Kutatás / Geopolitika

29 Years of the Slovak Army

The actual beginnings of Slovak democracy can be traced back to 1998. The country’s economic development has since been speeding up, allowing an enhanced modernisation of the army. Since 2015, its military spending has been increasing significantly. In addition to the existing Black Hawk squadron, Slovakia will soon have an F-16 fleet. The question is what these capabilities are enough for if it comes to a real conflict.

The dissolution of Czechoslovakia

The birth of the autonomous Slovak Republic took effect on 1 January 1993 as an outcome of the dissolution of Czechoslovakia, or as it was officially called in its last days, the Czech and Slovak Federal Republic. The split did not primarily betide because of the will of its population but as an outcome of a deal made by the freshly elected premiers, Václav Klaus on the Czech and Vladimir Mečiar on the Slovak side. For fear of rejection, no public referendum was held on the separation.

Figure 1: Former Czechoslovakia in 1985. Source: Mapsland.com[1]

The disintegration of the federal state was carried out smoothly, in a peaceful way. Experiencing the Yugoslav civil war already underway at the time, this was not a negligible fact. Although there were fears in Slovakia that Hungary would make territorial claims against it, this assumption proved unfounded. Two new states were born in the middle of Europe, which formulated the same goals: to join the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation and the European Union. However, it was especially in these two spheres, in the military and the economic fields, where both Prague and Bratislava had to reorganise their structures completely.

Status of the military before the breakup

During the establishment and management of the Czechoslovak People's Army, it was a priority not to give a chance to form an independent Czech or Slovak military. Had this been the case, they would probably have conflicted with each other sooner or later. To provide the basis for Czechoslovakization, the displacement of the military personnel was a standard procedure. Residents of Slovakia, mainly Slovaks and ethnic Hungarians, completing their compulsory military service were usually sent to the Western parts of the country. In contrast, Czechs and ethnic Moravians had to apply for service generally in the Eastern and Southern regions, which the Slovaks and the Hungarians inhabited. This procedure helped blending the young generations and resulted in many ethnically mixed marriages.

The Czechoslovak Socialist Republic had an internationally recognised armaments industry specialising in tanks, aircraft, and explosives. However, these manufacturing fields were widely demolished after the Velvet Revolution, primarily to improve the country’s international image. This naive idea caused confusion and economic hardship, while rivals quickly filled the market spaces. A significant part of the military industry was located in Slovakia. The aim of this placement was twofold: on the one hand, the economically weaker regions needed constant investments; on the other hand, it was a strategic goal to put the armaments plants further away from the potential Western enemy. As a result of this, the downsizing of the arms industry hit primarily this region, which significantly increased the dissatisfaction of Slovaks with the central government located in Prague.[2]

The publication Czechoslovakia: A Country Study,[3] available on the Official Website of the US Marine Corps,[4] provides highly detailed data on the composition of the armaments of the Czechoslovak People's Army in the year 1987. According to the document, the number of active military personnel was around 201,000, of which approximately 100,000 were conscripts.[5] On a macro level, the army structure was divided into three main categories: arms (infantry, armour, artillery, engineers), auxiliary arms (signal, chemical, transportation) and services (medical, veterinarian, ordnance, quartermaster, administration, justice, topographic service).[6] At that time, the Czechoslovaks possessed around 3,000 T-54 and T-55 and 500 T-72 tanks. The number of artilleries was around 1,000 pieces. There were nuclear-capable rocket launchers in the inventory as well.

The Czechoslovak Air Force’s primary mission was to guarantee the safety of the country’s airspace and to provide air support for the ground forces in case of a conflict. According to the above-mentioned source, in 1987, the air force crew was around 56,000, two-thirds of which were career personnel. They possessed 465 combat aircraft (mainly MiG-21, MiG-23, Su-22, Aero L-19, and An-24) and approximately 40 armed helicopters. In 1987, 22 military and 14 reserve military airfields were operated in Czechoslovakia. Six of the latter were used in civil aviation.

Figure 2: Military and Reserve Military Airfields in 1987. Source: Czechoslovakia: A Country Study[7]

Building a new military

It is clear from the previous figures that the federal republic maintained a relatively strong army with a large number of personnel, especially in comparison with the recent trends. At the time when the country split, an agreement was made between the parties to distribute military assets among the successor states in a two-to-one ratio favouring the Czech Republic.[8] Immovable infrastructure was obviously inherited by the country on whose territory it was located. This caused some temporary confusion both in Prague and Bratislava since some facilities were only available in only one of the successor states.

In 1994 the Slovak National Council adopted the Defence Doctrine of the Slovak Republic, which proclaims that the country neither considers any state of being its enemy nor does it feel threatened by any of them. The document also opted for NATO membership and joined the Partnership for Peace programme.[9] Slovakia was not alone on this road, as in that year, 22 other states made the same move.[10] Most of them had a common goal: to gain experience, implement the army’s transformation, reach a higher level of interoperability and achieve NATO membership.

Barriers to the Western integration

Early Slovakia's democratic commitment was only present on the level of words, but not in its actions. Mečiar lost office in the Spring of 1994, but he was again the country’s prime minister by the end of the same year. His new coalition partners were both extremes: the far-right Slovak National Party and the far-left Association of Workers of Slovakia.[11] The government generated a continuous source of tension both domestically and internationally. Action against national and ethnic minorities became systemic. Organised crime groups gradually intertwined with the Slovak Information Service (SIS), and the police could not do their job as they regularly encountered political resistance. Mečiar’s relationship deteriorated with the head of the state, his former ally Michal Kováč and he did all he could to remove him. The PM did not shy away even from abducting the president's son by the secret service and smuggling him into Austria. The purpose of the operation was to discredit Kováč and force him to resign. The SIS was also behind the blast that claimed four lives and wounded twenty in Aranykéz street in Budapest. The perpetrators entered and left Hungary with Slovak diplomatic passports.[12] After the elections in 1998, the opposition’s extensive and wide cooperation managed to get rid of Mečiar.

A year after his fall, in 1999, the newly appointed head of intelligence presented a report[13] on SIS activities at a closed session of the National Council of the Slovak Republic. According to his words, SIS executed special intelligence operations beyond the borders of Slovakia, which, according to their official focus, were to influence the political situation in the neighbouring countries. In the frame of Operation “Omega” measures were taken to create the impression that from the USA's point of view, in the Central-European region Hungary is a privileged country at the expense of others. The “Most” (Eng. bridge) action aimed to provoke Austria's distrust of the Federal Republic of Germany. Operation “Neutron” aimed to generate controversy among the citizens of the Czech Republic about the country's accession to NATO. As part of Operation “Dežo”, active measures were taken to heat racist sentiments and sharpen the Roma issue among the citizens of the Czech Republic to prevent the country's admission into Euro-Atlantic structures. Operation “East” was supposed to convince the citizens of Slovakia about the country's alternative and rapid return to Russia's sphere of influence with an optimistic depiction of the perspective of more permanent ties between the two states. Democratic deficiency, hostile rhetoric and the above-mentioned operations severely damaged Slovakia's international reputation and contributed to the country's failure to be invited to join NATO in 1997.

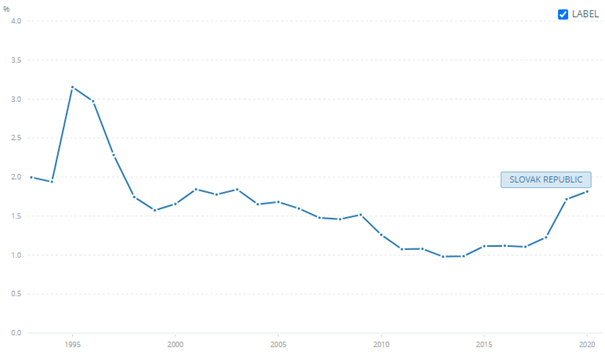

Figure 3: Military expenditure (% of GDP) Slovak Republic. Source: The World Bank[14]

Joining for a second run

Although Mečiar’s government almost every year fulfilled NATO’s financial expectations and spent 2% or even more of the GDP on the military, Slovakia unsurprisingly was not invited to join the organisation. During the South Slavic War, this was not an easy decision for the alliance from a military point of view. Hungary, which served as one of the fundamental bases for operations in Yugoslavia, had to enter NATO as an island. Slovakia’s growing international isolation, poor public safety, economic stagnation, and widespread cooperation among the various political oppositions were all needed to overthrow Mečiar in 1998.

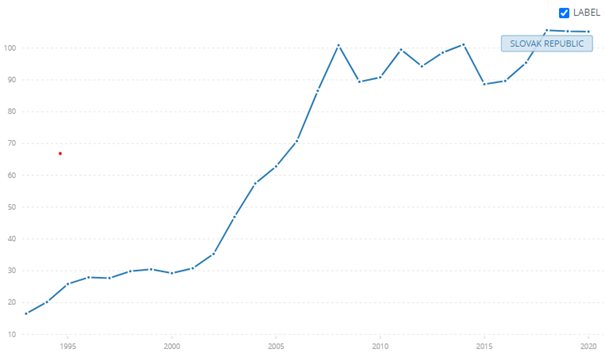

The real regime change in Slovakia took place that year. A broad coalition was formed, led by Mikuláš Dzurinda, which aimed to re-govern the country towards the Euro-Atlantic route. It was gratifying that the Hungarian Coalition Party also became a member of the new, western-oriented government. This move alleviated ethnic tensions dramatically. The result of the new leadership did not lag behind for long: in 2004, Slovakia became a member of both NATO and the European Union.

Figure 4: GDP (current USD) Slovak Republic. Source: The World Bank[15]

International missions before NATO accession

Participation in foreign missions was a priority for the newly founded Slovak Army. Although the provision of international military presence is always a sensitive and expensive issue, it also has many benefits for a country, especially in the case of a young one. These include the following: the opportunity to gain battlefield experience and try borderline situations, to test new technical assets, to motivate the personnel both professionally and financially, to improve morale and team spirit, and to increase the country's international prestige and reputation.

Between 1993 and 2004, the Armed Forces of the Slovak Republic participated in a total of 30 missions in 23 crisis areas, of which 15 were UN-led, 5 NATO-led, 2 EU-led, 3 OSCE-led and 5 coalition-led operations.[16]

Under the auspices of Partnership for Peace, Slovakia participated in several international missions. Between 1993-1999, the Army of the Slovak Republic was represented by 36 people in the UN Observer Missions in Angola (UNAVEM I[17], II[18], III[19] and MONUA[20]).[21] Between 1993-1998, the Engineer Battalion of the Slovak Army (with 606 troops and more than 400 pieces of equipment) was present in the UNPROFOR[22] and UNTAES[23] missions and fulfilled 894 professional tasks. The missions took place on the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Croatia. Their tasks included road repair and maintenance, mine clearance, bridge construction, renovation and rebuilding of local infrastructure.[24] Slovakia also participated in the UNOMIL[25] (Liberia, 1993-1994, 10 soldiers), UNOMUR[26] (Uganda and Rwanda, 1993-1994, 10 soldiers), UNAMIR[27] (Rwanda, 1993-1996), SFOR[28] (Bosnia and Herzegovina, 1999-2003), OSCE Mission to Moldova[29] (1998-2002), OSCE Kosovo Verification Mission[30] (1999-2000, 6 soldiers), OSCE Verification Mission in Albania (1999, Engineer Unit of the Slovak Army, 40 members), NATO KFOR (1999-2002), UNMEE[31] (Ethiopia and Eritrea, 2001-2004 Engineer Unit, 200 soldiers), UNMISET[32] (East Timor, 2001-2003, a military field hospital was sent). The Slovak Republic also participated in the Enduring Kuwait Mission in 2003. 74 members of the army operated for four months at Camp Doha within the 1st Czech and Slovak Radiation, Chemical and Biological Protection Battalion.[33] The helicopter unit of the military participated in the NATO-led SFOR[34] peace support operation in Bosnia and Herzegovina (2002-2003). One member of the army took part in the European Union-led military Operation Concordia[35] in the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (2003). The aim of the UNAMSIL[36] (1999-2005) mission in Sierra Leone was to monitor the security situation and demilitarisation process and observe the condition of human rights in the country. The Slovak Armed Forces participated in Operation Enduring Freedom[37] in Afghanistan (2005-2005). The main task of the 40-member unit, which consisted mainly of engineers and experts in maintenance and restoration, was to rebuild the airport near Bagram.[38] The Engineer Unit of the Armed Forces of the Slovak Republic participated in Operation Iraqi Freedom (2003-2007). They operated within the Polish sector between Bagdad and Basra. The main tasks were mine clearance, pyrotechnic works and weapons, and ammunition disposal.[39] As a fresh member of the European Union, Slovakia assigned two soldiers to an observer team in support of the African Union in Sudan/Darfur.[40]

The country’s most significant military loss is also linked to a foreign mission. On 19 January 2006, the 37-year-old Antonov AN-24V aeroplane, which transported the Slovak KFOR contingent home, which had ended its six-month mission in Kosovo, hit a hill and crashed in Hungarian airspace, just a few kilometres from its destination Košice. Of the 43 people on board, only one survived the accident.[41]

As a NATO member

Slovakia became a member of NATO in 2004. Despite its commitments, no compelling military asset acquisitions were made until 2015. That year, however, the Slovak government decided on significant military developments. First, a decision was made to purchase nine Sikorsky UH-60M Black Hawk helicopters, which are already in service.[42] In December 2018 an even larger volume of investment was approved. The political leadership decided to buy 14 F-16V fighter jets with a Block 70/72 configuration at a total cost of EUR 1.6 billion. The first aircraft will arrive this year, and all units are scheduled to be delivered by 2023. This move could make Slovakia, which currently has only 12 MiG-29 fighter jets (most of them are inoperable), one of the most potent air forces in the Central-European region.[43] In terms of onshore capabilities, Slovakia has only 22 T-72 tanks with uncertain performance.[44] New armoured equipment can be purchased after 2025 at the earliest.[45] In terms of numbers, the Slovak Armed Forces have declined significantly compared to Czechoslovak times. Until 31 December 2022, the Ministry of Defence of the Slovak Republic proposes to increase the numbers in the Armed Forces by 523 professional soldiers, 202 employees and 460 reserve soldiers. In total, they wish to have 23,983 employees in the Armed Forces of the Slovak Republic, of which 19,573 are soldiers.[46]

Since the outbreak of the Russian-Ukrainian war, Slovakia has been providing military aid for its neighbour. As part of this, the country handed over its only air defence device, the S-300 missile system, which Russian forces have, according to some sources[47], already destroyed. Slovakia denies this news. In addition, Slovakia provided millions of euros worth of military assets. The country has confronted the Russian Federation on an unprecedented scale, which is likely to cast a shadow on their bilateral relations in the future. However, it can also be said that the Slovak-Ukrainian relationship has never been as good as it is today.

Conclusion

Although for a long time Slovakia seemed to be the country of missed opportunities, the democratic transition is now successfully completed. Despite the fact that financial resources provided for the development of the Slovak Armed Forces initially even exceeded NATO expectations, the country, for political reasons and because of a democracy deficit could only join NATO in 2004. The development of the military is significant from 2015 onward. Today, a modern Black Hawk squadron is the backbone of the Slovak Air Forces. New F-16 jets are expected to arrive later this year, which is also outstanding on the regional level. However, Slovakia's air defence is weak at the moment. The only air defence system, the Russian-made S-300, was donated to Ukraine. Currently, the air protection of the critical infrastructure is performed by a Dutch and German Patriot battery.[48]

Bibliography

DENNIK N: Vláda rozhodla o nákupe za 1,6 miliardy. Armáde kúpi americké stíhačky F-16, ktoré presadila SNS. <11.07.2018> Access: https://e.dennikn.sk/1176979/vlada-rozhodla-o-historickom-nakupe-armade-kupi-americke-stihacky-f-16-ktore-presadila-sns/ (26.05.2022)

European External Action Service: Concordia. Access: https://eeas.europa.eu/archives/csdp/missions-and-operations/concordia/index_en.htm (25.05.2022)

FELVIDEK.MA: Eperjesen leszállt a három utolsó Black Hawk. <12.01.2020> Access: https://felvidek.ma/2020/01/eperjesen-leszallt-a-harom-utolso-black-hawk/ (26.05.2022)

GAWDIAK, Ihor: Czechoslovakia: A Country Study. Headquarters, Department of Army, 198p. pp. 235-238 Access: https://www.marines.mil/portals/1/Publications/Czechoslovakia%20Study_4.pdf?ver=2012-10-11-163237-750. (16.05.2022)

HN: Zničili sme systémy S-300, chváli sa Rusko. Tie naše to nie sú, reaguje Slovensko. <11.04.2022> Access: https://hnonline.sk/slovensko/25883582-znicili-sme-systemy-s-300-chvali-sa-rusko-tie-nase-to-nie-su-hovoria-slovaci (26.05.2022)

INDEX.HU: Amikor a Fogász vérbe borította a belvárost. <02.07.2018> Access: https://index.hu/belfold/2018/07/02/aranykez_utca_husz_ev/ (19.05.2022)

MAPSLAND.COM: Detailed political map of the former Czechoslovakia in 1985. Access: https://www.mapsland.com/maps/europe/czech-republic/large-detailed-political-and-administrative-map-of-czechoslovakia-with-roads-and-major-cities-1985.jpg (06.05.2022)

Marines Official. Access: https://www.marines.mil/ (15.05.2022)

Ministry of Defence of the Slovak Republic: EU supporting action to African Union in Sudan/Darfur. Access: https://www.mosr.sk/history-of-military-operations-abroad/#UNPROFOR (25.05.2022)

Ministry of Defence of the Slovak Republic: History of military operations abroad. Access: https://www.mosr.sk/history-of-military-operations-abroad/ (22.05.2022)

Ministry of Defence of the Slovak Republic: Mission Enduring Freedom, Kuwait (2003). Access: https://www.mosr.sk/history-of-military-operations-abroad/#UNPROFOR (24.05.2022)

Ministry of Defence of the Slovak Republic: Operation Enduring Freedom, Afghanistan (2002-2005). Access: https://www.mosr.sk/history-of-military-operations-abroad/#UNPROFOR (24.05.2022)

Ministry of Defence of the Slovak Republic: Operation Iraqi Freedom, Iraq (2003-2007). Access: https://www.mosr.sk/history-of-military-operations-abroad/#UNPROFOR (24.05.2022)

Ministry of Defence of the Slovak Republic: UNPROFOR – The United Nations Protection Force in the former Yugoslavia (1992-1995); UNTAES in Croatia – The United Nations Transitional Authority in Eastern Slavonia, Baranja and Western. Access: https://www.mosr.sk/history-of-military-operations-abroad/#UNPROFOR (24.05.2022)

Ministry of Innovation and Technology of Hungary – Traffic Safety Organisation: Aircraft Collided with a Hill While Approaching Košice Airport. Access: http://www.kbsz.hu/j25/en/aviation/occurrences-investigated/25-legi-kozlekedes/latest-sp-842/68-publikaciok-sp-712650579 (24.05.2022)

NATO Official: SFOR Fact Sheet. Access: https://www.nato.int/sfor/factsheet/factsheet.htm (24.05.2022)

NATO Official: SFOR – Stabilisation Force. Access: https://www.nato.int/sfor/ (25.05.2022)

NATO Official: The Partnership for Peace Programme. Access: https://www.sto.nato.int/Pages/partnership-for-peace.aspx (18.05.2022)

OSCE Official: OSCE Mission to Moldova. Access: https://www.osce.org/mission-to-moldova (25.05.2022)

OSCE Official: OSCE Kosovo Verification Mission/OSCE Task Force for Kosovo (closed). Access: https://www.osce.org/kvm-closed (25.05.2022)

PEACEKEEPING.UN.ORG: Angola – UNAVEM I Background. Access: https://peacekeeping.un.org/sites/default/files/past/unavem1/UnavemIB.htm (20.05.2022)

PEACEKEEPING.UN.ORG: Angola – UNAVEM II Background. Access: https://peacekeeping.un.org/sites/default/files/past/Unavem2/UnavemIIB.htm (20.05.2022)

PEACEKEEPING.UN.ORG: Angola – MONUA Facts and figures. Access: https://peacekeeping.un.org/sites/default/files/past/monua/monuaf.htm (21.05.2022)

PEACEKEEPING.UN.ORG: Angola United Nations Angola Verification Mission III – UNAVEM III. Access: https://peacekeeping.un.org/sites/default/files/past/unavem3.htm (21.05.2022)

PEACEKEEPING.UN.ORG: Croatia United Nations Transitional Authority in Eastern Slavonia, Baranja and Western – UNTAES. Access: https://peacekeeping.un.org/sites/default/files/past/untaes.htm (23.05.2022)

PEACEKEEPING.UN.ORG: Liberia United Nations Observer Mission in Liberia – UNOMIL. Access: https://peacekeeping.un.org/sites/default/files/past/unomil.htm (24.05.2022)

PEACEKEEPING.UN.ORG: Rwanda United Nations Assistance Mission in Rwanda – UNAMIR. Access: https://peacekeeping.un.org/sites/default/files/past/unamir.htm (25.05.2022)

PEACEKEEPING.UN.ORG: Uganda – Rwanda – UNOMUR. Access: https://peacekeeping.un.org/sites/default/files/past/unomurbackgr.html (24.05.2022)

PEACEKEEPING.UN.ORG: UNMISET United Nations Mission of Support in East Timor. Access: https://peacekeeping.un.org/mission/past/unmiset/index.html (26.05.2022)

PEACEKEEPING.UN.ORG: UNAMSIL United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone. Access: https://peacekeeping.un.org/mission/past/unamsil/ (25.05.2022)

PEACEKEEPING.UN.ORG: UNPROFOR Fact Sheet. Access: https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/mission/unprofor (23.05.2022)

REICHARDT, David: Democracy Promotion in Slovakia an Import or an Export Business? (The influence of international relations on civil society in a transitional state). In.

Perspectives, No. 18. <2002> pp. 5-20. Access: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23615824?read-now=1&refreqid=excelsior%3A1c726f6e2d053e4b5658f1284eaad598&seq=2 (19.05.2022)

Senate Hearing – Committee on Armed Services United States Senate: Operation Enduring Freedom. Access: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-107shrg83471/html/CHRG-107shrg83471.htm (19.05.2022)

SME: Dvadsať tankov a dvanásť lietadiel? Ako vyzerá slovenská armáda. <21.06.2017> Access: https://domov.sme.sk/c/20564436/co-ostalo-z-armady-a-kolko-do-nej-stat-nalieva-penazi.html (26.05.2022)

SME.SK: Správa V. Mitra o plnení úloh SIS. <18.02.1999> Access: https://www.sme.sk/c/2179771/sprava-v-mitra-o-plneni-uloh-sis.html (19.05.2022)

SZAYNA, Thomas S.: The Military in a Postcommunist Czechslovakia. In. RAND. <1992> pp. 55-58. Access: https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/notes/2009/N3412.pdf (16.05.2022)

THE WORLD BANK Official: GDP (current US$) – Slovak Republic. Access: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?end=2020&locations=SK&start=1993 (20.05.2022)

THE WORLD BANK Official: Military expenditure (% of GDP) – Slovak Republic. Access: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.XPND.GD.ZS?end=2020&locations=SK&start=1993&view=chart (20.05.2022)

TREND.SK: Holandsko a Nemecko pošlú na Slovensko tri systémy Patriot. <18.03.2022> Access: https://www.trend.sk/spravy/holandsko-nemecko-poslu-slovensko-tri-systemy-patriot (26.05.2022)

TREND.SK: Slovenská armáda do konca roku 2022 navýši svoje stavy. Vojakov bude takmer 20-tisíc. <20.08.2021> Access: https://www.trend.sk/spravy/slovenska-armada-konca-roku-2022-navysi-svoje-stavy-vojakov-bude-takmer-20-tisic (26.05.2022)

UNMEE.UNMISSIONS.ORG: United Nations Mission in Ethiopia. Access: https://unmee.unmissions.org/ (26.05.2022)

VIDA, Csaba: A szlovák haderő külföldi katonai szerepvállalása (1993-2004). In. Felderítő Szemle. Budapest 2005. p.47. Access: http://www.knbsz.gov.hu/hu/letoltes/fsz/2005-1.pdf (20.05.2022)

WATERS, Trevor: Budovanie armády z ničoho: namáhavý zápas Slovenska. In. Medzinárodné otázky, Vol. 7, No. 4. <1998> p. 63. Access: https://www.jstor.org/stable/44961031?read-now=1&refreqid=excelsior%3A5f83a5a51a8a580d8b248d22290c85db&seq=5 (17.05.2022)

WATERS, Trevor: Building an Army from Scratch: Slovakia’s uphill Struggle. In. Medzinárodné otázky. Vol. 7, No. 4 (1998), p.51 Access: https://www.jstor.org/stable/44961031?read-now=1&refreqid=excelsior%3A5f83a5a51a8a580d8b248d22290c85db&seq=5 (17.05.2022)

Webnoviny.sk: Ministerstvo obrany ide modernizovať staré tanky a po roku 2025 nakúpi nové. <07.01.2019> Access: https://www.webnoviny.sk/ministerstvo-obrany-ide-modernizovat-stare-tanky-a-po-roku-2025-nakupi-nove/ (26.05.2022)

Endnotes

[1] A full range of details on armaments is available to those interested in the publication: GAWDIAK, Ihor: Czechslovakia – a country study. In. Federal Research Division Library of Congress. <1987> Access: https://www.marines.mil/portals/1/Publications/Czechoslovakia%20Study_1.pdf?ver=2012-10-11-163237-750 (05/16/2022)

[1] MAPSLAND.COM: Detailed political map of the former Czechoslovakia in 1985. Access: https://www.mapsland.com/maps/europe/czech-republic/large-detailed-political-and-administrative-map-of-czechoslovakia-with-roads-and-major-cities-1985.jpg (06.05.2022)

[2] SZAYNA, Thomas S.: The Military in a Postcommunist Czechslovakia. In. RAND. <1992> pp. 55-58. Access: https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/notes/2009/N3412.pdf (16.05.2022)

[3] GAWDIAK, Ihor: Czechslovakia – a country study. In. Federal Research Division Library of Congress. <1987> Access: https://www.marines.mil/portals/1/Publications/Czechoslovakia%20Study_1.pdf?ver=2012-10-11-163237-750 (16.05.2022)

[4] Marines Official. Access: https://www.marines.mil/ (15.05.2022)

[5] Czechoslovakia: A Country Study; Manpower, barbed wire, and electronics – important elements of national security in Czechoslovakia. pp. 235-238 Access: https://www.marines.mil/portals/1/Publications/Czechoslovakia%20Study_4.pdf?ver=2012-10-11-163237-750. (16.05.2022)

[6] Ibid. pp. 235-238

[7] Ibid. p.240

[8] WATERS, Trevor: Budovanie armády z ničoho: namáhavý zápas Slovenska. In. Medzinárodné otázky, Vol. 7, No. 4. <1998> p. 63. Access: https://www.jstor.org/stable/44961031?read-now=1&refreqid=excelsior%3A5f83a5a51a8a580d8b248d22290c85db&seq=5 (17.05.2022)

[9] WATERS, Trevor: Building an Army from Scratch: Slovakia’s uphill Struggle. In. Medzinárodné otázky

Vol. 7, No. 4 (1998), p.51 Access: https://www.jstor.org/stable/44961031?read-now=1&refreqid=excelsior%3A5f83a5a51a8a580d8b248d22290c85db&seq=5 (17.05.2022)

[10] NATO Official: The Partnership for Peace Programme. Access: https://www.sto.nato.int/Pages/partnership-for-peace.aspx (18.05.2022)

[11] REICHARDT, David: Democracy Promotion in Slovakia an Import or an Export Business? (The influence of international relations on civil society in a transitional state). In.

Perspectives, No. 18. <2002> pp. 5-20. Access: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23615824?read-now=1&refreqid=excelsior%3A1c726f6e2d053e4b5658f1284eaad598&seq=2 (19.05.2022)

[12] INDEX.HU: Amikor a Fogász vérbe borította a belvárost. <02.07.2018> Access: https://index.hu/belfold/2018/07/02/aranykez_utca_husz_ev/ (19.05.2022)

[13] SME.SK: Správa V. Mitra o plnení úloh SIS. <18.02.1999> Access: https://www.sme.sk/c/2179771/sprava-v-mitra-o-plneni-uloh-sis.html (19.05.2022)

[14] THE WORLD BANK Official: Military expenditure (% of GDP) – Slovak Republic. Access: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.XPND.GD.ZS?end=2020&locations=SK&start=1993&view=chart (20.05.2022)

[15] THE WORLD BANK Official: GDP (current US$) – Slovak Republic. Access: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?end=2020&locations=SK&start=1993 (20.05.2022)

[16] VIDA, Csaba: A szlovák haderő külföldi katonai szerepvállalása (1993-2004). In. Felderítő Szemle. Budapest 2005. p.47. Access: http://www.knbsz.gov.hu/hu/letoltes/fsz/2005-1.pdf (20.05.2022)

[17] PEACEKEEPING.UN.ORG: Angola – UNAVEM I Background. Access: https://peacekeeping.un.org/sites/default/files/past/unavem1/UnavemIB.htm (20.05.2022)

[18] PEACEKEEPING.UN.ORG: Angola – UNAVEM II Background. Access: https://peacekeeping.un.org/sites/default/files/past/Unavem2/UnavemIIB.htm (20.05.2022)

[19] PEACEKEEPING.UN.ORG: Angola United Nations Angola Verification Mission III – UNAVEM III. Access: https://peacekeeping.un.org/sites/default/files/past/unavem3.htm (21.05.2022)

[20] PEACEKEEPING.UN.ORG: Angola – MONUA Facts and figures. Access: https://peacekeeping.un.org/sites/default/files/past/monua/monuaf.htm (21.05.2022)

[21] Ministry of Defence of the Slovak Republic: History of military operations abroad. Access: https://www.mosr.sk/history-of-military-operations-abroad/ (22.05.2022)

[22] PEACEKEEPING.UN.ORG: UNPROFOR Fact Sheet. Access: https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/mission/unprofor (23.05.2022)

[23] PEACEKEEPING.UN.ORG: Croatia United Nations Transitional Authority in Eastern Slavonia, Baranja and Western – UNTAES. Access: https://peacekeeping.un.org/sites/default/files/past/untaes.htm (23.05.2022)

[24] Ministry of Defence of the Slovak Republic: UNPROFOR – The United Nations Protection Force in the former Yugoslavia (1992-1995); UNTAES in Croatia – The United Nations Transitional Authority in Eastern Slavonia, Baranja and Western. Access: https://www.mosr.sk/history-of-military-operations-abroad/#UNPROFOR (24.05.2022)

[25] PEACEKEEPING.UN.ORG: Liberia United Nations Observer Mission in Liberia – UNOMIL. Access: https://peacekeeping.un.org/sites/default/files/past/unomil.htm (24.05.2022)

[26] PEACEKEEPING.UN.ORG: Uganda – Rwanda – UNOMUR. Access: https://peacekeeping.un.org/sites/default/files/past/unomurbackgr.html (24.05.2022)

[27] PEACEKEEPING.UN.ORG: Rwanda United Nations Assistance Mission in Rwanda – UNAMIR. Access: https://peacekeeping.un.org/sites/default/files/past/unamir.htm (25.05.2022)

[28] NATO Official: SFOR – Stabilisation Force. Access: https://www.nato.int/sfor/ (25.05.2022)

[29] OSCE Official: OSCE Mission to Moldova. Access: https://www.osce.org/mission-to-moldova (25.05.2022)

[30] OSCE Official: OSCE Kosovo Verification Mission/OSCE Task Force for Kosovo (closed). Access: https://www.osce.org/kvm-closed (25.05.2022)

[31] UNMEE.UNMISSIONS.ORG: United Nations Mission in Ethiopia. Access: https://unmee.unmissions.org/ (26.05.2022)

[32] PEACEKEEPING.UN.ORG: UNMISET United Nations Mission of Support in East Timor. Access: https://peacekeeping.un.org/mission/past/unmiset/index.html (26.05.2022)

[33] Ministry of Defence of the Slovak Republic: Mission Enduring Freedom, Kuwait (2003). Access: https://www.mosr.sk/history-of-military-operations-abroad/#UNPROFOR (24.05.2022)

[34] NATO Official: SFOR Fact Sheet. Access: https://www.nato.int/sfor/factsheet/factsheet.htm (26.05.2022)

[35] European External Action Service: Concordia. Access: https://eeas.europa.eu/archives/csdp/missions-and-operations/concordia/index_en.htm (25.05.2022)

[36] PEACEKEEPING.UN.ORG: UNAMSIL United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone. Access: https://peacekeeping.un.org/mission/past/unamsil/ (25.05.2022)

[37] Senate Hearing – Committee on Armed Services United States Senate: Operation Enduring Freedom. Access: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-107shrg83471/html/CHRG-107shrg83471.htm (19.05.2022)

[38] Ministry of Defence of the Slovak Republic: Operation Enduring Freedom, Afghanistan (2002-2005). Access: https://www.mosr.sk/history-of-military-operations-abroad/#UNPROFOR (24.05.2022)

[39] Ministry of Defence of the Slovak Republic: Operation Iraqi Freedom, Iraq (2003-2007). Access: https://www.mosr.sk/history-of-military-operations-abroad/#UNPROFOR (25.05.2022)

[40] Ministry of Defence of the Slovak Republic: EU supporting action to African Union in Sudan/Darfur. Access: https://www.mosr.sk/history-of-military-operations-abroad/#UNPROFOR (25.05.2022)

[41] Ministry of Innovation and Technology of Hungary – Traffic Safety Organisation: Aircraft Collided with a Hill While Approaching Košice Airport. Access: http://www.kbsz.hu/j25/en/aviation/occurrences-investigated/25-legi-kozlekedes/latest-sp-842/68-publikaciok-sp-712650579 (26.05.2022)

[42] FELVIDEK.MA: Eperjesen leszállt a három utolsó Black Hawk. <12.01.2020> Access: https://felvidek.ma/2020/01/eperjesen-leszallt-a-harom-utolso-black-hawk/ (26.05.2022)

[43] DENNIK N: Vláda rozhodla o nákupe za 1,6 miliardy. Armáde kúpi americké stíhačky F-16, ktoré presadila SNS. <11.07.2018> Access: https://e.dennikn.sk/1176979/vlada-rozhodla-o-historickom-nakupe-armade-kupi-americke-stihacky-f-16-ktore-presadila-sns/ (26.05.2022)

[44] SME: Dvadsať tankov a dvanásť lietadiel? Ako vyzerá slovenská armáda. <21.06.2017> Access: https://domov.sme.sk/c/20564436/co-ostalo-z-armady-a-kolko-do-nej-stat-nalieva-penazi.html (26.05.2022)

[45] Webnoviny.sk: Ministerstvo obrany ide modernizovať staré tanky a po roku 2025 nakúpi nové. <07.01.2019> Access: https://www.webnoviny.sk/ministerstvo-obrany-ide-modernizovat-stare-tanky-a-po-roku-2025-nakupi-nove/ (26.05.2022)

[46] TREND.SK: Slovenská armáda do konca roku 2022 navýši svoje stavy. Vojakov bude takmer 20-tisíc. <20.08.2021> Access: https://www.trend.sk/spravy/slovenska-armada-konca-roku-2022-navysi-svoje-stavy-vojakov-bude-takmer-20-tisic (26.05.2022)

[47] HN: Zničili sme systémy S-300, chváli sa Rusko. Tie naše to nie sú, reaguje Slovensko. <11.04.2022> Access: https://hnonline.sk/slovensko/25883582-znicili-sme-systemy-s-300-chvali-sa-rusko-tie-nase-to-nie-su-hovoria-slovaci (26.05.2022)

[48] TREND.SK: Holandsko a Nemecko pošlú na Slovensko tri systémy Patriot. <18.03.2022> Access: https://www.trend.sk/spravy/holandsko-nemecko-poslu-slovensko-tri-systemy-patriot (26.05.2022)