Research / Geopolitics

Swedish neutrality: How long can it last?

While neutrality for Sweden was initially more of a pragmatic decision, it solidified into an identity as it preserved the country from drifting into the World Wars and the conflicts of the bipolar world order in the 20th century. A long-cherished identity, the two-century long successive policy, the third, “Swedish way” that seemed to be unchangeable for many decades may just change as the threat of Russian expansion has become a predictive sign and a reality more than ever for the Swedes too, after Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022.

The evolution of the Swedish neutrality

The origins of Swedish neutrality

In the beginning of the 19th century Sweden’s role as a regional great power in Scandinavia and in the Baltics had come to an end. In the Napoleonic wars (1803-1815) Sweden lost over a third of its territory including the Åland Islands and the whole of Finland to the Russians. Subsequently, Sweden participated in the coalition against Napoleon in 1813.[1] The King of Sweden Charles XIII recognised Finland as Russian territory, in return the Tsar helped him in pressuring Denmark to give Norway up to Sweden. Sweden turned against Denmark, which was forced to surrender Norway in the Peace of Kiel (14 January 1814). As Norway resisted Swedish hegemony and wanted independence the Swedish heir to the throne Jean Baptiste Jules Bernadotte (former general of Napoleon, later known as Charles XIV John) invaded Norway. After the Swedish invasion a personal union between Sweden and Norway was formed in November 1814.[2]

These episodes in Sweden’s history are key moments to understand the monarchy and its posture in international affairs for the following decades until today for two reasons. One is that as the result of these wars the borders of Sweden known today were formed. Second, since these wars, Sweden has not taken part in any armed conflict following the policy of neutrality and non-alignment.

Neutrality was adopted by Sweden in the aftermath of the grave loss of Finland, however the policy of neutrality did not take affect de facto in the following years until the Treaty of Kiel (1914). Although the 19th century saw many additional regional wars (e.g., First and Second War of Schleswig; Crimean War) Sweden managed to remain neutral and strengthen itself in the policy of neutrality. But in the meantime, Sweden did not intend to drift into a vulnerable, helpless position in the name of neutrality. Swedish Minister for Foreign Affairs from this period, Christofer Rutger Ludvig Manderström articulated the precept of Sweden as "to go their way in quiet and calm"[3] It meant defence spending and capacity development not for foreign conquest or adventure but for self-defence. And this mindset then characterised the Swedish policy of neutrality throughout.

The consolidation of neutrality during the World Wars

Solidification of the policy of neutrality helped Sweden not to get involved in the First World War. Despite the pro-German bias of the Swedish government and Queen Victoria herself, a unanimous parliamentary support stood up for a declaration of neutrality in the global conflict. Although Swedish foreign trade was under great pressure from both belligerent blocs, Sweden became economically and politically stronger and more determined in the policy of political-military neutrality. After the World War and extensive parliamentary debates Sweden joined the League of Nations which resulted in the practice of an "active policy of neutrality". The final reason of the country joining the League of Nations was the assessment of the international organisation as culturally modern and working for peace – considered a tradition by the Swedes. In this spirit of strengthening peace Sweden for example accepted the decision of the League of Nations with regards to the Åland Islands remaining under Finland’s sovereignty and to keep it a demilitarised territory. And by the influence of those who were concerned that joining the League of Nations would undermine the policy of neutrality, the Swedish government declared that Sweden did not perceive itself obligated to partake in any military sanctions.

After the outbreak of the Second World War Sweden immediately declared its neutrality and non-alignment and sought to forge a bloc of neutral, non-committed countries including Belgium, the Netherlands, Denmark, Norway, Finland and the Baltic States. But Sweden was forced to change its approach immediately as its regional situation changed. After the Soviet Union attacked Finland in November 1939 Sweden declared itself a non-belligerent party and began to support the Finns' fight against the Soviets with ammunition, weapons and munitions besides allowing more than 8,000 Swedish volunteers to fight in Finland.[4]

But with the occupation of Denmark and Norway by the Germans, and Finland’s battle with the Soviet forces, the war just came to the doorstep of Stockholm and the chance of Sweden’s military occupation became a rough reality. Being aware of the German threat, Sweden declared strict neutrality to avoid the fate of Denmark and Norway. It indicated that the ideological and cultural kinship or previous political cooperation with the Scandinavian states were overcome by a realpolitik approach, when Sweden’s security and defence interests came to the fore for the sake of preventing the country from drifting into war or even from becoming occupied.[5]

Assessing Sweden’s balancing foreign policy from this period is more than ambiguous as on the one hand it supported the Norwegian resistance movement, facilitated the escape of 8,000 Danish Jews to Sweden, received 35,000 Baltic refugees and helped to place 70,000 Finnish children with foster parents.[6] But on the other hand it let the Germans use its territory, airspace and territorial waters for troop movements and made concessions to Germany that could continuously export Swedish iron ore to feed its arm industry. Despite this balancing policy of neutrality divided the political leadership and the society of Sweden (the latter was more sympathetic with the Allies; while the former – including King Gustaf V and the majority of the Swedish army officers – was more pro-German) and the small room left for political manoeuvring Sweden managed to remain neutral until the end of the Second World War. The policy of neutrality bore its fruit for Sweden as the country was left out from the world wars and their devastating social, economic, infrastructural consequences which just solidified and justified the country to stay along this path further.

Neutrality as an identity during the Cold War

After the Second World War during the geopolitical changes and the consolidation of the bipolar world order Sweden intended to find its place in the regional context and international arena. One of its examples was the idea of a neutralist Scandinavian defence union which would have resulted in the coordination of the foreign and defence policies of Sweden, Norway and Denmark. The security cooperation would have remained under the countries’ national sovereignty but would have required common acts and decisions as a bloc in security issues. But by 1949, western countries – including Denmark and Norway as founding members – turned to a broader, Euro-Atlantic security cooperation, namely the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) to deter the Soviet Union. This way the intercontinental NATO has superseded the regional initiative of the Scandinavian defence union.

In the shadow of the NATO and the Warsaw Pact (WP) Sweden decided to remain by the well-tried policy of neutrality and non-alignment. Although it also strived to develop adequate military capacity to resist a possible military aggression from other countries (mainly from the WP). This capacity building included increasing the defence spending, maintaining general conscription, becoming partly self-sufficient in military technology and even pursuing an independent nuclear weapon programme (which was soon abandoned in the 50s). All these measures resulted in the fact that despite neutrality the Swedish military contained 850,000 personnel (after mobilisation) with self-produced fighter-jets, submarines, tanks and the fourth largest air force in the world during the Cold War.[7]

Sweden refrained from joining any political or military alliances and organisations which they saw could jeopardize the county’s neutral status in the eyes of the international community, however deepening ties with the US and NATO countries clearly bounded it to the West, it was even involved in intelligence operations.[8]

Stockholm also joined such organisations and forums which it believed could reconcile with the policy of neutrality. Sweden joined the United Nations in 1949, it initiated the Nordic Council (a platform for inter-parliamentary cooperation among Nordic countries) in 1952 and became a member of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) in 1960.[9] Joining these organisations indicates that even while Sweden pursued to promote the “third-way” Swedish model in the bipolar world it also made it obvious that the country’s identity stands not only on neutrality but also on belonging to the West. And this unanimous identity marked Sweden’s further path to Western integration after the Cold War too.

In summary, the interpretation of the Swedish neutrality policy during the Cold War has two major views. The first is a general view that Sweden’s neutrality aimed at easing tension in peacetime and to keep the country (located between east and west) out of a new major – in worst case scenario even a nuclear – war. The second view is that neutrality would have never worked in time of a war looking at Sweden’s geopolitical position. “Sweden would then either have been attacked by the USSR because it was a Western country in its path of attack, or it would have been drawn in on the allied side because of its cooperation with the West, including tolerating overflights by allied bombers.”[10] To conclude, during the Cold War era Sweden stuck to the policy of neutrality, as the country saw it as the proven and the best way to preserve its integrity and to promote its security.

Eroding Swedish neutrality

Sweden in the European Union

When Sweden joined the European Union in 1995 its incentives to do so were solely economic.[11] Developing an extensive welfare-state system was a core element of the “Swedish model” but inter alia erroneous economic policy decisions and international recession resulted in a fiscal crisis in the beginning of the 90s.[12] Sweden's GDP declined by around 5% while the central bank increased interest rates to 500% to defend the Swedish krona from devaluation.[13] To preserve the Swedish welfare state – seen partly as the benefit from neutrality in wartime – and to improve Sweden’s competitiveness, EU membership was seen to be an inevitable step for the country. Which it certainly took in 1995 after a referendum passed with 52.3% in favour of joining the EU.[14] But spill over effects in the EU soon began to expand the scope of its policies from the economic sphere to other areas and required deeper integration from the members. And this deeper integration started to erode and hollow out Sweden’s strict policy of neutrality.

Swedish neutrality became even more questionable after the Treaty of Lisbon which inter alia intended to strengthen solidarity between EU member states. The Mutual Defence Clause (Article 42.7 of the Treaty on European Union) declares: “If a Member State is the victim of armed aggression on its territory, the other Member States shall have towards it an obligation of aid and assistance by all the means in their power, in accordance with Article 51 of the United Nations Charter.”[15] And however, the text also articulates that the clause “shall not prejudice the specific character of the security and defence policy of certain Member States” – which is believed to have been addressed to neutral or non-aligned EU member states as an opportunity to opt-out in case of an attack – it still raises the question how Sweden could be a member of the EU with a mutual defence clause and uphold its neutral status effectively at the same time.[16]

In the same year, (along with the EU’s Mutual Defence Clause and Solidarity Clause (Article 222 TFEU)) Swedish parliament adopted a declaration of solidarity with the EU and other Nordic states (as Norway and Iceland are not members of the bloc). The declaration - which is now an integral part of the Swedish security strategy - states that Sweden will not remain passive in a scenario when another EU Member State or Nordic country suffers a disaster or an attack, including giving them military support.[17] Sweden also expects from these countries to do the same for them.[18] This solidarity declaration is interpreted as a complete abandonment of the policy of neutrality by some experts.[19]

Even if Sweden is reluctant to foster a European Defence Union and to support intergovernmental cooperation instead of centralisation when it comes EU security and defence policy, the country’s involvement in several EU defence cooperation and missions further challenges the country’s claim on still being neutral. Swedish peacekeeping troops are deployed for training purposes in different EU missions including the Central African Republic (EUTM RCA), Mali (EUTM Mali) and Somalia (EUTM Somalia).[20] Sweden also supports the civil dimension of the EU’s Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) the Civilian CSDP Compact, it participates in six projects under the EU’s Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) while observes other eleven. Sweden has joined eight projects under the European Defence Fund (EDF) and participated in the EU’s Nordic Battlegroup which was ready on operation in 2008 and in 2011 and consisted of around 2,500 multinational soldiers.[21]

Sweden and the NATO

Despite Sweden’s deepening EU integration and defence cooperation with member states the country still defines neutrality as a core of its identity. This long-cherished identity would unambiguously and undeniably change if Sweden joined the NATO. In other words: the last factor indicating Sweden’s neutrality and non-alignment is the fact that it has not joined NATO yet. By joining, Sweden would also shut the last leeway to be neutral in a possible war. But despite all of this it does not mean that Sweden has not made several efforts to enhance its military cooperation with the alliance.

In 1994 Sweden joined the NATO Partnership for Peace (PfP) programme which allows bilateral practical cooperation between non-NATO nations and the organisation along certain issues and priorities.[22]The accession also brought economic benefits for the country as Swedish military and automotive factories became active suppliers in the armaments of the newly independent Balkan states, but Swedish military equipment also appeared to be an alternative for Eastern European countries too in modernising their military.

Downsizing and dismantling of the Swedish Armed Forces started in parallel with the country’s EU and NATO PfP accession. Army transformation was focused on forming such forces which are appropriate to carry out expeditionary and peacekeeping missions for the United Nations, the European Union or the NATO.

Sweden’s participation in NATO’s foreign missions - even with more willingness than some NATO countries - also indicates the country’s deep cooperation with the defence alliance. Swedish troops were represented in Bosnia (IFOR and SFOR), Kosovo (KFOR), Afghanistan (ISAF) and Libya (Operation Unified Protector). Despite the latter divided even NATO members, as such countries as Germany, Poland, Spain and Turkey did not participate, Sweden got on NATO’s board.[23] In addition Sweden is also participating in the alliance’s multinational quick response corps, the NATO Response Force (NRF) and in 2016 Sweden ratified NATO Host Nation Support Agreement (HNS) which gives access to NATO to operate on Swedish territory during training or in the event of a conflict with the coordination of the host country.[24]

In or out?

Sweden seemingly wants to be as integrated and interoperable with NATO as possible, without being a member. It leaves open the possibility of both staying away and a quick joining of the alliance if the country’s interests and security situation require it in case of the eruption of a war. Generally, it could be said about the Swedish political leadership that the left wing, including the Social Democratic Party, the Green Party, the Left Party and the Sweden Democrats oppose the country joining the NATO, drawing on the country’s independence, autonomy and historical non-alignment policy. While right-wing and centrist parties such as the Moderate Party, the Centre Party, the conservative Christian Democrats, the Liberal Party are in favour of NATO membership to strengthen and guarantee Sweden’s security and defence as the country’s armed forces focused more on peacekeeping than self-defence tasks in the last decades.[25]

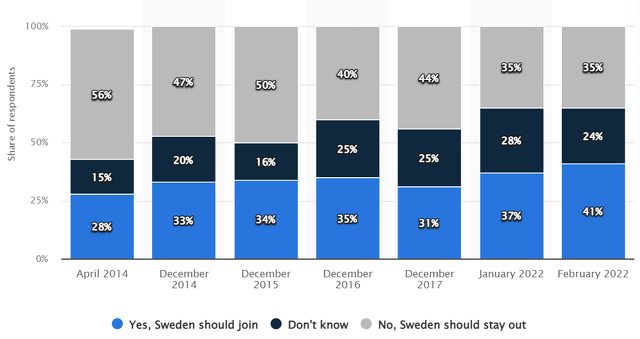

Swedish public opinion on joining the NATO has significantly changed and shifted in the last decade (see chart below). And the reason for that is the diffusion of serious threats jeopardising the security and stability of European countries or even the continent. Since the 2010s Europe has been increasingly facing such threats and attacks on its soil which it had not experienced for decades. On one hand non-state actors such as terror organisations and lone terrorists carried out several attacks that challenged Europe’s security and it - believed to be undisturbed - way of life (e.g., Norway 2011, Paris 2015, Nice, Brussels and Berlin 2016, Barcelona and Manchester 2017, Vienna 2020).

Figure 1: Swedes’ answer to the question: “Do you think Sweden should join the military alliance NATO?” (Source: Statista[26])

On the other hand, state actors’ assertive or even aggressive acts also became a reality today in Europe that makes the EU and the Euro-Atlantic bloc to corral and to seek joint response. And certainly, the perception of a possible assertive state’s actions is the main driver for the public (and for the political leadership) of the neutral Sweden to change its view on joining the NATO for the sake of security and defence.

During February and March 2014 Russia invaded the Crimean Peninsula and annexed it from Ukraine. In April 2014 demonstrations by pro-Russian groups and clashes between Russian-backed separatists and the Ukrainian military in the Donbas region of Ukraine escalated into a war. The war settled into a stalemate between Ukrainian military and the Russian-backed separatists assisted by Russian troops in the self-declared Donetsk and Luhansk republics.[27]

The armed annexation of Crimea and Russian penetration into East-Ukraine prompted deep concerns in the Baltics and Nordic countries fearing Russia’s expansionism would eventually reach them as well. And the fear from Russian interventionism and expansionism made a remarkable change already in 2014 in the Swedish public opinion on joining the NATO (see above) as the opposers’ camp shrank to 47% from 56% and those who favoured gained 5%.

And Sweden's concerns of Russian interventionism do not seem unfounded at all considering Russia’s repeated violation of the Swedish airspace and territorial waters in the last years. A mysterious – believed to be Russian - submarine in waters around Stockholm caused a huge military mobilisation and hunt in 2014.[28] In 2020 an extensive military activity in the Baltic Sea conducted by Russia prompted high readiness from the Swedish military and troop deployment to Gotland after Russian warships sailed close to the island.[29]

But the Kremlin also tested Sweden’s resolve by violations of its airspace several times: in 2013 Russian military aircrafts performed a training mission over Swedish Gotska Sandön island to which Sweden was unable to react either in time or without NATO’s help.[30] NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg in his 2015 annual report stated that the Russian jets simulated nuclear attacks on NATO and its partners. The following year, in 2014, there were ten Russians registered violations in Sweden.[31] These violations and threats certainly drove Sweden (and Finland) towards NATO.

Referring to the ongoing full-scale invasion of Ukraine by Russian forces the following can be said: Russia’s war on Ukraine that started on 24 February not just unified the North-Atlantic countries and the European Union in their response to Russian aggression but it caused a notable shift in Sweden’s public support for joining the NATO (see above). Both the opposers’ and the “unsure” base have shrunk in the last years and especially months indicating that a higher percentage (41%) is supporting Sweden to join the alliance than those who oppose (35%). And Sweden does not only have indirect reasons for reassessing its neutral position. Besides the direct Russian provocations and violations mentioned above Sweden has also been threatened by Russia both by verbal and by provocative military activities since the outbreak of the war. Two Russian SU27 and two SU24 fighter jets briefly entered Swedish airspace above Gotland Island in the Baltics on 2 March 2022.[32] While Russia's Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Maria Zakharova warned Finland and Sweden that their accession to NATO would have "serious military-political repercussions" which is a serious blowback pushing the country towards the NATO more than ever.[33]

Conclusion

The policy of neutrality came to Sweden from a realpolitik realisation of the country’s capability and geopolitical position. Even if the country is on the northern periphery of Europe it is located in the buffer zone between the East and the West which exposed it to the eternal war between the two poles. In the Napoleonic wars as Sweden lost over a third of its territory, it realised it had no more sufficient military capacity to preserve its political and territorial integrity as a buffer state. Therefore, for its own survival the country has chosen to seek and develop the policy of neutrality. As this policy has helped Sweden to keep away from World Wars and their disastrous social and economic effects neutrality and non-alignment not just solidified in the country but became an identity of the Swedish people and political leadership during the Cold War era.

But the Swedish neutrality was never meant to be a strict and passive neutrality policy. First, Sweden has always sought to have the adequate military capability to defend itself in case of a war and/or in case if its neutrality would be disrespected. Second, under the policy of neutrality and non-alignment Stockholm always allowed itself to manoeuvre in accordance with its interests and values. This flexible approach gave the country the opportunity to remain on the “Western” track and to integrate to the Western institution system in line with its neutrality during the Cold War.

After the fall of the Iron Curtain Sweden intended to keep the neutral orientation of its foreign and security policy but economic, political and security changes in the domestic, European and international arena have inclined the country to take cautious but continuous steps away from its tradition of neutrality. As a member of the European Union and high contributor of the bloc’s security- defence- and foreign policy initiatives including EU peace keeping missions the existence of Swedish neutrality in practice is highly questionable. And however, Sweden still sees neutrality as the core of its identity its continuous but careful steps slowly towards NATO erodes the reality of this identity. But the complete abandonment of neutrality would unanimously be the Swedish accession to the North-Atlantic organisation - which also seems more likely than ever as the effect of the current international events.

Bibliography

ÅSELIUS, Gunnar: Swedish Strategic Culture after 1945 In: JStor, 2005

https://www.jstor.org/stable/45084413 (09.03.2022)

Current International Missions In: Swedish Armed Forces, February, 2020

https://www.forsvarsmakten.se/en/activities/current-international-missions/ (09.03.2022)

DALSJÖ, Robert: The hidden rationality of Sweden's policy of neutrality during the Cold War In: Taylor&Francis Online, Apr, 2013

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14682745.2013.765865 (09.03.2022)

Do you think Sweden should join the military alliance NATO? In: Statista, 2022

https://www.statista.com/statistics/660842/survey-on-perception-of-nato-membership-in-sweden/ (09.03.2022)

DUXBURY, Charles: Sweden Ratifies NATO Cooperation Agreement In: Atlantic Council, May, 2016

https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/natosource/sweden-ratifies-nato-cooperation-agreement/ (09.03.2022)

DUXBURY, Charlie: Sweden edges closer to NATO membership In: Politico, December, 2020

https://www.politico.eu/article/sweden-nato-membership-dilemma/ (09.03.2022)

EAKIN, Hugh: The Swedish Kings of Cyberwar In: The New York Review, January, 2017

https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2017/01/19/the-swedish-kings-of-cyberwar/ (09.03.2022)

ELIASSON, Johan: Traditions, Identity and Security: The Legacy of Neutrality in Finnish and Swedish Security Policies in Light of European Integration In: Research Gate, June, 2004

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/5014999_Traditions_Identity_and_Security_The_Legacy_of_Neutrality_in_Finnish_and_Swedish_Security_Policies_in_Light_of_European_Integration (09.03.2022)

Ett användbart försvar - Regeringens proposition, 2008

https://www.regeringen.se/49bb67/contentassets/1236f9bd880b495f8a9dd94ce1cb71de/ett-anvandbart-forsvar-prop-200809140 (09.03.2022)

GäRTNER, Heinz: Engaged Neutrality: The Persistence of Neutrality in Post-Cold War Europe In: An Evolved Approach to the Cold War, 2002

https://books.google.hu/books?id=SsUpDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA89&lpg=PA89&dq=sweden+abandon+neutrality+%222002%22&source=bl&ots=oVZ1jFfnUw&sig=ACfU3U2eVpSxCe0KoGRtqMwWu6VdWsLScw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjEuNfWtKf2AhVIwQIHHRcJAsIQ6AF6BAgNEAM#v=onepage&q=sweden%20abandon%20neutrality%20%222002%22&f=false (09.03.2022)

GÖTZ, Norbert: Neutrality and the Nordic countries In: Nordics Info, January, 2019

https://nordics.info/show/artikel/neutrality (09.03.2022)

https://ecfr.eu/wp-content/uploads/Ambiguous-alliance-Neutrality-opt-outs-and-European-defence.pdf (09.03.2022)

KAONGA, Gerrard: Russia Issues Ominous Warning to Finland, Sweden Should They Join NATO In: Newsweek, February, 2022

https://www.newsweek.com/russia-threatens-finland-sweden-nato-ukraine-invasion-1682715 (09.03.2022)

Lista: Så står partierna i Nato-frågan In: SVT Nyheter, December, 2020

https://www.svt.se/nyheter/inrikes/lista-sa-har-star-partierna-i-nato-fragan (09.03.2022)

Karl XIV Johan, King of Sweden and Norway (Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte) In: British Museum

https://www.britannica.com/place/Sweden/Bernadotte (09.03.2022)

MALMQVIST, Ambassador: Sweden and NATO – 23 years down the road In: NATO Review, January, 2018

https://www.nato.int/docu/review/articles/2018/01/11/sweden-and-nato-23-years-down-the-road/index.html#:~:text=In%202009%2C%20the%20Swedish%20parliament,in%20cooperation%20with%20other%20countries (09.03.2022)

Mutual Defence Clause (Article 42.7 TEU) In: European Parliament

https://www.europarl.europa.eu/meetdocs/2009_2014/documents/sede/dv/sede200612mutualdefsolidarityclauses_/sede200612mutualdefsolidarityclauses_en.pdf (09.03.2022)

Partnership for Peace programme In: NATO

https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_50349.htm (09.03.2022)

PÉTER Bajtay: A svéd semlegesség és történelmi gyökerei In: Információs Szemle 1989/3

Russian jets practised attacks on Sweden In: The Local, April, 2013

https://www.thelocal.se/20130422/47474/ (09.03.2022)

SCOTT, Franklin Daniel: On the Road to Neutrality and Peace In: Sweden, the Nation’s History, 1988 p. 326 https://books.google.hu/books?id=Qv8zxie3A18C&pg=PA326&lpg=PA326&dq=%22to+go+their+way+in+quiet+and+calm%22&source=bl&ots=dT_sQmXJEi&sig=ACfU3U24lj0BK627B2eD96ojSnfUslRoBw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjxudyh8KH2AhWHraQKHR65AdgQ6AF6BAgCEAM#v=onepage&q=%22to%20go%20their%20way%20in%20quiet%20and%20calm%22&f=false (09.03.2022)

SHAIKH, Zaki; ROSENBAUM, Andrew Jay: Russia has long history of airspace violations In: Anadolu Agency, October, 2015

https://www.aa.com.tr/en/politics/russia-has-long-history-of-airspace-violations/436331 (09.03.2022)

SOLYMOSSY, Péter: A semleges Svédország In: Magyar Revízió Svéd Szemmel, 2000

http://www.gecse.eu/s2.htm (09.03.2022)

SOPHIE, Clara; FRANKE, Ulrike: Ambiguous alliance: Neutrality, opt-outs, and European defence In: European Council on Foreign Relations, June, 2021

https://ecfr.eu/wp-content/uploads/Ambiguous-alliance-Neutrality-opt-outs-and-European-defence.pdf (09.03.2022)

STANDISH, Rein: Fearing Russian Bear, Sweden Inches Toward NATO In: Foreign policy, May, 2016

https://foreignpolicy.com/2016/05/25/fearing-russian-bear-sweden-inches-toward-nato-finland-moscow-military/ (09.03.2022)

Svédország geopolitikai helyzetképe a XXI. században In: PAGEO Geopolitikai Kutatóintézet, Oct. 2016

http://www.geopolitika.hu/hu/2016/10/04/svedorszag-geopolitikai-helyzetkepe-a-xxi-szazadban/ (09.03.2022)

Sweden in the EU In: Facts About the EU, August, 2021

https://eu.riksdagen.se/siteassets/8.-global/ladda-ner-och-bestall/pdf/sweden-in-the-eu (09.03.2022)

Sweden suspects Russian submarine got stranded in its waters In: Euractiv, October, 2014

https://www.euractiv.com/section/global-europe/news/sweden-suspects-russian-submarine-got-stranded-in-its-waters/ (09.03.2022)

Swedish defence minister calls Russian violation of airspace 'unacceptable' In: Reuters, March, 2022

https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/swedish-armed-forces-says-russian-fighter-jets-violated-swedish-airspace-2022-03-02/ (09.03.2022)

SWISHER, Kara: Sweden’s ‘Crazy’ 500% Interest Rate In: The Washington Post, September, 1992

https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1992/09/18/swedens-crazy-500-interest-rate/c3750e89-8fa8-44f4-9028-49f3c0d6c61c/ (09.03.2022)

What price neutrality? In: The Economist, June, 2014

https://www.economist.com/europe/2014/06/21/what-price-neutrality (09.03.2022)

Endnotes

[1] SOLYMOSSY, Péter: A semleges Svédország In: Magyar Revízió Svéd Szemmel, 2000

http://www.gecse.eu/s2.htm (09.03.2022)

[2] Karl XIV Johan, King of Sweden and Norway (Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte) In: British Museum

https://www.britannica.com/place/Sweden/Bernadotte (09.03.2022)

[3] SCOTT, Franklin Daniel: On the Road to Neutrality and Peace In: Sweden, the Nation’s History, 1988 p. 326 https://books.google.hu/books?id=Qv8zxie3A18C&pg=PA326&lpg=PA326&dq=%22to+go+their+way+in+quiet+and+calm%22&source=bl&ots=dT_sQmXJEi&sig=ACfU3U24lj0BK627B2eD96ojSnfUslRoBw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjxudyh8KH2AhWHraQKHR65AdgQ6AF6BAgCEAM#v=onepage&q=%22to%20go%20their%20way%20in%20quiet%20and%20calm%22&f=false (09.03.2022)

[4] Svédország geopolitikai helyzetképe a XXI. században In: PAGEO Geopolitikai Kutatóintézet, Oct. 2016

http://www.geopolitika.hu/hu/2016/10/04/svedorszag-geopolitikai-helyzetkepe-a-xxi-szazadban/ (09.03.2022)

[5] PÉTER Bajtay: A svéd semlegesség és történelmi gyökerei In: Információs Szemle 1989/3, pp. 101-111

[6] SOLYMOSSY, Péter: A semleges Svédország In: Magyar Revízió Svéd Szemmel, 2000

http://www.gecse.eu/s2.htm (09.03.2022)

[7] ÅSELIUS, Gunnar: Swedish Strategic Culture after 1945 In: JStor, 2005

https://www.jstor.org/stable/45084413 (09.03.2022)

[8] EAKIN, Hugh: The Swedish Kings of Cyberwar In: The New York Review, January, 2017

https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2017/01/19/the-swedish-kings-of-cyberwar/ (09.03.2022)

[9] ELIASSON, Johan: Traditions, Identity and Security: The Legacy of Neutrality in Finnish and Swedish Security Policies in Light of European Integration In: Research Gate, June, 2004

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/5014999_Traditions_Identity_and_Security_The_Legacy_of_Neutrality_in_Finnish_and_Swedish_Security_Policies_in_Light_of_European_Integration (09.03.2022)

[10] DALSJÖ, Robert: The hidden rationality of Sweden's policy of neutrality during the Cold War In:Taylor&Francis Online, Apr, 2013

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14682745.2013.765865 (09.03.2022)

[11] GÖTZ, Norbert: Neutrality and the Nordic countries In: Nordics Info, January, 2019

https://nordics.info/show/artikel/neutrality (09.03.2022)

[12] ELIASSON, Johan: Traditions, Identity and Security: The Legacy of Neutrality in Finnish and Swedish Security Policies in Light of European Integration In: Research Gate, June, 2004

http://aei.pitt.edu/7171/1/European_Integration_Papers_Online_Johan_Eliasson_manuscript.pdf (09.03.2022)

[13] SWISHER, Kara: Sweden’s ‘Crazy’ 500% Interest Rate In: The Washington Post, September, 1992

https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1992/09/18/swedens-crazy-500-interest-rate/c3750e89-8fa8-44f4-9028-49f3c0d6c61c/ (09.03.2022)

[14] Sweden in the EU In: Facts About the EU, August, 2021

https://eu.riksdagen.se/siteassets/8.-global/ladda-ner-och-bestall/pdf/sweden-in-the-eu (09.03.2022)

[15] Mutual Defence Clause (Article 42.7 TEU) In: European Parliament

https://www.europarl.europa.eu/meetdocs/2009_2014/documents/sede/dv/sede200612mutualdefsolidarityclauses_/sede200612mutualdefsolidarityclauses_en.pdf (09.03.2022)

[16] SOPHIE, Clara; FRANKE, Ulrike: Ambiguous alliance: Neutrality, opt-outs, and European defence In: European Council on Foreign Relations, June, 2021 p. 4

https://ecfr.eu/wp-content/uploads/Ambiguous-alliance-Neutrality-opt-outs-and-European-defence.pdf (09.03.2022)

[17] Ett användbart försvar - Regeringens proposition, 2008

https://www.regeringen.se/49bb67/contentassets/1236f9bd880b495f8a9dd94ce1cb71de/ett-anvandbart-forsvar-prop-200809140 (09.03.2022)

[18] MALMQVIST, Ambassador: Sweden and NATO – 23 years down the road In: NATO Review, January, 2018

https://www.nato.int/docu/review/articles/2018/01/11/sweden-and-nato-23-years-down-the-road/index.html#:~:text=In%202009%2C%20the%20Swedish%20parliament,in%20cooperation%20with%20other%20countries (09.03.2022)

[19] GäRTNER, Heinz: Engaged Neutrality: The Persistence of Neutrality in Post-Cold War Europe In: An Evolved Approach to the Cold War, 2002, p.89

https://books.google.hu/books?id=SsUpDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA89&lpg=PA89&dq=sweden+abandon+neutrality+%222002%22&source=bl&ots=oVZ1jFfnUw&sig=ACfU3U2eVpSxCe0KoGRtqMwWu6VdWsLScw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjEuNfWtKf2AhVIwQIHHRcJAsIQ6AF6BAgNEAM#v=onepage&q=sweden%20abandon%20neutrality%20%222002%22&f=false (09.03.2022)

[20] Current International Missions In: Swedish Armed Forces, February, 2020

https://www.forsvarsmakten.se/en/activities/current-international-missions/ (09.03.2022)

[21] SOPHIE, Clara; FRANKE, Ulrike: Ambiguous alliance: Neutrality, opt-outs, and European defence In: European Council on Foreign Relations, June, 2021 p. 35

https://ecfr.eu/wp-content/uploads/Ambiguous-alliance-Neutrality-opt-outs-and-European-defence.pdf (09.03.2022)

[22] Partnership for Peace programme In: NATO

https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_50349.htm (09.03.2022)

[23] What price neutrality? In: The Economist, June, 2014

https://www.economist.com/europe/2014/06/21/what-price-neutrality (09.03.2022)

[24] DUXBURY, Charles: Sweden Ratifies NATO Cooperation Agreement In: Atlantic Council, May, 2016

https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/natosource/sweden-ratifies-nato-cooperation-agreement/ (09.03.2022)

[25] Lista: Så står partierna i Nato-frågan In: SVT Nyheter, December, 2020

https://www.svt.se/nyheter/inrikes/lista-sa-har-star-partierna-i-nato-fragan (09.03.2022)

[26] Do you think Sweden should join the military alliance NATO? In: Statista, 2022

https://www.statista.com/statistics/660842/survey-on-perception-of-nato-membership-in-sweden/ (09.03.2022)

[27] STANDISH, Rein: Fearing Russian Bear, Sweden Inches Toward NATO In: Foreign policy, May, 2016

https://foreignpolicy.com/2016/05/25/fearing-russian-bear-sweden-inches-toward-nato-finland-moscow-military/ (09.03.2022)

[28] Sweden suspects Russian submarine got stranded in its waters In: Euractiv, October, 2014

https://www.euractiv.com/section/global-europe/news/sweden-suspects-russian-submarine-got-stranded-in-its-waters/ (09.03.2022)

[29] DUXBURY, Charlie: Sweden edges closer to NATO membership In: Politico, December, 2020

https://www.politico.eu/article/sweden-nato-membership-dilemma/ (09.03.2022)

[30] Russian jets practised attacks on Sweden In: The Local, April, 2013

https://www.thelocal.se/20130422/47474/ (09.03.2022)

[31] SHAIKH, Zaki; ROSENBAUM, Andrew Jay: Russia has long history of airspace violations In: Anadolu Agency, October, 2015

https://www.aa.com.tr/en/politics/russia-has-long-history-of-airspace-violations/436331 (09.03.2022)

[32] Swedish defence minister calls Russian violation of airspace 'unacceptable' In: Reuters, March, 2022

https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/swedish-armed-forces-says-russian-fighter-jets-violated-swedish-airspace-2022-03-02/ (09.03.2022)

[33] KAONGA, Gerrard: Russia Issues Ominous Warning to Finland, Sweden Should They Join NATO In: Newsweek, February, 2022

https://www.newsweek.com/russia-threatens-finland-sweden-nato-ukraine-invasion-1682715 (09.03.2022)