military strategy and capability”. In: Strategic Comments. Vol. 27/7. 2021.

- “Global Britain in a Competitive Age: the Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy”. In: Government, Cabinet Office. 2. July 2021. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/global-britain-in-a-competitive-age-the-integrated-review-of-security-defence-development-and-foreign-policy/global-britain-in-a-competitive-age-the-integrated-review-of-security-defence-development-and-foreign-policy (Accessed: 15.06.2022.)

- HARDING, Megan – DEMPSEY, Noel: “UK defence personnel statistics”. In: House of Commons Library, Research Briefing. 01. November 2021. https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-7930/ (Accessed: 15.06.2022..)

- JACKSON, Liz: “Where are British troops deployed overseas?”. In. BBC. 1. December 2015. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-34919954 (Accessed: 14.06.2022.)

- LANDALE, James: “Ukraine crisis: What’s at stake for the UK?”. In: BBC. 30 January 2022. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-60159622 (Accessed: 07.06.2022.)

- “Military expenditure (% of GDP) – United Kingdom”. In: The World Bank Data https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.XPND.GD.ZS?locations=GB (Accessed: 15.06.2022.)

- MILLS, Claire: “Military assistance to Ukraine 2014-2021”. In: House of Commons Library, Research Briefing. 4 March 2022.

- “Number of personnel in the armed forces of the United Kingdom from 1900 to 2022”. In: Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/579773/number-of-personnel-in-uk-armed-forces/ (Accessed: 15.06.2022.)

- SCOTT, Edward: “Impact of the conflict in Ukraine: UK defence and the integrated review”. In: House of Lords Library, UK Parliament. 26 May 2022. https://lordslibrary.parliament.uk/impact-of-the-conflict-in-ukraine-uk-defence-and-the-integrated-review/ (Accessed: 07.06.2022.)

- “The United Kingdom and NATO”. In: North Atlantic Treaty Organization. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/declassified_162351.htm (Accessed: 09.06.2022.)

- “UK agrees mutual security deals with Finland and Sweden”. In: BBC. 11 May 2022. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-61408700 (Accessed: 09.06.2022.)

- WALKER, Nigel: “Ukraine crisis: A timeline (2014 – present)”. In: House of Commons Library, Research Briefing. 1 April 2022.

- “We are always ready to serve”. In: The British Army. https://www.army.mod.uk/what-we-do/ (Accessed: 07.06.2022.)

- YUE, Yi – HENSHAW, Michael: “An Holistic View of UK Military Capability Development”. In: Defense and Security Analysis. 25/1. 2009.

Endnotes

[1] “The United Kingdom and NATO”. In: North Atlantic Treaty Organization. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/declassified_162351.htm (Accessed: 09.06.2022.)

[2] HARDING, Megan – DEMPSEY, Noel: “UK defence personnel statistics”. In: House of Commons Library, Research Briefing. 01. November 2021. https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-7930/ (Accessed: 15.06.2022..)

[3] “We are always ready to serve”. In: The British Army. https://www.army.mod.uk/what-we-do/ (Accessed: 07.06.2022.)

[4] JACKSON, Liz: “Where are British troops deployed overseas?”. In. BBC. 1. December 2015. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-34919954 (Accessed: 14.06.2022.)

[5] DORMAN, Andrew: “Reconciling Britain to Europe in the next Millenium: The Evolution of British Defence Policy in the post-Cold War Era”. In: 41st Annual Convention of the International Studies Association. 2000.

[6] “Number of personnel in the armed forces of the United Kingdom from 1900 to 2022”. In: Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/579773/number-of-personnel-in-uk-armed-forces/ (Accessed: 15.06.2022.)

[7] DYSON, Tom: “Convergence and Divergence in Post-Cold War British French and German Military Reforms: Between International Structure and Executive Autonomy”. In: Security Studies. Vol. 17/4. 2008.

[8] FARRELL, Theo: “The Dynamics of British Military Transformation”. In: International Affairs. 84/4. 2008.

[9] YUE, Yi – HENSHAW, Michael: “An Holistic View of UK Military Capability Development”. In: Defense and Security Analysis. 25/1. 2009.

[10] “Countries with the highest military spending worldwide in 2021”. In: Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/262742/countries-with-the-highest-military-spending/ (Accessed: 16.06.2022.)

[11] “Military expenditure (% of GDP) – United Kingdom”. In: The World Bank Data https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.XPND.GD.ZS?locations=GB (Accessed: 15.06.2022.)

[12] “’Global Britain’: implication for UK military strategy and capability”. In: Strategic Comments. Vol. 27/7. 2021.

[13] “Global Britain in a Competitive Age: the Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy”. In: Government, Cabinet Office. 2. July 2021. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/global-britain-in-a-competitive-age-the-integrated-review-of-security-defence-development-and-foreign-policy/global-britain-in-a-competitive-age-the-integrated-review-of-security-defence-development-and-foreign-policy (Accessed: 15.06.2022.)

[14] BRADER, Claire: “’Defence in a Competitive Age’ and threats facing the UK”. In: House of Lords Library, UK Parliament. 15. October 2021. https://lordslibrary.parliament.uk/defence-in-a-competitive-age-and-threats-facing-the-uk/ (Accessed: 07.06.2022.)

[15]“British Army unveils most radical transformation in decades”. In: Ministry of Defence, GOV.UK. 25 November 2021. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/british-army-unveils-most-radical-transformation-in-decades (Accessed: 07.06.2022.)

[16] “Defence in a competitive age”. In: Ministry of Defence. March 2021.

[17] CHUTER, Andrew: “British military plans to spend big on space, but some wonder if it’s enough”. In: Defense News. 1 February 2022. https://www.defensenews.com/global/europe/2022/02/01/british-military-plans-to-spend-big-on-space-but-some-wonder-if-its-enough/ (Accessed: 07.06.2022.)

[18] DAVIES, Will: “Improving the engagement of UK armed forces overseas”. In: Research Paper, International Security Programme. January 2022.

[19] DAVIES, Will: “Improving the engagement of UK armed forces overseas”. In: Research Paper, International Security Programme. January 2022.

[20] WALKER, Nigel: “Ukraine crisis: A timeline (2014 – present)”. In: House of Commons Library, Research Briefing. 1 April 2022.

[21] MILLS, Claire: “Military assistance to Ukraine 2014-2021”. In: House of Commons Library, Research Briefing. 4 March 2022.

[22] “UK agrees mutual security deals with Finland and Sweden”. In: BBC. 11 May 2022. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-61408700 (Accessed: 09.06.2022.)

[23]SCOTT, Edward: “Impact of the conflict in Ukraine: UK defence and the integrated review”. In: House of Lords Library, UK Parliament. 26 May 2022. https://lordslibrary.parliament.uk/impact-of-the-conflict-in-ukraine-uk-defence-and-the-integrated-review/ (Accessed: 07.06.2022.)

[24]LANDALE, James: “Ukraine crisis: What’s at stake for the UK?”. In: BBC. 30 January 2022. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-60159622 (Accessed: 07.06.2022.)