Kutatás / Geopolitika

Where to next? No signing of Swiss-European Union framework agreement

Where to next? No signing of Swiss–European Union framework agreement

Virág Lőrincz

After seven years of negotiation with the European Union, the Federal Council of Switzerland (the executive power) rejected to sign the Institutional Framework Agreement (IFA) on 26 May 2021, which was meant to create a horizontal governance framework by covering the major bilateral agreements between the parties. There are a few sensitive issues behind the refusal that hampered the progress, including wage protection, state aid rules and social security issues connected to the right of free movement of citizens. As the EU intends to assess the existing bilateral agreements on a case-by-case basis, the first non-upgraded domain is medical device equivalence.

Swiss–EU relations: a “bilateral path”

The geographic location of Switzerland explains the importance of its political and economic relations with the EU. It was a founding member of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) and it submitted its application for accession to the EU for the first time in 1992. However, the membership of the European Economic Area (EEA) was rejected in a referendum by 50.3%, and thus the negotiations for joining the EU were suspended. After two subsequent unsuccessful attempts (1997, 2001), the Swiss Parliament officially withdrew its application to join the EU.[1] Still, it continued to deepen its relations with the EU by signing contractual agreements on areas of mutual interest.

Before 1999, the cooperation had been organised around three main domains, including the creation of a free trade zone for industrial products (1972), opening up parts of the Swiss–EU insurance market (1989) and regulating the trade of goods between the parties (1990).[2] Afterwards, the bilateral cooperation became governed by two major packages of agreements (Bilaterals I[3], signed in 1999 and Bilaterals II[4], signed in 2004) covering, inter alia, the free movement of persons and the participation in the Schengen and the Dublin Treaties. After 2004, the cooperation was further broadened, covering Switzerland's other areas of interest, such as enhanced information and intelligence sharing via Europol and cooperation with the European Defence Agency (EDA). Currently, more than 120 bilateral agreements regulate Swiss–Eu relations.[5]

The point of the “bilateral path” is that no sovereign rights can be transferred to EU institutions but implemented only by remaining contract partners. Switzerland shows solidarity with the EU via contributions to specific projects supporting the new member states, and thus reducing social and economic inequalities within the EU.[6]

Trade relations

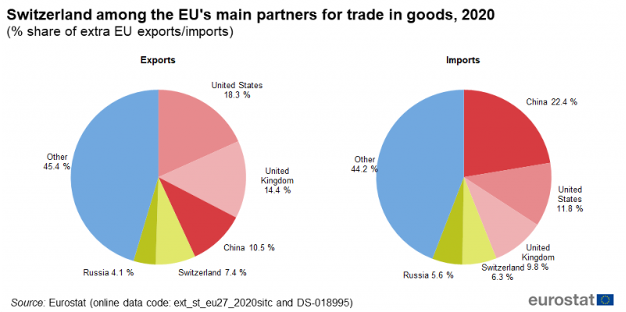

As Switzerland earns its every third franc through trading with the EU, it is no exaggeration to say that the EU is its most important economic partner, whereas Switzerland is the fourth trading partner of the EU after the USA, China and the UK. They are also among each other’s top foreign investment destinations. Swiss export products mainly contain chemicals, medical products, machinery, watches and instruments. As for import from the EU, commercial service constitutes the most important sector. In the last three years (from 2018 to 2020) EU imports of goods were always around a €100 billion, and the exports around €150 billion.[7] Figure 1 shows Switzerland’s position among the EU’s most important trading partners, by showcasing the share it holds in EU exports and imports.

Figure 1: Switzerland among the EU’s main trading partners for trade in goods 2020, Source: Europa.eu[8]

The basis of the close relationship is the Free Trade Agreement (1972)[9] which allows the trade of industrial products free of customs and quotas. At this level of economic cooperation, both parties can determine their external customs and tariffs towards third countries independently.

The dismantle of technical barriers of trade between Switzerland and EU member states is guaranteed by the Mutual Recognition Agreement (2002), which is operational for numerous sectors from machinery to explosives for civil use. The agreement makes trade quicker and eliminates double testing costs. However, without reaching an agreement on the institutional framework, the MRA, including its chapter on medical devices, will not be updated either, as it is one of the existing treaties with the EU.

According to a 2015 survey, conducted by the Swiss State Secretariat for Economic Affairs, the loss of the bilateral agreements would cause severe damages and a decrease in Swiss economy. It would reduce the country’s GDP by 460 billion to 630 billion francs for the period between 2018 and 2035.[10]

The Institutional Framework Agreement

The objective of the Institutional Framework Agreement (IFA) was to make the bilateral cooperation more transparent and simplify it by replacing the more than a hundred agreements with an overarching treaty. It would also stabilise the already existent bilateral agreements and provide room for future ones. On the contrary, the bilateral agreements have to be updated regularly and they are not so dynamic either. They also lack supervisory provisions and effective dispute settlement mechanisms. To address these problems, the EU and Switzerland launched negotiations on an institutional framework agreement on 22 May 2014.[11]

The path to agreement

The direct underlying cause behind the opening of negotiations on a broader institutional framework agreement was the Swiss immigration quota referendum in 2014. By 50.3% voting in favour of bringing back strict quotas for immigration from EU countries, previous Swiss–EU agreements on the protection of people’s right to free movement were violated. Thus, the first round of the negotiations on IFA was interrupted by the implementation of the “Stop mass immigration” popular initiative from 2014 to 2015.[12]

The consultations and ministerial meetings resumed from 2015. The final draft was unveiled at the end of 2018 and Switzerland at first, was given time until the end of 2019 to make its decision, but the negotiations have stalled due to the three concerning issues mentioned earlier. At the end of 2020, the Federal Council defined its position on the clarifications provided by the EU Commission on the aforementioned issues and the further discussions resumed. Swiss President Guy Parmelin and Ursula von der Leyen reviewed the situation in April 2021, which was the last meeting before Switzerland refused to sign the framework agreement.[13]

The demise of the IFA

Despite years of negotiation, the draft was not accepted but rejected by the Swiss Federal Council in May 2021, although all the EU member states supported it. Switzerland, however, formulated three additional demands, which were not acceptable from the side of the EU. These claims included exceptions for Switzerland that even member states are not granted: guarantee for the protection of the country’s traditionally high wages, the revision of state aid rules that would negatively affect the Swiss cantons, and the rejection of EU’s Citizen Right Directive about immigrants’ access to social welfare, which could threaten the Swiss social security system.[14]

The decision, that led to the demise of the IFA, was just as much the consequence of domestic political concerns as of the above-mentioned concrete issues. Although the ideas of sovereignty and Euroscepticism are very strong among Swiss people, it was a bit of a shock for many that the Federal Council threw away years of hard work and without a reference to the Parliament, it refused to come to an agreement with the EU. The decision seems to be in favour of the far-right Swiss People’s Party (SVP) and makes the division between the parties clearer.[15] The outcome of the Council’s decision, however, does not represent the public sentiment, which was rather leaning towards a comprehensive deal. According to a survey, conducted by research institute GFS Bern, about two-thirds of the 2000 people they asked supported the agreement.[16]

Concerns of Switzerland

The Swiss Federal Council announced the need for consultations with the Federal Assembly committees, the parties, and the cantons on the clarification of the IFA draft in December 2018. As the outcomes were unveiled in the next summer, the issues causing concerns were already defined in 2019. Since then, no acceptable clarification or solution was revealed.

According to an overall evaluation about the possible outcomes of the framework agreement by the Swiss Federal Council, the draft shed light on substantial differences between the EU and Switzerland in certain key points. Thus, in its final decision the Council decided not to sign the agreement, and by that, sent the draft to a dead end and suggested to terminate the negotiations instead. In a letter[17] written by the Federal Council to the European Commission about its concerns, there are three open issues, where a balanced outcome satisfactory for both parties is currently not achievable. These are: wage protection, state aid rules and the Citizen’s Right Directive.

Wage protection

Switzerland is known to have one of the highest wage levels in Europe and it is in the intention of the trade unions to keep it this way. It was always the intention of the Federal Council to safeguard wage levels and its understanding that accompanying measures are also necessary to guarantee them. The EU finds some of the accompanying measures are not in conformity with the Free Movement of Persons Agreement (1999) and thus demands their correction. This criticism is rather about proportionality than the measures themselves. This is one of the main reasons why the EU initiated the institutional agreement and also why it was not possible to reach an agreement.[18]

The significance of this issue is that it split up the Swiss pro-European alliance. It was traditionally the left-wing party that supported closer ties with the EU, however the wage protection issue made trade unions oppose the framework agreement.

State aid rules

The fear of Switzerland regarding the EU’s state aid rules is that the possible horizontal effects extend beyond the issues covered by the draft of the IFA before the regulations regarding further issues could be properly updated (for example, the Free Trade Agreement). The EU’s offer of a two-pillar arrangement includes accepting the state aid rules. According to the deal Switzerland would have to apply EU rules, however through an autonomous Swiss surveillance mechanism, which would have the same power during the implementation process as the European Commission.[19]

EU CRD

The Swiss concern regarding the EU’s Citizens’ Right Directive is based on the different implementation of the freedom of movement. Switzerland, as a non-EU member state regulates this issue with the EU under the Agreement on the Free Movement of Persons (AFMP) signed in 1999. In Swiss interpretation it is restricted to workers and their families and could only be conferred to people who provide evidence of a sufficiently stable financial situation. However, in its directive the EU extended the freedom of movement to all EU citizens and thus, created new rights to ensure greater mobility within the integration. The Swiss concern is based on the fact that by incorporating the EU’s CRD in full into the AFMP, it would extend beyond the country’s approach of free movement of workers.[20] For Switzerland, the adoption of the CRD is only possible with explicit exemptions to ensure that it will not include higher social security costs.

Brussels’ reaction

On the day of the unilateral Swiss decision on terminating the negotiations on the IFA, the EU Commission made an official statement.[21] The Commission regrets the Swiss decision on refusing the IFA, as it was meant to ensure the same conditions for all the countries which have access to the EU single market and the sustainability for the further development of the bilateral cooperation. Without the agreement the modernisation of Swiss–EU relations will not be possible, given the expiry process of the fundamental bilateral treaties (Free Trade Agreement, Bilaterals I and II).

However, the Swiss decision should be no huge surprise for the Commission, as comments about the lack of progress in the negotiations on the framework agreement were made since the draft was unveiled in 2018.

The first concrete action of the European Commission was to rule out the import of new Swiss medical devices to the EU. Based on a mutual recognition agreement (2002) a wide variety of goods enjoyed friction-free access to the EU market, including medical devices, but because of the EU’s decision the situation is not like that anymore. The next strike came in July, when the Commission declared Switzerland as a “non-associated third country under the EU Framework Programme for Research and Innovation of Horizon Europe”, or shortly the “Horizon Programme”. By that, Swiss researchers are barred from the funding opportunities.[22]

Future prospects

As it could be expected, pro-European movements have gained strength in the aftermath of the events in May. The group called Opération Libero together with the Swiss Green party is planning to launch an initiative to make the Federal Council reach an agreement with Brussels in the near future.[23]

“We are starting a new chapter in relations between Switzerland and the EU” – said Swiss President Guy Parmelin shortly after the decision was made.[24] To back this up, the Federal Council proposed further regular, high-level political dialogue with the EU to continue the good bilateral relations between the parties. In November 2021, six months after the failure of the negotiations about the IFA, the Swiss foreign minister and the vice-president of the European Commission met in Brussels to launch further political dialogue. However, the meeting was characterized by mutual misunderstandings and lack of prospects. It is becoming increasingly obvious that the two have different ideas about the basis of their relationship.

The EU’s intention is clearly to oblige Switzerland to a closer cooperation in exchange for letting it into the EU’s single market, whereas the leeway of the Swiss government is mostly determined by domestic considerations. Since the four major parties of the country are deeply divided on this issue, and the far-right Swiss People’s Party, which is the biggest of all, strongly opposes closer European cooperation, it is unlikely that substantial progress will be achieved in the Swiss EU policy before the federal elections in autumn 2023, in order to avoid undermining party cohesion.[25] Despite all disagreements, the parties were committed to continuing the political dialogue on a ministerial level in January 2022. How the future relationship will evolve is largely dependent on the willingness of the EU and on the Swiss domestic developments.

While the political dialogue is going on, there are two things that the Swiss government can do. Firstly, it can convince the parliament to pay overdue contributions to cohesion funding, and by that not just relieve tensions with its biggest trading partner but also remove one barrier to Horizon Europe. Secondly, it can review and align the domestic legislation with EU standards in all areas that are controlled by bilateral agreements.[26]

Conclusions

Regarding the future, it is the mutual interest of both Switzerland and the EU to pursue the bilateral approach even in default of a framework agreement. Despite the demise of the IFA, Switzerland aims to deepen its ties with the EU and maintain the privileged bilateral relations based on their shared interest. It also trusts that the existing bilateral agreements will be updated in line with the new EU standards to remain applicable. Unfortunately, status quo is no longer a solution as it would require both parties’ accordance. The EU, however, made its intentions about not updating existing agreements clear. Without further agreements, the quality of the Swiss-EU relation could fall far below than it is now.

The urging importance for reaching an agreement on an overarching treaty is the emerging risk that Switzerland will be blocked out from new forms of access to the single market and, as time passes, more and more currently existing accords will expire. The crisis in the bilateral relations will affect Swiss economy more seriously than the EU because the latter is less dependent on bilateral trade relations. Switzerland has a strong interest in maintaining good relations with the EU, since it enjoys a very special status: it has access to the European single market and in the meantime it can preserve its full sovereignty.

Bibliography

AMMANN, János: Worlds apart: Switzerland and EU keep talking past each other. https://www.euractiv.com/section/economy-jobs/news/worlds-apart-switzerland-and-eu-keep-talking-past-each-other/ (2022. 05. 01.)

CHURCH, Clive H.: Switzerland is facing a dual crisis iver its relations with the EU. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2021/06/29/switzerland-is-facing-a-dual-crisis-over-its-relations-with-the-eu/(2022. 05. 01.)

Európai Parlament: Az Európai Gazdasági Térség (EGT), Svájc és az északi régió. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/factsheets/hu/sheet/169/az-europai-gazdasagi-terseg-egt-svajc-es-az-eszaki-regio (2022. 05. 01.)

European Commission: Commission statement on the decision by the Swiss Federal Council to terminate the negotiations of the EU – Swiss Institutional Framework Agreement. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/statement_21_2683 (2022. 05. 01.)

European Commission: Countries and regions: Switzerland. https://ec.europa.eu/trade/policy/countries-and-regions/countries/switzerland/ (2022. 05. 01.)

GOULARD, Hortense: Switzerland withdraws application to join the EU. https://www.politico.eu/article/switzerland-withdraws-application-to-join-the-eu/ (2022. 05. 01.)

Initiative launched for vote to a Swiss deal with EU. In: Le News, 05.11.2021. https://lenews.ch/2021/11/05/initiative-launched-for-vote-to-agree-swiss-deal-with-eu/ (2022. 05. 01.)

MEULENBELT, Maarten – LOCKHART, Nicolas – RAJU, Deepak – BETTS, Andreas B.: Herring or cheese? The Swiss/European Union Relationship Without an Institutional Framework Agreement. In: Sidley, 09.2021.https://www.sidley.com/en/insights/publications/2021/09/herring-or-cheese-the-swiss-european-union-relationship-without-an-institutional-framework-agreement (2022. 05. 01.)

Poll finds most Swiss back framework deal with EU. In: Swissinfo, 05.09.2021. https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/poll-finds-most-swiss-back-framework-deal-with-eu/46602662 (2022. 05. 01.)

Staatssekretariat für Wirtschaft SECO: Volkswirtschaftliche Auswirkungen eines Wegfalls der Bilateralen I. https://www.seco.admin.ch/seco/de/home/Aussenwirtschaftspolitik_Wirtschaftliche_Zusammenarbeit/Wirtschaftsbeziehungen/Wirtschaftsbeziehungen_mit_der_EU/wirtschaftliche-bedeutung-der-bilateralen-i/volkswirtschaftliche-auswirkungen-eines-wegfalls-der-bilateralen.html (2022. 05. 01.)

Swiss Confederation Federal Department of Foreign Affairs: Bilateral agreements Switzerland – EU. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/meetdocs/2009_2014/documents/deea/dv/2203_07/2203_07en.pdf (2022. 05. 01.)

Swiss Confederation Federal Department of Foreign Affairs: Institutional agreement between Switzerland and the EU: key points in brief. https://www.eda.admin.ch/dam/europa/en/documents/abkommen/InstA-Wichtigste-in-Kuerze_en.pdf (2022. 05. 01.)

Swiss Confederation. The Federal Council: Annex to instituional agreement press release: outcome of talks between Switzerland and the EU on Citizens’ Rights Directive (CRD), wage protection and state aid issues. https://www.eda.admin.ch/dam/europa/en/documents/abkommen/20210526-mm-europapolitik_beilage-8-3_gespraeche_EN.pdf (2022. 05. 01.)

Swiss Confederation. The Federal Council: Timeline of Siwss – EU relations since 2013. https://www.eda.admin.ch/dam/europa/en/documents/abkommen/20210526-mm-europapolitik_beilage-8-2_chronologie_EN.pdf (2022. 05. 01.)

Swiss immigration: 50.3% back quotas, final results show. In: BBC, 09.02.2014. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-26108597 (2022. 05. 01.)

Swiss scrap talks with EU on cooperation deal. In: Euractiv, 27.05.2021. https://www.euractiv.com/section/global-europe/news/swiss-scrap-talks-with-eu-on-cooperation-deal/ (2022. 05. 01.)

Switzerland among the EU's main partners for trade in goods, 2020 https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=File:Switzerland_among_the_EU%27s_main_partners_for_trade_in_goods,_2020_(%25_share_of_extra_EU_exports_imports).png

Switzerland’s European policy. Bilateral agreements and cooperations since 2004. https://www.eda.admin.ch/europa/en/home/bilaterale-abkommen/ueberblick/bilaterale-abkommen-nach-2004.html (2022. 05. 01.)

Switzerland’s European policy. Bilateral agreements I (1999). https://www.eda.admin.ch/europa/en/home/bilaterale-abkommen/ueberblick/bilaterale-abkommen-1.html(2022. 05. 01.)

Switzerland’s European policy. Bilateral agreements II (2004). https://www.eda.admin.ch/europa/en/home/bilaterale-abkommen/ueberblick/bilaterale-abkommen-2.html(2022. 05. 01.)

Switzerland’s European policy. Bilateral agreements until 1999. https://www.eda.admin.ch/europa/en/home/bilaterale-abkommen/ueberblick/bilaterale-abkommen-bis-1999.html (2022. 05. 01.)

Switzerland’s European policy. Free trade. https://www.eda.admin.ch/europa/en/home/bilaterale-abkommen/ueberblick/bilaterale-abkommen-bis-1999/freihandel.html (2022. 05. 01.)

The Federal Council: Institutional agreement between Switzerland and the European Union. https://www.eda.admin.ch/dam/europa/en/documents/abkommen/20210526-brief-BR-vdL-InstA_EN.pdf (2022. 05. 01.)

WALTER, Stefanie: Quo vadis, Swiss – European Union relations? In: Bruegel, 07.06.2021. https://www.bruegel.org/2021/06/quo-vadis-swiss-european-union-relations/ (2022. 05. 01.)

Endnotes

[1] GOULARD, Hortense: Switzerland withdraws application to join the EU. https://www.politico.eu/article/switzerland-withdraws-application-to-join-the-eu/ (2022. 05. 01.)

[2] Switzerland’s European policy. Bilateral agreements until 1999. https://www.eda.admin.ch/europa/en/home/bilaterale-abkommen/ueberblick/bilaterale-abkommen-bis-1999.html (2022. 05. 01.)

[3] Switzerland’s European policy. Bilateral agreements I (1999). https://www.eda.admin.ch/europa/en/home/bilaterale-abkommen/ueberblick/bilaterale-abkommen-1.html (2022. 05. 01.)

[4] Switzerland’s European policy. Bilateral agreements II (2004). https://www.eda.admin.ch/europa/en/home/bilaterale-abkommen/ueberblick/bilaterale-abkommen-2.html (2022. 05. 01.)

[5] Switzerland’s European policy. Bilateral agreements and cooperations since 2004. https://www.eda.admin.ch/europa/en/home/bilaterale-abkommen/ueberblick/bilaterale-abkommen-nach-2004.html (2022. 05. 01.)

[6] Swiss Confederation Federal Department of Foreign Affairs: Bilateral agreements Switzerland – EU. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/meetdocs/2009_2014/documents/deea/dv/2203_07/2203_07en.pdf (2022. 05. 01.)

[7] European Commission. Countries and regions: Switzerland. https://ec.europa.eu/trade/policy/countries-and-regions/countries/switzerland/ (2022. 05. 01.)

[8] Switzerland among the EU's main partners for trade in goods, 2020 https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=File:Switzerland_among_the_EU%27s_main_partners_for_trade_in_goods,_2020_(%25_share_of_extra_EU_exports_imports).png

[9] Switzerland’s European policy. Free trade. https://www.eda.admin.ch/europa/en/home/bilaterale-abkommen/ueberblick/bilaterale-abkommen-bis-1999/freihandel.html (2022. 05. 01.)

[10] Staatssekretariat für Wirtschaft SECO: Volkswirtschaftliche Auswirkungen eines Wegfalls der Bilateralen I. https://www.seco.admin.ch/seco/de/home/Aussenwirtschaftspolitik_Wirtschaftliche_Zusammenarbeit/Wirtschaftsbeziehungen/Wirtschaftsbeziehungen_mit_der_EU/wirtschaftliche-bedeutung-der-bilateralen-i/volkswirtschaftliche-auswirkungen-eines-wegfalls-der-bilateralen.html (2022. 05. 01.)

[11] Európai Parlament: Az Európai Gazdasági Térség (EGT), Svájc és az északi régió. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/factsheets/hu/sheet/169/az-europai-gazdasagi-terseg-egt-svajc-es-az-eszaki-regio (2022. 05. 01.)

[12] Swiss immigration: 50.3% back quotas, final results show. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-26108597 (2022. 05. 01.)

[13] Swiss Confederation. The Federal Council: Timeline of Siwss – EU relations since 2013. https://www.eda.admin.ch/dam/europa/en/documents/abkommen/20210526-mm-europapolitik_beilage-8-2_chronologie_EN.pdf (2022. 05. 01.)

[14] WALTER, Stefanie: Quo vadis, Swiss – European Union relations? https://www.bruegel.org/2021/06/quo-vadis-swiss-european-union-relations/ (2022. 05. 01.)

[15] CHURCH, Clive H.: Switzerland is facing a dual crisis iver its relations with the EU. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2021/06/29/switzerland-is-facing-a-dual-crisis-over-its-relations-with-the-eu/ (2022. 05. 01.)

[16] Poll finds most Swiss back framework deal with EU. https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/poll-finds-most-swiss-back-framework-deal-with-eu/46602662 (2022. 05. 01.)

[17] The Federal Council: Institutional agreement between Switzerland and the European Union. https://www.eda.admin.ch/dam/europa/en/documents/abkommen/20210526-brief-BR-vdL-InstA_EN.pdf (2022. 05. 01.)

[18] Swiss Confederation Federal Department of Foreign Affairs: Institutional agreement between Switzerland and the EU: key points in brief. https://www.eda.admin.ch/dam/europa/en/documents/abkommen/InstA-Wichtigste-in-Kuerze_en.pdf (2022. 05. 01.)

[19] Swiss Confederation. The Federal Council: Annex to instituional agreement press release: outcome of talks between Switzerland and the EU on Citizens’ Rights Directive (CRD), wage protection and state aid issues. https://www.eda.admin.ch/dam/europa/en/documents/abkommen/20210526-mm-europapolitik_beilage-8-3_gespraeche_EN.pdf (2022. 05. 01.)

[20] Swiss Confederation. The Federal Council: Annex to instituional agreement press release: outcome of talks between Switzerland and the EU on Citizens’ Rights Directive (CRD), wage protection and state aid issues. https://www.eda.admin.ch/dam/europa/en/documents/abkommen/20210526-mm-europapolitik_beilage-8-3_gespraeche_EN.pdf (2022. 05. 01.)

[21] European Commission. Commission statement on the decision by the Swiss Federal Council to terminate the negotiations of the EU – Swiss Institutional Framework Agreement. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/statement_21_2683 (2022. 05. 01.)

[22] MEULENBELT, Maarten – LOCKHART, Nicolas – RAJU, Deepak – BETTS, Andreas B.: Herring or cheese? The Swiss/European Union Relationship Without an Institutional Framework Agreement. https://www.sidley.com/en/insights/publications/2021/09/herring-or-cheese-the-swiss-european-union-relationship-without-an-institutional-framework-agreement (2022. 05. 01.)

[23] Initiative launched for vote to a Swiss deal with EU. https://lenews.ch/2021/11/05/initiative-launched-for-vote-to-agree-swiss-deal-with-eu/ (2022. 05. 01.)

[24] Swiss scrap talks with EU on cooperation deal. https://www.euractiv.com/section/global-europe/news/swiss-scrap-talks-with-eu-on-cooperation-deal/ (2022. 05. 01.)

[25] AMMANN, János: Worlds apart: Switzerland and EU keep talking past each other. https://www.euractiv.com/section/economy-jobs/news/worlds-apart-switzerland-and-eu-keep-talking-past-each-other/ (2022. 05. 01.)

[26] WALTER, Stefanie: Quo vadis, Swiss – European Union relations? https://www.bruegel.org/2021/06/quo-vadis-swiss-european-union-relations/ (2022. 05. 01.)