Kutatás / Geopolitika

Foreign and Economic Policy of the V4

The V4-EU-NATO foreign policy cooperation intertwines in increasing energy security and diversification in Europe and in promoting Transatlantic integration of the Eastern and West Balkan neighboring countries. The views of the V4 are much more divided on Russia and China-related foreign policy, however the Visegrad members have shared interests in the field of energy and economic cooperation with the East. The most significant challenge for the Visegrad Group economies is the digital and energy transition, which will be a new strategic area of V4 cooperation in the coming years

Keywords: Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia, V4, Visegrad group, foreign policy, economic policy, EU, US, China, Russia, green transition, Industry 4.0.

After 2004, the primary framework of foreign policy priorities and aspirations of the V4 Group centred on EU and NATO membership, and respecting the common values and ambitions of these alliances. Neighbourhood policy, support of the Western Balkan nations, and EaP countries toward European integration became a priority area in the Visegrad Group’s EU foreign policy.[i] The V4-US foreign policy ambitions complement EU objectives: specifically, contributions to the democratization process in the region and cooperation in energy security and diversification. The foreign policy of the Visegrad countries toward Russia and China is much less coherent, as national, regional, and allied interests often do not coincide. The enhanced economic cooperation of the V4 guarantees the Group’s sustainable competitiveness by supporting digital and energy transition.

The Visegrad Cooperation might be considered as a platform of non-institutionalized cooperation providing its four member countries with strengthened advocacy of their common foreign policy interests.

In the first half of the 30 years of the V4 the defining common foreign policy direction was the Euro-Atlantic integration (NATO and EU accession) followed by the deepening of an inter-allied cooperation (Schengen area membership). At the same time, NATO and EU memberships have determined the future of the V4’s foreign policy both at group and country-levels. As another consequence of the accession to NATO and the EU the foreign policy of the V4’s became multi-layered, as in addition to their traditional foreign policy aspirations the need for advocacy within integration has emerged.

V4-EU foreign policy

By achieving EU integration the V4 countries are no longer the recipients of EU policies - they contribute to shaping EU policies through their participation. Based on the national interests (including the issue of national minorities[ii]) and the geographic location of its member countries, the V4 was a committed supporter of deepening relationships with countries in its neighborhood[iii] even before its own EU accession. After 2004 support for rapprochement of the Western Balkans with the EU, also advocating the Eastern Partnership (Kroměříž declaration 2004[iv], Bratislava Declaration 2011[v]) simultaneously and consistently appeared among the V4s foreign policy goals.

The framework for the conciliation of the settled V4’s positions in the European Union is provided by the V4 presidency mechanism through which a given Visegrad country assumes the task of federal coordination[vi] on a rotating basis for one year, including defining foreign policy priorities of the Visegrad Group.[vii] After acquiring EU membership the V4’s foreign policy directions concerning the “active contribution to the development of the CFSP including the "Wider Europe - New Neighbourhood" policy and the EU strategy towards the Western Balkans” [viii] have been formulated as the main areas of desired future cooperation within and toward the EU. The main principle of the V4’s influence on this matter is based on their specific knowledge of the “transition know-how”, which enables them to ”capitalize their unique experiences”[ix] concerning democratic transformation and transition processes, moreover they can share their own experience regarding the EU accession process with the EU candidate countries.[x] On the level of joint declarations, this commitment has been present in the Visegrad Four foreign policy agenda since 2005 (Hungarian Presidency) appointing the areas of cooperation “in the processes of mediation of values, stabilization and in sharing experience.”[xi] Four years later, the Hungarian presidency provided a framework to the V4 foreign minister-level meeting dedicated to the Western Balkans emphasizing the positive impact of Croatia’s accession to the EU, also offering “twinning cooperation and joint V4 twinning projects to partners from the WB region.”[xii] The actual 2020/2021 foreign policy objectives (Polish Presidency) reiterate the support toward the pro-integration aspirations of the Western Balkan countries, also stipulating the importance of “exchanging V4's experience with the WB countries on the EU accession process (...) motivating them to carry out necessary reforms.” 13

V4+US

In the first third of its history the V4's foreign policy focused on NATO integration. After becoming full-fledged members of the Transatlantic Alliance (1999 and 2004) security and defense policy remained an area of long-term joint interest between the US and the Visegrad Group. Since the Group’s EU accession (2004) the most fruitful V4-US foreign policy cooperation areas were those which were in line with EU objectives and contributed to the democratization process in the region. Accordingly, the V4 and US goals have particularly strong complementarity in the context of enlargement policy into Euro-Atlantic Institutions. Agendas of the V4 group-level meetings with Washington in the frame of the V4+ format show continuity of shared interests over decades.[1] The integration process of the Western Balkans alongside the Polish-Swedish initiative EU Eastern Partnership is primarily where the V4 can effectively assert Washington’s support.[2] The diversification of the V4’s energy supplies (in coherence with the EU Energy Security Strategy)[xiii] also meets the US’s geopolitical and economic interests: reducing Russia’s influence in the region while strengthening its position on the European energy market.[xiv] The Trump administration gave positive feedback on the Three Seas Initiative[xv] emphasizing the “shared focus on expanding infrastructure enhancing business connections, strengthening energy security and reducing barriers to free, fair, and reciprocal trade.”[xvi] Under the Biden presidency, the strong US support for TSI continues as it contributes to the EU integration by building better infrastructure, and increases stability and well-being of the region by strengthening the energy security.[xvii]

On the occasion of the 30th anniversary of the V4, the official congratulations of the US set out the possible directions for future cooperation, which are “fighting and recovering from the global pandemic, improving cyber and energy security, combating climate change, countering disinformation and malign influence, and strengthening democratic institutions, the rule of law, and independent media”.[xviii]

Russia – point of difference

Foreign policy toward Russia is one of the areas where there is significant non-coherence between the V4 and the EU. Within the Visegrad Group, the Slovakia-Hungary axis pursues a pragmatic foreign policy toward Russia, which is often not in line with EU-Russia foreign policy relations either.

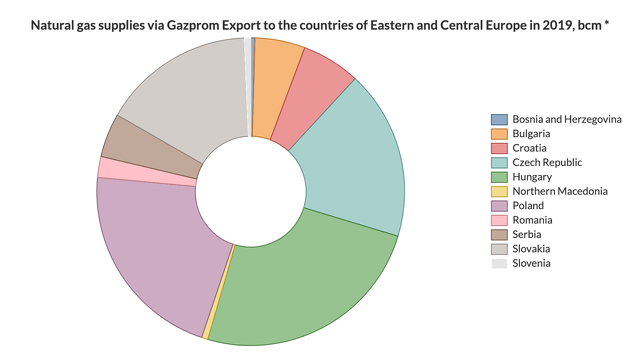

From a historical perspective, the establishment of Visegrad cooperation itself was intended to provide the framework to a political “restart” for the former Warsaw Pact member states facilitating their transition process toward the Euro-Atlantic integration. Despite the V4’s successful Western integration on a political and security cooperation level Russia preserved its unquestionable influence on the region through the energy sector. The Ukrainian gas crisis in 2009 highlighted the vulnerability of the region’s energy supply[xix] caused by its energy dependency on Russian companies and at the same time forced the V4 countries to improve the diversification of their energy delivery sources. The energy security and its reshaping are declared[xx] priority areas of the Visegrad Group cooperation,[xxi] however over the last decade the Visegrad Countries became even more dependent on overall energy import also they were the biggest Russian natural gas consumers in the Eastern and Central European[3] market in 2019.

Share of the Russian natural gas import in Eastern and Central Europe[xxii]

Different approaches of the V4 countries to the military crises with Russian involvement might serve as an indicator of divergent foreign policy positions within the Group. The V4 does not formulate a common position on Russia regarding the Russian-Georgian war in 2008[xxiii] also in the context of the 2014 conflict in Eastern Ukraine dividing lines within the Group emerge even more along with diverging interests and perspectives.[4] Disagreement on prioritization between the possible negative economic consequences of the EU sanctions against Russia and the threat of a growing security risk in Eastern Europe caused struggle on the V4-EU level[xxiv] and also within the Visegrad Group.[xxv] After all, the V4 leaders’ commitment towards the protection of one's economic interests did not lead to a formal veto against the EU sanctions, as the worsening security situation in their neighbourhood convinced them about the inevitability of maintaining such measures.[xxvi]

Poland, as the most committed supporter of the Transatlantic Partnership, pursues the most Russia-sceptical foreign policy despite the adverse consequences on its economy.[5] The foreign policy of the Czech Republic is close to Poland’s position often expressing its concerns over human rights issues in Russia.[xxvii] Within the V4 group, Hungary conducts the most pragmatical pro-Russia foreign policy announcing its “Eastern opening” strategy from 2010[xxviii] strengthening its energy ties with Russia,[xxix] and often referring to the Russian concept of democracy as an example to follow.[xxx] Slovakia represents the moderate part of the pro-Russian axis within the V4: its “permissive criticism” was demonstrated on a diplomatic level,[6] also in its advocacy for higher involvement of the Russian authorities in international organizations.[xxxi]

V4-China relations

...

[1] In 2010 the V4 top foreign policy officials visited to Washington, discussing wider opportunities for cooperation in the field of research (think-tanks, academics, policy analysts).

(https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/126819/021411_ACUS_Basora_VisegradFour.pdf p.2) The 2015 meeting of the V4 political directors in Washington was focused on issues as “stability in the European neighborhood, energy cooperation, and regional security”. (https://washington.mfa.gov.hu/eng/news/v4-political-directors-meeting-in-the-state-department) The 2017 Polish Presidency Program highlights the importance of the cooperation in frame of the V4+US format, considering the energy security and the transatlantic relations as priority cooperation areas. (https://www.visegradgroup.eu/documents/presidency-programs/2020-2021-polish)

[2] Under the Trump presidency, the US foreign policy approach was more resident from European security affairs, however, the Biden administration made clear its support for “continued US-EU engagement Eastern Europe, and the Western Balkans.

[3] Followed by the Gazprom groupings, countries of Western Europe: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Great Britain, Greece, Italy, Netherlands, Switzerland + Turkey.

(http://www.gazpromexport.ru/en/statistics/)

[4] The Visegrad Countries declared their common position on conflicts several times, however, did not issue a Russia-specific statement in this context.

[5] Among the V4, Poland has the closest economic ties with Russia. However, within the Group, Poland was the only supporter of the EU economic sanctions imposed against Russia in connection with the 2014 crisis in Eastern Ukraine.

[6] Slovakia was the only V4 country that did not express its solidarity by expelling Russian diplomats in reaction to the 2018 Skripal poisoning.

(https://spectator.sme.sk/c/20790104/slovakia-will-not-expel-russian-diplomats.html)

[i]GRIESSIER, Christina: „The V4 Countries’ Foreign Policy concerning the Western Balkans.” In: Politics in Central Europe, Vol. 14, Issue 2., 09.2018., p.147. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327722760_The_V4_Countries'_Foreign_Policy_concerning_the_Western_Balkans (03.04.2021)

[ii] OROSZ, Anna: „The Western Balkans on the Visegrad Countries’ Agenda.” E-2017/39., p.7.,

https://kki.hu/assets/upload/39_KKI_Policy_Brief_V4-WB_Orosz_20171214.pdf (13.14.2021)

[iii]GRIESSIER, Christina: „The V4 Countries’ Foreign Policy concerning the Western Balkans.” In: Politics in Central Europe, Vol. 14, Issue 2., 09.2018., p.143. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327722760_The_V4_Countries'_Foreign_Policy_concerning_the_Western_Balkans (03.04.2021)

[iv] „Declaration of Prime Ministers of the Czech Republic, the Republic of Hungary, the Republic of Poland and the Slovak Republic on cooperation of the Visegrad Group countries after their accession to the European Union, 12 May 2004.” https://www.visegradgroup.eu/2004/declaration-of-prime (03.04.2021)

[v] „The Bratislava Declaration of the Prime Ministers of the Czech Republic, the Republic of Hungary, the Republic of Poland and the Slovak Republic on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the Visegrad Group.” 15.02.2011., https://www.visegradgroup.eu/2011/the-bratislava (03.04.2021)

[vi] V4 Presidency Programs https://www.visegradgroup.eu/documents/presidency-programs (03.04.2021)

[vii] „Guidelines on the Future Areas of Visegrad Cooperation.” https://www.visegradgroup.eu/cooperation/guidelines-on-the-future-110412 (01.04.2021)

[viii] „Guidelines on the Future Areas of Visegrad Cooperation.” https://www.visegradgroup.eu/cooperation/guidelines-on-the-future-110412 (01.04.2021)

[ix] VÉGH, Zsuzsanna: „Visegrad Development Aid In the Eastern Partnership Region.” Centre for Eastern Studies, p7., https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/177657/visegrad_development_aid.pdf_-_adobe_acrobat_pro.pdf (12.04.2021)

[x] BUGAJSKI, Janus: „The Visegrad Saga: Achievments, Shortcomings, Contradictions.” In: Foreign Policy Review, Institue for Foreign Affairs and Trade, 2017., p.9., https://kki.hu/assets/upload/FPR_2017.pdf (01.04.2021)

[xi] „2005/2006 Hungarian Presidency” Presidency Program. https://www.visegradgroup.eu/documents/presidency-programs/2005-2006-hungarian-110412 (08.04.2021)

[xii] „The Visegrad Group stands ready to promote the integration of the countries of the Western Balkans.” 2009. https://www.visegradgroup.eu/2009/the-visegrad-group (01.04.2021)

[xiii] European Energy Security Strategy 04.05.2014., https://www.europex.org/eulegislation/eu-energy-security-strategy-2/ (13.04.2021)

[xiv] „EU-U.S. LNG Trade. U.S. liquefied natural gas (LNG) has the potential to help match EU gas needs.” European Commission, 2020., https://ec.europa.eu/energy/sites/ener/files/eu-us_lng_trade_folder.pdf (13.04.2021)

[xv] „Three Seas Story.” https://3seas.eu/about/threeseasstory (13.04.2021)

[xvi] „President Donald J. Trump on the 2018 Three Seas Initiative.” In: U.S. Embassy in Romania, 17.09.2018., https://ro.usembassy.gov/president-donald-j-trump-on-the-2018-three-seas-initiative/ (12.04.2021)

[xvii] „US Secretary of State Antony Blinken expressed US support for the Three Seas Initiative.” https://3seas.eu/media/news/us-secretary-of-state-antony-blinken-expressed-us-support-for-the-three-seas-initiative (10.04.2021)

[xviii] „Congratulatory Message on the 30th Anniversary of the Visegrád Group (V4).” Press Statement, U.S. Department of State, 09.02.2021., https://www.state.gov/congratulatory-message-on-the-30th-anniversary-of-the-visegrad-group-v4/ (10.04.2021)

[xix] VINOIS, Jean-Arnold: „Energy infrastructure priorities for 2020 and beyond.” Directorate-General for Energy, European Commission, p.7., https://eepublicdownloads.entsoe.eu/clean-documents/pre2015/news/SDC_Workshop/2.110110-Jean-Arnold_Vinois-EIP_presentation_for_ENTSO-E_Workshop.pdf (09.04.2021)

[xx] „Declaration of the Budapest V4+ Energy Security Summit.” 2010. https://www.visegradgroup.eu/2010/declaration-of-the (09.04.2021)

[xxi] NOSKO, A., ORBÁN, A., PACZYŃSKI, W., FILIP ČERNOCH, F., JAKUB JAROS, J.: „Energy Security. Policy Paper” In: Visegrad Security Policy Paper, p.5. https://www.visegradgroup.eu/download.php?docID=139 (02.04.2021)

[xxii] „Gas supplies to Europe. Delivery statistics.” Gazprom Export, 2019. http://www.gazpromexport.ru/en/statistics/ (02.04.2021)

[xxiii] ROMANOWSKA, Aleksandra: „V4 countries towards Russian aggression against Ukraine.” In: The Warsaw Institute Review, 24.09.2018., https://warsawinstitute.org/v4-countries-towards-russian-aggression-ukraine/ (02.04.2021)

[xxiv] „Danko: Sanctions against Russia 'useless'.” https://www.visegradgroup.eu/news/danko-sanctions-against (10.04.2021)

[xxv] ZGUT, E., SIMKOVIC, J., KOKOSZCSYNSKI, K, HENDRYCH, L.: The V! will never agree on Russia.” In: Euractiv, 03.03.2017., https://www.euractiv.com/section/central-europe/news/the-v4-will-never-agree-on-russia/ (05.04.2021)

[xxvi] RACZ, Andras: „The Visegrad Cooperation: Central Europe divided over Russia.” In: Dans L'Europe en Formation 2014/4, p.29., https://www.cairn.info/revue-l-europe-en-formation-2014-4-page-61.htm (05.04.2021)

[xxvii]„HRC28: Czech Republic speaks on human rights in China, Russia, Azerbaijan.” In: The Permanent Mission of the Czech Republic to the United Nations Office and other International Organizations at Geneva, 28.08.2019., https://www.mzv.cz/mission.geneva/en/human_rights/human_rights_council/hrc28_czech_republic_speaks_on_human.html (06.04.2021)

[xxviii] „Foreign minister praises Hungary's strategy of opening up to the East.” In: About Hungary, 20.02.2020., http://abouthungary.hu/news-in-brief/foreign-minister-praises-hungarys-strategy-of-opening-up-to-the-east/ (12.04.2021)

[xxix] „Russia, Hungary to expand energy cooperation.” SPIEF’21, St. Petersburg International Economic Forum., https://forumspb.com/en/news/news/rossiya-i-vengriya-rasshiryat-vzaimodeystvie-po-energeticheskomu-treku/ (14.04.2021)

[xxx] NYYSSONEN, H., METSALA, J.: „Liberal Democracy and its Current Illiberal Critique: The Emperor’s New Clothes?” In: Europe-Asia Studies, Vol.73, 2021, Issue 2. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09668136.2020.1815654 (15.14.2021)

[xxxi] „Slovakia's Pursuit of Better Relations with Russia” In: The Polish Institute of International Affairs Bulletin, 18.09.2019., https://pism.pl/publications/Slovakias_Pursuit_of_Better_Relations_with_Russia (12.04.2021)