Research / Geopolitics

Development of the Hungarian Defence Forces since 1989

In 2002 according to the Foreign Affairs magazine, “Hungary has won the prize for most disappointing new member of NATO”[i]. The mordant critique was unfair on the one hand, looking at the country’s committed participation in NATO’s foreign missions. But on the other hand, if we consider that the government was not able to fundamentally transform and modernise the military capacity or increase the defence spending neither in the ten years between the regime change and NATO membership nor in the decade after the country’s accession, criticism may seem fair. With the leeway of modernisation and structural changes, Hungary was not only unable to fulfil its mandatory contribution to the Alliance, but without adequate military capabilities, it jeopardised the security of the country itself too. In 2016 the long-awaited force development programme was launched, and now the country must make up for decades of backlogs in very challenging times.

From the Warsaw Pact to the NATO

Structural changes in the international security and political sphere or, in other words, the decomposition of the Cold War bipolar world brought significant changes for Hungary as well. Between 1989 and 1991, Hungary gradually got rid of the political system, military institutional ties and organisational memberships which bonded the country to the Eastern Bloc. On 23 October 1989, the Hungarian Republic was proclaimed; in 1990, free and general elections were held in the country for the first time since the Second World War; in June 1991, the last Soviet soldier left the country, and the Warsaw Pact and the Soviet Union were dissolved too by the end of the year.[ii] These changes gave Hungary the opportunity to reform its military capacity tailored for the capabilities and needs of the newly independent country. Given the new dynamics of the global and regional security environment, force reduction seemed to be a sensible decision for Hungary. One, that also fits into the international trends,[1] as with the dissolution of the bipolar world, the chances of a large-scale war between countries on the European continent significantly decreased. Governments realised that it is needless to maintain grand armed forces and grandiose defence spending.[iii]

[1] A spectacular example is the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE), signed in 1990 by NATO and WP countries. The CFE established comprehensive limits on key categories of conventional military equipment in Europe and mandated the destruction of excess weaponry.

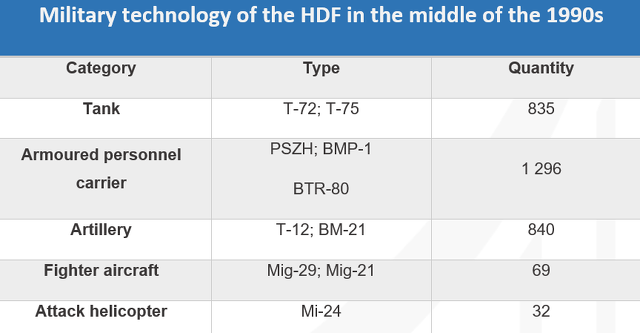

Military technology of the HDF in the 1990s with some types of equipment

(Source: András Katona[iv])

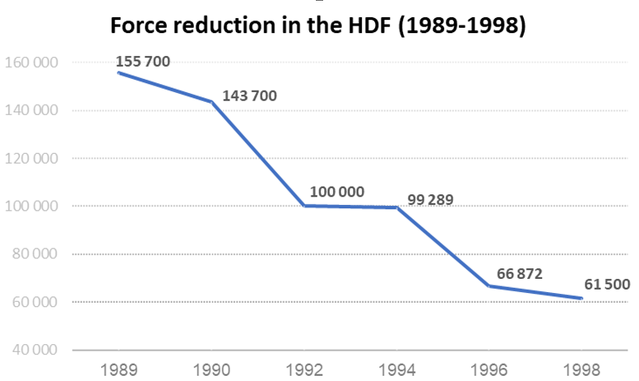

In Hungary, in parallel with the institutional changes and the depoliticization of the Hungarian People’s Army (renamed Hungarian Defence Forces), the first more significant armed forces reduction and dismantling occurred between 1989-1990 (see chart below). The Hungarian Defence Forces’ staff was further reduced by 35% between 1990 and 1993 while the amount of technical equipment decreased by 20-40% in the same period.[v] However, the defence sector would have required profound structural changes and reforms and the replacement, or at least, the modernisation of weaponry and equipment; due to the lack of resources and expertise, this was impossible.[vi] This lack of resources can be explained by the transformation of the country’s economy, which meant a severe setback and put the defence sector on a low priority. While the absence of expertise and experience in arms reform can be understood if we consider that decisions on security and defence had been handed down for decades by a very narrow political power elite and dictated by supranational circles. However, the first security policy and defence principles came out in 1993; the first National Security Strategy was only formulated in 2002, highlighting the sectoral deficit in expertise and in strategic guidance.[vii]

Force reduction in the HDF (1989-1998)

(Source: András Katona[viii])

The appearance of the ethnic and independentist insurgencies in the Balkans soon turned into a fierce war in 1991. The Yugoslav wars in the southern neighbourhood of Hungary had a positive effect on the country's defence development and prospects. On the one hand, the necessity and the importance of appropriate national defence capabilities increased in the eyes of the Hungarian public and decision-makers. On the other hand, the regional conflict valorised Hungary’s role and position in NATO's eyes and gave impetus to the country on the road to the much-coveted accession to NATO.[ix] In January 1996, the Hungarian Engineer Contingent (HEC) was deployed to Okučani, Croatia, to the NATO-led Implementation Force (IFOR) (later Stabilization Force) mission to give technical support and carry out tasks such as clearing mines, building roads and bridges or the clearing of riverbeds and sewage system.[x] Meanwhile, a Hungarian village, Taszár became the primary staging post for US peacekeeping forces and the base for aircraft support during Operation Allied Force in 1999.[xi]

In 1997 at the Madrid summit, NATO leaders invited the representatives of the Czech Republic, Poland, and Hungary to start accession talks with the Alliance. These three countries formally joined the Alliance on 12 March 1999.[xii] However, Hungary's accession to the NATO meant a significant success and a significant step on the road to integration into the Western political and security structure; Hungarian Defence Forces and the country’s defence sector as a whole still struggled with the lousy heritage of the Warsaw Pact both in a structural, a technical and a moral meaning. Fundamental structural changes and reforms had not been conducted in the ten years between the regime change and the country’s NATO accession; only downsizing and dismantling took place while military equipment, installations, supplies and bases have been highly depreciated.[xiii] By the end of the decade, the number of personnel of the Hungarian Defence Forces was decreased to 60-65 thousand. The military equipment of the HDF was not only outdated but was not interoperable with NATO since it was mainly soviet technology. Joining NATO gave Hungary the opportunity and urgent need for the deep restructuration of the Hungarian Armed Forces with the purpose of better performing tasks for the Alliance and of enhancing the interoperability of Hungarian capabilities.

Another decade without reform

As a NATO member

After the NATO accession, the country's defence capabilities and their role had to be reshaped and rethought, and the political-military leadership seemed to understand the profound transformation of the is HDF needed. In 1999 the Hungarian government ordered a strategic review of the defence sector and announced a comprehensive package of measures. The government decided to launch a ten-year development programme, which envisaged the army's further transformation and the reform of its structural composition through well-thought-out processes instead of ad-hoc decisions.[xiv] The measures also contained the proportion of the personnel, operational and development expenditures set at 40–30–30%. With the reduction of personnel, the HDF staff consisted of 45,000 people, with a significant change in the composition of the internal staff with the reduction of the number of high-ranking officers and the increase of the number of sergeants and officers. [xv] The first phase of modernisation would have sought to devote resources to the improvement of the working and living conditions of the army personnel. In the second stage (2003–2005), the training capability and readiness would have been increased, while in the third stage (2006–2009), the military’s technological modernisation would have taken place.[xvi] But unfortunately, in the years following the NATO accession, the Hungarian government's attempts to reform the HDF hollowed out, and the commitments the country made to the Alliance have consistently failed. In neither capabilities and modernisation nor defence spending (2% of GDP), could the country fulfil its promises. For which "Hungary has won the prize for most disappointing new member of NATO, and against some competition" – according to an article in Foreign Affairs from 2002.[xvii]

Significant changes in the immediate and global security environment at the beginning of the 21st century also required the rethinking of the national security strategy and the transformation and modernisation of the HDF. A democratic upheaval took place in Yugoslavia in October 2000, which reduced the tensions in the close neighbourhood of Hungary. Meanwhile, it became evident that seven countries would join NATO in the second round of enlargement, including adjacent Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia, which would contribute to the region's stability.[xviii] And last but not least, the terrorist attack on the United States on 11 September 2001 had the most remarkable impact on the global and the national security strategy. It became clear that the next decade would be the era of the “war on terror”, which required smaller, peacemaker, peacekeeper, and high readiness capabilities instead of conventional or territorial defence forces.

Therefore, Hungary’s defence sector was revised in 2002 but with a different mindset and method. Instead of a financial source based approach, it concentrated on the skills and capacities required for the country to be able to tackle the challenges of a new world order. The turbulent and rapid changes at the beginning of the century also indicate why the country needed two National Security Strategies within two years, in 2002 and 2004. These are also fundamentally different papers with new priorities derived from the changing security environment and the country’s successful accession to the EU.[xix]

Considering the requirements of modern warfare and the economic limitations of specific member states, NATO introduced a new mindset of burden-sharing to avoid duplication of capabilities within members. Thus, Hungary had the opportunity to build a force that contributes to joint capabilities with modular elements, which can perform tasks at a high level in the domestic and international environment. This meant that the country did not have to strive to develop a full-spectrum army, which led to a better allocation of scarce resources. Seven independent modular elements were established, an independent infantry battalion with the sustainability up to a month; one brigade support battalion; four tactical aircrafts and combat helicopters; short-range anti-aircraft missiles and cargo helicopters. [xx]

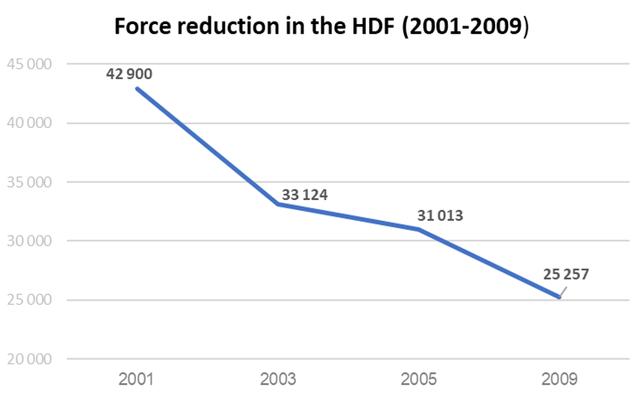

A meaningful change from this era was that in 2004 the Parliament decided to abolish the institution of the conscript army to set up a voluntary force. While only prudent renovation and modernisation took place in these years, the most known example from this period is the highly controversial signing of the lease agreement on fourteen JAS 39 Gripen fighter aircrafts. But defence spending was still unable to reach the promised 2% of the GDP in these years; furthermore, it gradually decreased after 2003 and stagnated around 1-1.2% in the following years.[xxi] Same as the number of troops which were reduced to under 25,000 by the end of the decade (see chart below)

Force reduction in the HDF (2001-2009)

(Source: András Katona[xxii])

The HDF in foreign missions

Hungary participated in several foreign peacekeeping and training missions since the 2000s within the framework of NATO, OSCE, UN, and the EU, which Hungary also became a member of in 2004. Hungary’s participation was unambiguously the declaration of the country’s commitment towards these organisations and, in the case of the NATO, a kind of compensation as the country was still unable to meet the requirements of the Alliance regarding interoperability, modernisation and defence expenditure. The positive consequence of participating in missions was that part of the HDF was able to receive new equipment, high-level training (mainly from the United States)[2], see new processes and gain international experience.[xxiii] In 2004 Hungary’s level of ambition for participating in foreign missions was maximised in 1000 troops, and in the following years, the number of Hungarian boots on the ground was constantly around this maximum.[xxiv] Main operation areas of the HDF are Bosnia and Herzegovina (IFOR, SFOR), Kosovo (KFOR), Afghanistan (ISAF) and Iraq (NMI) but from Congo to Cyprus and from the Sinai to Georgia numerous Hungarian troops carried out special operations.[xxv]

[2] With the help of the United States Army's Mobile Training Team, 34th Bercsényi László Battalion was transformed into a special operation battalion with the ability to conduct military operations on the entire spectrum of conflicts. This Special Forces Battalion participated in many foreign missions, including ISAF in Afghanistan.

The great impact of the economic crisis

The financial and economic crisis of 2008-2009 had a severe impact on the defence spending and sector not just in Hungary but throughout Europe. According to the European Defence Agency (EDA), defence spending in the EU member states fell by 11% between 2007 and 2013 due to the economic crisis. While capacity development spending fell by 22% between 2007 and 2014, reaching a low point at € 35.8 billion.[xxvi] Budget cuts in the sector resulted in an intense loss of capacity and delay in procurement and modernisation. The rearrangements of financial assets to other areas at the expense of the military by European governments could also happen because of a favourable security situation on the continent, which did not require investment in the defence sector.

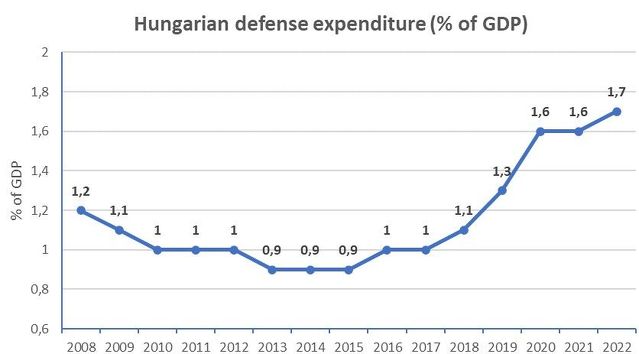

Hungary’s situation just completely fitted into these European trends as well. The financial and economic crisis resulted in a 16% reduction in defence spending only in 2010, and a slight decline continued until 2014. Military expenditure compared to the country’s GDP went down from 1.2% in 2008 to 0.79% in 2014 (see chart below).[xxvii] Between 2010 and 2012, the number of military personnel decreased by 2,200, while by 2014, more than 4,500 people were absent from the HDF structure. The main reason for that absence was the cut in wages of the military personnel. Still, the lack of sources also resulted in reduced involvement in foreign missions, declining capacity and the further delay of the long-overdue modernisation of outdated equipment.[xxviii] The only achievement from this period is that in 2011, the legislation for the development of the Voluntary Reserve System was drafted, and from 2012 the system was ready to be refilled.[xxix]

In 2012, with the new National Security Strategy and the new National Military Strategy (NMS), the government committed itself to reversing the deterioration of the defence sector. To build a sustainable force, the NMS ordered a 40-30-30% share of personnel, operational and development expenditures in the defence budget in the medium term. In 2014 the government decided to reach the 2% of the GDP in defence expenditure by 2024 with 20% of this to be spent on development.[xxx]

Changes in the Hungarian defence expenditure (% of GDP)

(Source: SVKI[xxxi])

Increasing the national defence budget and, in general, the valorisation of security and defence were also international tendencies in the second half of the 2010s. The European political and security stance saw many changes varying from the 2011 “Arab Spring” to the 2014 Russia-Ukraine conflict and then the 2015 migration crisis in Europe, which seriously impacted the European and the Euro-Atlantic security perception. The subject of common defence has returned to the heart of the strategic dialogue among NATO members, especially in Central Europe. Strengthening military capabilities and readiness, coordinating their strategic thinking, defence planning, military procurement, and force modernisation programmes within the collective defence system require more human knowledge and financial capital.[xxxii] It is also why the former US President Donald Trump fiercely put his feet down demanding fair burden-sharing by fulfilling the obligation of spending at least 2% of the GDP on defence and earmark 20% for development. America’s demands are rightful, after all the US military expenditure as a share of GDP never went below 3.3%, even at the time of the economic crisis.[xxxiii] Soon NATO countries reaffirmed their commitment to increasing their defence spending in The Wales Declaration on the Transatlantic Bond in 2014.[xxxiv]

Arriving in the 21st century

The long-awaited modernisation – “Zrínyi 2026."

In 2016, as an answer to the deteriorating security environment, the Hungarian government announced the “Zrínyi 2026 Defence and Force Development Programme” with the promise of realising the long-awaited and well-needed modernisation and reformation of the HDF. The ten-year-long (2016-2026) comprehensive project aims at modernising and revitalising the defence sector with the help of which the Hungarian Defence Forces can become a modern decisive force, at further strengthening Hungary’s security and the common defence of Europe and NATO. It also has the goal of making the military career an attractive opportunity and a highly respected profession in the eyes of society. For the ten years, a total of 3,500 billion forints have been separated to reach the 2% of the GDP military expenditure by 2024.[xxxv] Military budget was doubled from 250 billion in 2015 to 513 billion in 2019 which meant around 1.3% of the country’s GDP (see chart above).

Acquired military technologies

Regarding military technology, the large-scale acquisitions were made in the first half of the programme to replace obsolete technology, including vehicles, arms, devices and gears, to more modern and interoperable equipment. Acquisitions are made in light of Hungary's 2014 commitment to NATO in capabilities and contribution. The country promised to contribute to the common defence capabilities with a heavy brigade by 2028; therefore, military equipment will be procured in accordance of this purpose. [xxxvi]

As a matter of ground forces, Leopard 2A4 and 2A7+ tanks, a total of 44, were purchased from the German Krauss-Maffei Wegmann company in 2018. It would mean 50 years of technological step ahead as they will replace the Russian (Soviet) T-72s. Also, the KMW company's PzH2000 self-propelled gun has been put into operation in the Hungarian Defence Forces, and a contract for 200 "Puma" infantry fighting vehicles were also signed for with the German manufacturer.[xxxvii]

Another deal for 218 Lynx KF41 armoured fighting vehicles was made for 700 billion forints with the German Rheinmetall corporation in 2019. The agreement is not just about a purchase but a cooperation between the Hungarian government and Rheinmetall. A military factory will be built in Hungary, which will produce 172 of the total amounts of the vehicles. This way, the cooperation benefits the development of the Hungarian military industry, which is also a primary objective of the government and the "Zrínyi 2026". Within the same framework, "Gibran" armoured tactical vehicles (based on the Turkish Ejder Yalçın model) will be produced for the HDF.

Last year, NASAMS medium-range anti-aircraft missile system was purchased from Norwegian and American companies. Another contract was made to procure ELM-2084 multi-mission radars with Rheinmetall Canada. The radar is based on the high-end Israeli technology used in the "Iron Dome" system. It can detect and track both aircraft and ballistic targets and provide fire control guidance for missile interception or artillery air defence.

As part of the aircraft and airlifting capability modernisation, the Hungarian government agreed with the European Airbus aerospace company, acquiring twenty H145M medium-sized multi-mission military rotary-wing aircrafts and sixteen H225M long-range tactical transport military helicopters. The deal also contains a five-year logistical support, training and retraining programme. Still, the parties also agreed that Airbus would build a competence centre in Gyula, Hungary, to produce helicopter parts.[xxxviii] Two KC-390 jet-powered military transport aircrafts will arrive for the HDF from Brazil in 2024. Two used Airbus A319 jet airliners already have been deployed from Berlin in 2018.

Re-establishing the Hungarian military industry is also a primary goal of the programme, which means that "Hungarians give Hungarian weapons to Hungarian soldiers".[xxxix] P-07 and P-09 type pistols, BREN 2 type assault rifles and SCORPION EVO 3 type submachine guns were manufactured in Hungary after agreeing with the Czech Ceská Zbrojovka Export (CZ) company in 2018. Dynamic Nobel Defence GmbH will establish a unit in Hungary's Kiskunfélegyháza to research and produce explosive reactive armours and anti-armour grenade weapons. The German Rheinmetall will also build explosives and large-calibre ammunition, grenades and mortar manufacturing plants in Hungary.[xl]

Six years of intense development and modernisation passed, and the “Zrínyi 2026” programme is now in its second phase. The following years were expected to be the years of training and learning for soldiers receiving a more advanced, new military technology. And Hungary finally could get rid of its outworn armaments. The goal of the “Zrínyi 2026” regarding the size of the HDF is to increase the number of operational staff to 37,650 (currently, it is 34,200) and refill the Volunteer Reserve System with 20,000 personnel.[xli] In 2019, the government raised the level of ambition for the maximum number of Hungarian soldiers deployed on international missions from 1,000 to 1,200. Most HDF troops were deployed to Kosovo (KFOR, 472 people), Bosnia-Herzegovina (EU Op. Althea, 174 people) and Iraq (Operation Inherent Resolve, 138 people) in 2021.[xlii] Annual defence expenditure in 2022 is up to 1,000 billion, which means around 1.7% of the GDP, and in the same phase, the country is expected to reach the NATO requirement of 2% of military spending the following year.[xliii]

Hungary's new National Military Strategy was published in 2021, articulating one of the main goals, which is to make the Hungarian Defence Forces one of the most decisive forces in the region by 2030.[xliv] As a result of force development and modernisation, Hungary's self-defence capability has grown significantly, which is essential for self-defence and deterrence purposes and allows the country to remain an influential contributor to regional, European and transatlantic security efforts.[xlv]

Right in time

As it was mentioned before, the Hungarian force development and capacity building programme fits into the regional and European tendencies. The proliferation of terror attacks throughout Europe, the migration crisis and Russia’s assertive behaviour convinced governments to urgently increase their defence spending. But the United States’ strategic rebalancing as it shifts focus towards the Indo-Pacific region instead of Europe also indicates the vital need for the strategic independence of the European continent. Furthermore, Russia’s war on Ukraine that started on 24 February amplifies this need for accurate defence capacities and even closer cooperation within the existing alliances, including the EU and NATO. With Russia’s invasion, conventional war in Europe after a long-time became a reality again, and both the EU and the North Atlantic Alliance, including their individual member countries, had to have the appropriate response supported by an adequate capacity – including military power.

Hungarian NMS, published in 2021, focuses not only on non-conventional wars and non-state challenges but also contemplates the chance of a conventional war.[xlvi] The strategy articulates that the cornerstone of Hungary's security is the collective defence provided within the framework of NATO, but for this, independent self-defence and deterrence capabilities are also vital. And Hungary acts according to this principle during the ongoing war in its neighbourhood. Hungary works closely with its allies in both the EU and NATO, including allowing the entry of NATO forces into the country and arms shipments through its territory to other EU countries. However, the government rejects direct arms shipments to Ukraine through Hungary’s territory neither does it support sanctions on essential Russian energy.[xlvii] NATO has decided to strengthen its eastern flank by deploying troops in the form of battlegroups to additional four Eastern European countries, including Hungary. The battlegroup consisted mainly of soldiers of the HDF, but the United States, Turkey, Croatia, Montenegro and Italy also voiced their intention to join the Hungarian Battalion.[xlviii] In March, HDF soldiers, in cooperation with US troops, started a military exercise named “Eastern Shield 2022” near the Hungarian-Ukrainian borders.[xlix] That our world, including the European security architecture, will no longer be what it was before the Russian-Ukraine war is certain. This new situation must be taken into consideration in force development and strategy-making processes. As a consequence of the war, Hungary’s role in the EU and even more in NATO is likely to be valorised, which means closer cooperation with the Alliance in the form of joint exercises, training and international contingents in the country but joint procurements and capacity building are also probable. The sharing of know-how and the selling of cutting-edge military technology on a larger scale by countries like the US is also liable, which could positively impact the developing Hungarian military industry, which is unlikely to be a neglected sector anymore.

Conclusion

In the 1990s, after the regime change, Hungary had not just the opportunity but the need for a profound transformation of its military. Let alone the gradual reduction of the size of the Hungarian Defence Forces was carried out in the 1990s, no reform or modernisation which could have helped the HDF rid itself of the burdens of its Cold War past regarding structure and military technology occurred either.

However, Hungary’s accessions to the NATO and the EU were completed by 2004, without political will, and adequate budgetary resources the defence sector remained neglected for another decade. This meant gradually decreasing defence expenditure, delays in modernisation, gravely outdated technology and deteriorating morale in the HDF, while our mandatory contribution to NATO has also consistently been failing. Nevertheless, it should be emphasised that the country outperformed the EU, the OSCE and NATO in peacekeeping and crisis management missions for which the HDF gained international recognition.

Decreasing defence expenditure and the low priority of the security and defence sector as the consequence of the economic and financial crisis in 2008-2009 were global tendencies that Hungary fit perfectly. But by the mid-2010s, the Hungarian government devoted itself to carrying out an overall force development programme and to modernise the HDF. The deteriorating European security environment, in the face of terrorism, migration, and Russian interventionism, had given every reason for it. And the political continuity (the ruling party's victory in four constitutive elections) provided all the opportunity to make strategic, deep reforms in the HDF. Although the “Zrínyi 2026” force development programme is just halfway complete, Hungary's defence capability has grown significantly, which is essential not only for self-defence and deterrence purposes but also for the country to remain an influential contributor to regional, European and transatlantic security efforts in trying times.

Bibliography

34th 'László Bercsényi' Special Operations Battalion MH 34. Bercsényi László Különleges Muveleti Zászlóalj In: GlobalSecurity.org

https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/europe/hu-mh-34-blkmz.htm (25.05.2022)

A honvédség létszáma és a honvédek illetménye In: Képviselői Információs Szolgálat, Nov. 2014

A KORMÁNY 1393/2021 (VI. 24) határozata Magyarország Nemzeti Katonai Stratégiájáról In: Honvédelem, Dec. 2021

https://honvedelem.hu/hirek/nemzeti-katonai-strategia.html (25.05.2022)

A rendszerváltás évei Magyarországon In: Magyar Nemzeti Levéltár

https://mnl.gov.hu/mnl/ol/virtualis_kiallitas/a_rendszervaltas_evei_magyarorszagon (25.05.2022)

MÜLLER, Tamás: Honvédelmi Fejlesztések In: Képviselői Információs Szolgálat, 2020/64

BÉKEFI, Miklós: Kutatás a haderőfejlesztésről, In: SVKI, 2021

https://svkk.uni-nke.hu/hirek/2021/09/05/kutatas-a-haderofejlesztesrol (25.05.2022)

BUDAVÁRY, Krisztina: A Zrínyi 2026 program. Korlátozott lehetőségek a magyar védelmi ipar fejlesztésére In: Hadtudomány, 2019/3

http://real.mtak.hu/105874/1/2019eA%20Zr%C3%ADnyi%202026%20program_Budav%C3%A1ri%20Krisztina.pdf (25.05.2022)

CSIKI, Varga Tamás: A gazdasági válság hatása Magyarország és egyes szövetséges államok védelmi reformjaira és stratégiai tervezésére II In: NKE SVKK, 2013/10

CSIKI, Varga Tamás: A magyar védelmi kiadások trendjei, 2004–2019 In: Nemzet és Biztonság, 2019/1

https://folyoirat.ludovika.hu/index.php/neb/article/view/1280 (25.05.2022)

CSIKI, Varga Tamás: A védelmi kiadások regionális trendjei– Kelet-Közép-Európa In: SVKI Elemzések, 2021/17

http://www.mat.hu/hun/downloads/docs/svk_2021_17.pdf (25.05.2022)

DRAVECZKi-URI, Ádám: Zrínyi 2026 In: Honvédelem, Jan. 2017

https://honvedelem.hu/hirek/hazai-hirek/zrinyi-2026-2026.html (25.05.2022)

EGEBERG, Kristoffer: A constructive celebration In: SFOR Informer Online, February, 2001

https://www.nato.int/sfor/indexinf/107/s107p03b/t0102213b.htm (25.05.2022)

Enlargement and Article 10 In: NATO, May 2022

https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/topics_49212.htm (25.05.2022)

FITCHETT, Joseph: U.S. Is Moving Troops To Peacekeeping Duty From Ex-Soviet Site : NATO Base In Hungary Key Center For Bosnia In: New York Times, Oct. 1996

https://www.nytimes.com/1996/10/16/news/us-is-moving-troops-to-peacekeeping-duty-from-exsoviet-site-nato-base.html (25.05.2022)

HACKETT, James (ed.): The Military Balance 2022 – International Institute for Strategic Studies. Routledge, London, 2021, p. 115

JAKUS, János: A Magyar Honvédség a rendszerváltástól napjainkig In: Magyar Hadtudományi Társaság, 2005/1

https://www.mhtt.eu/hadtudomany/2005/1/2005_1_5.html (25.05.2022)

JÁRDI, Roland: Hamarabb teljesíthetjük a NATO-célt In: VG, Mar. 2022

https://www.vg.hu/vilaggazdasag-magyar-gazdasag/2022/03/hamarabb-teljesithetjuk-a-nato-celt (25.05.2022)

KATONA, András: A honvédelemről, a hadseregről szóló ismeretek tanításának módszertani kérdései In: Történelemtanítás, May 2010

Keleti Pajzs: Hazánk elkötelezett szövetséges In: Honvédelem, Mar. 2022

https://honvedelem.hu/hirek/keleti-pajzs-hazank-elkotelezett-szovetseges.html (25.05.2022)

KERN, Tamás: A rendszerváltás utáni haderőreformkísérletek, 2009 p. 7

http://www.szenzorkft.hu/public/files/documents/a_rendszervaltas_utani_haderoreform.pdf (25.05.2022)

KISS, Petra: A magyar stratégiai gondolkodás változása a nemzeti biztonsági stratégiák tükrében, In: Hadtudomány, 2012/3

https://www.mhtt.eu/hadtudomany/2012/3_4/HT_2012_3-4_Kiss_Petra.pdf (25.05.2022)

Military expenditure by country as percentage of gross domestic product, 1988-2020 In: SIPRI 2021

PM Orbán: “Together with Our EU and NATO Allies, We Condemn Russia’s Military Attack” In: Hungary Today, Feb. 2022

https://hungarytoday.hu/orban-russia-attack-condems-aggression/ (25.05.2022)

Press Info: The accession of the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland In: NATO, 1999

https://www.nato.int/docu/comm/1999/9904-wsh/pres-eng/03acce.pdf (25.05.2022)

PUNGOR, András: „Egyre rosszabb helyzetbe hozták a haderőt a rendszerváltás utáni kormányok” In: 168 óra, July 2017

https://168.hu/itthon/egyre-rosszabb-helyzetbe-hoztak-a-haderot-a-rendszervaltas-utani-kormanyok-152560 (25.05.2022)

SAJÓ, Dávid: Magyar emberek magyar fegyvert adnak magyar katonák kezébe In: Index, July, 2017

https://index.hu/belfold/2018/07/05/nogradi_nemeth_szilard_honvedelem_martos/ (25.05.2022)

SZENES, Zoltán: Koncepcióváltás a magyar békefenntartásban? In: Nemzet és Biztonság, Apr. 2008

http://www.nemzetesbiztonsag.hu/cikkek/szenes_zoltan-koncepciovaltas_a_magyar_bekefenntartasban_.pdf (25.05.2022)

SZENES, Zoltán: Magyar haderő-átalakítás a NATO-tagság idején In: Nemzet és Biztonság, April 2009

http://www.nemzetesbiztonsag.hu/cikkek/szenes_zoltan-magyar_hader___atalakitas_a_nato_tagsag_idejen.pdf (25.05.2022)

The Wales Declaration on the Transatlantic Bond In: NATO, Sept. 2014

https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_112985.htm (25.05.2022)

VASKI, Tamás: What Is a Battlegroup? NATO Troops Set to Deploy into Western Hungary In: Hungary Today, Mar, 2022

https://hungarytoday.hu/nato-battlegroup-hungary/ (25.05.2022)

WAGNER, Péter: Az amerikai terrortámadások hatása a Magyar Honvédségre In: Nemzet és Biztonság, Oct. 2011

http://www.nemzetesbiztonsag.hu/cikkek/wagner_peter-9_11_es_a_magyar_honvedseg.pdf (25.05.2022)

WALLANDER, Caleste A. : NATO’s Price: Shape Up or Ship Out In: Foreign Affairs, Dec. 2002

https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/2002-11-01/natos-price-shape-or-ship-out?check_logged_in=1 (25.05.2022)

Endnotes

[i] WALLANDER, Celeste A. : NATO’s Price: Shape Up or Ship Out In: Foreign Affairs, Dec. 2002

https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/2002-11-01/natos-price-shape-or-ship-out?check_logged_in=1 (25.05.2022)

[ii] A rendszerváltás évei Magyarországon In: Magyar Nemzeti Levéltár

https://mnl.gov.hu/mnl/ol/virtualis_kiallitas/a_rendszervaltas_evei_magyarorszagon (25.05.2022)

[iii] SZENES, Zoltán: Magyar haderő-átalakítás a NATO-tagság idején In: Nemzet és Biztonság, April 2009

http://www.nemzetesbiztonsag.hu/cikkek/szenes_zoltan-magyar_hader___atalakitas_a_nato_tagsag_idejen.pdf (25.05.2022)

[iv] KATONA, András: A honvédelemről, a hadseregről szóló ismeretek tanításának módszertani kérdései In: Történelemtanítás, May 2010

[v] KATONA, András: A honvédelemről, a hadseregről szóló ismeretek tanításának módszertani kérdései In: Történelemtanítás, May 2010

[vi] KERN, Tamás: A rendszerváltás utáni haderőreformkísérletek, 2009 p. 7

http://www.szenzorkft.hu/public/files/documents/a_rendszervaltas_utani_haderoreform.pdf (25.05.2022)

[vii] SZENES, Zoltán: Magyar haderő-átalakítás a NATO-tagság idején In: Nemzet és Biztonság, April 2009

http://www.nemzetesbiztonsag.hu/cikkek/szenes_zoltan-magyar_hader___atalakitas_a_nato_tagsag_idejen.pdf (25.05.2022)

[viii] KATONA, András: A honvédelemről, a hadseregről szóló ismeretek tanításának módszertani kérdései In: Történelemtanítás, May 2010

[ix] JAKUS, János: A Magyar Honvédség a rendszerváltástól napjainkig In: Magyar Hadtudományi Társaság, 2005/1

https://www.mhtt.eu/hadtudomany/2005/1/2005_1_5.html (25.05.2022)

[x] ENGELBERG, Kristoffer: A constructive celebration In: SFOR Informer Online, February 2001

https://www.nato.int/sfor/indexinf/107/s107p03b/t0102213b.htm (25.05.2022)

[xi] FITCHETT, Joseph: US. Is Moving Troops To Peacekeeping Duty From Ex-Soviet Site : NATO Base In Hungary Key Center For Bosnia In: New York Times, Oct. 1996

https://www.nytimes.com/1996/10/16/news/us-is-moving-troops-to-peacekeeping-duty-from-exsoviet-site-nato-base.html (25.05.2022)

[xii] Press Info: The accession of the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland In: NATO, 1999

https://www.nato.int/docu/comm/1999/9904-wsh/pres-eng/03acce.pdf (25.05.2022)

[xiii] SZENES, Zoltán: Magyar haderő-átalakítás a NATO-tagság idején In: Nemzet és Biztonság, April 2009

http://www.nemzetesbiztonsag.hu/cikkek/szenes_zoltan-magyar_hader___atalakitas_a_nato_tagsag_idejen.pdf (25.05.2022)

[xiv] JAKUS, János: A Magyar Honvédség a rendszerváltástól napjainkig In: Magyar Hadtudományi Társaság, 2005/1

https://www.mhtt.eu/hadtudomany/2005/1/2005_1_5.html (25.05.2022)

[xv] SZENES, Zoltán: Magyar haderő-átalakítás a NATO-tagság idején In: Nemzet és Biztonság, April 2009

http://www.nemzetesbiztonsag.hu/cikkek/szenes_zoltan-magyar_hader___atalakitas_a_nato_tagsag_idejen.pdf (25.05.2022)

[xvi] KERN, Tamás: A rendszerváltás utáni haderőreformkísérletek, 2009 p. 7

http://www.szenzorkft.hu/public/files/documents/a_rendszervaltas_utani_haderoreform.pdf (25.05.2022)

[xvii] WALLANDER, Celeste A. : NATO’s Price: Shape Up or Ship Out In: Foreign Affairs, Dec. 2002

https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/2002-11-01/natos-price-shape-or-ship-out?check_logged_in=1 (25.05.2022)

[xviii] Enlargement and Article 10 In: NATO, May 2022

https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/topics_49212.htm (25.05.2022)

[xix] KISS, Petra: A magyar stratégiai gondolkodás változása a nemzeti biztonsági stratégiák tükrében, In: Hadtudomány, 2012/3

https://www.mhtt.eu/hadtudomany/2012/3_4/HT_2012_3-4_Kiss_Petra.pdf (25.05.2022)

[xx] SZENES, Zoltán: Magyar haderő-átalakítás a NATO-tagság idején In: Nemzet és Biztonság, April 2009

http://www.nemzetesbiztonsag.hu/cikkek/szenes_zoltan-magyar_hader___atalakitas_a_nato_tagsag_idejen.pdf (25.05.2022)

[xxi] KATONA, András: A honvédelemről, a hadseregről szóló ismeretek tanításának módszertani kérdései In: Történelemtanítás, May 2010

[xxii] KATONA, András: A honvédelemről, a hadseregről szóló ismeretek tanításának módszertani kérdései In: Történelemtanítás, May 2010

[xxiii] 34th 'László Bercsényi' Special Operations Battalion MH 34. Bercsényi László Különleges Muveleti Zászlóalj In: GlobalSecurity.org

https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/europe/hu-mh-34-blkmz.htm (25.05.2022)

[xxiv] WAGNER, Péter: Az amerikai terrortámadások hatása a Magyar Honvédségre In: Nemzet és Biztonság, Oct. 2011

http://www.nemzetesbiztonsag.hu/cikkek/wagner_peter-9_11_es_a_magyar_honvedseg.pdf (25.05.2022)

[xxv] SZENES, Zoltán: Koncepcióváltás a magyar békefenntartásban? In: Nemzet és Biztonság, Apr. 2008

http://www.nemzetesbiztonsag.hu/cikkek/szenes_zoltan-koncepciovaltas_a_magyar_bekefenntartasban_.pdf (25.05.2022)

[xxvi] CSIKI, Varga Tamás: A magyar védelmi kiadások trendjei, 2004–2019 In: Nemzet és Biztonság, 2019/1

https://folyoirat.ludovika.hu/index.php/neb/article/view/1280 (25.05.2022)

[xxvii] CSIKI, Varga Tamás: A magyar védelmi kiadások trendjei, 2004–2019 In: Nemzet és Biztonság, 2019/1

https://folyoirat.ludovika.hu/index.php/neb/article/view/1280 (25.05.2022)

[xxviii] A gazdasági válság hatása Magyarország és egyes szövetséges államok védelmi reformjaira és stratégiai tervezésére II In: NKE SVKK, 2013/10

[xxix] A honvédség létszáma és a honvédek illetménye In: Képviselői Információs Szolgálat, Nov. 2014

[xxx] CSIKI, Varga Tamás: A magyar védelmi kiadások trendjei, 2004–2019 In: Nemzet és Biztonság, 2019/1

https://folyoirat.ludovika.hu/index.php/neb/article/view/1280 (25.05.2022)

[xxxi] CSIKI, Varga Tamás: A védelmi kiadások regionális trendjei– Kelet-Közép-Európa In: SVKI Elemzések, 2021/17

http://www.mat.hu/hun/downloads/docs/svk_2021_17.pdf (25.05.2022)

[xxxii] CSIKI, Varga Tamás: A védelmi kiadások regionális trendjei– Kelet-Közép-Európa In: SVKI Elemzések, 2021/17

http://www.mat.hu/hun/downloads/docs/svk_2021_17.pdf (25.05.2022)

[xxxiii] Military expenditure by country as a percentage of gross domestic product, 1988-2020 In: SIPRI 2021

[xxxiv] The Wales Declaration on the Transatlantic Bond In: NATO, Sept. 2014

https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_112985.htm (25.05.2022)

[xxxv] PUNGOR, András: „Egyre rosszabb helyzetbe hozták a haderőt a rendszerváltás utáni kormányok” In: 168 óra, July 2017

https://168.hu/itthon/egyre-rosszabb-helyzetbe-hoztak-a-haderot-a-rendszervaltas-utani-kormanyok-152560 (25.05.2022)

[xxxvi] DRAVECZKi-URI, Ádám: Zrínyi 2026 In: Honvédelem, Jan. 2017

https://honvedelem.hu/hirek/hazai-hirek/zrinyi-2026-2026.html (25.05.2022)

[xxxvii] B: MÜLLER, Tamás Honvédelmi Fejlesztések In: Képviselői Információs Szolgálat, 2020/64

[xxxviii] JÁRDI, Roland: Hamarabb teljesíthetjük a NATO-célt In: VG, Mar. 2022

https://www.vg.hu/vilaggazdasag-magyar-gazdasag/2022/03/hamarabb-teljesithetjuk-a-nato-celt (25.05.2022)

[xxxix] SAJÓ, Dávid: Magyar emberek magyar fegyvert adnak magyar katonák kezébe In: Index, July, 2017

https://index.hu/belfold/2018/07/05/nogradi_nemeth_szilard_honvedelem_martos/ (25.05.2022)

[xl] BUDAVÁRY, Krisztina: A Zrínyi 2026 program. Korlátozott lehetőségek a magyar védelmi ipar fejlesztésére In: Hadtudomány, 2019/3

http://real.mtak.hu/105874/1/2019eA%20Zr%C3%ADnyi%202026%20program_Budav%C3%A1ri%20Krisztina.pdf (25.05.2022)

[xli] HACKETT, James (ed.): The Military Balance 2022 – International Institute for Strategic Studies. Routledge, London, 2021, p. 115

[xlii] HACKETT, James (ed.): The Military Balance 2022 – International Institute for Strategic Studies. Routledge, London, 2021, p. 115

[xliii] JÁRDI, Roland: Hamarabb teljesíthetjük a NATO-célt In: VG, Mar. 2022

https://www.vg.hu/vilaggazdasag-magyar-gazdasag/2022/03/hamarabb-teljesithetjuk-a-nato-celt (25.05.2022)

[xliv] BÉKEFI, Miklós: Kutatás a haderőfejlesztésről, In: SVKI, 2021

https://svkk.uni-nke.hu/hirek/2021/09/05/kutatas-a-haderofejlesztesrol (25.05.2022)

[xlv] A KORMÁNY 1393/2021 (VI. 24) határozata Magyarország Nemzeti Katonai Stratégiájáról In: Honvédelem, Dec. 2021

https://honvedelem.hu/hirek/nemzeti-katonai-strategia.html (25.05.2022)

[xlvi] A KORMÁNY 1393/2021 (VI. 24) határozata Magyarország Nemzeti Katonai Stratégiájáról In: Honvédelem, Dec. 2021

https://honvedelem.hu/hirek/nemzeti-katonai-strategia.html (25.05.2022)

[xlvii] PM Orbán: “Together with Our EU and NATO Allies, We Condemn Russia’s Military Attack” In: Hungary Today, Feb. 2022

https://hungarytoday.hu/orban-russia-attack-condems-aggression/ (25.05.2022)

[xlviii] VASKI, Tamás: What Is a Battlegroup? NATO Troops Set to Deploy into Western Hungary In: Hungary Today, Mar, 2022

https://hungarytoday.hu/nato-battlegroup-hungary/ (25.05.2022)

[xlix] Keleti Pajzs: Hazánk elkötelezett szövetséges In: Honvédelem, Mar. 2022

https://honvedelem.hu/hirek/keleti-pajzs-hazank-elkotelezett-szovetseges.html (25.05.2022)