Kutatás / Geopolitika

Military modernisation in Romania (post-1990)

The Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 forced NATO members, especially those in East-Central Europe, to shift their focus back to their military capabilities and defence potentials and to seek out their apparent shortcomings while launching massive modernisation programmes. After assessing the threats of escalation – exacerbated by sharing a long border with Ukraine and having access to the Black Sea – Romanian officials also decided to speed up their ongoing procurements and to significantly increase defence spending in the next decade, even though the Romanian Armed Forces are not in a poor shape relative to the region. Nonetheless, the analysis of three decades of Romanian military modernisation programmes shows that they rarely constituted a priority for lawmakers, and while major rearmament programmes were not uncommon, a lot of the historical potential was squandered through empty promises and leaking pockets.

Post-Warsaw, pre-NATO (1990-2004)

A postcommunist legacy

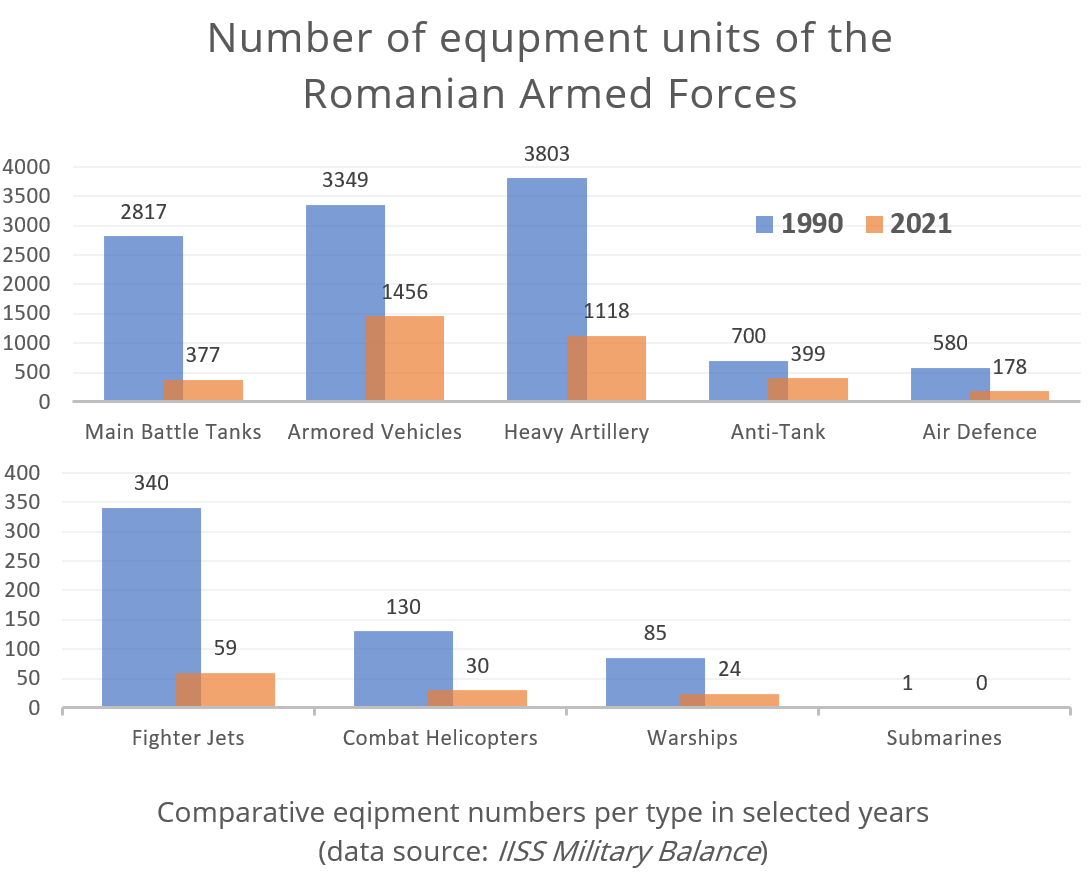

In a regional context, the Army of the Socialist Republic of Romania was a formidable force that stood at 270,000 active personnel at its peak in 1984, second only to Poland (350,000) among the Soviet allies within the Warsaw Pact. Under the leadership of General Secretary Nicolae Ceaușescu (1965-1989), the Romanian military did not only undergo several modernisation programmes with the procurement of the latest Soviet technology, but its foreign suppliers also included the US, the UK, France and Israel, while in the same time much of the weaponry was produced domestically, including armoured vehicles, aircraft and artillery. In the late 1980s, Romania had over 3,000 battle tanks, while the air force consisted of over 1000 aircraft (with almost a third of them being fighter jets).[i] This in turn made Romania a valuable ally to the Soviet Union in terms of military power (albeit the combat readiness of troops was frequently questioned), but the Kremlin also needed to keep in mind the unpredictable nature of Ceaușescu and his susceptibility to break rank from the Warsaw Pact in order to seek the approval of Western leaders (such as the refusal to participate in the suppression of the Prague Spring in 1968 or to adhere to the Soviet boycott of the 1984 Olympics). Nonetheless, The Romanian military participated in various overseas military actions, such as the Angolan and the Mozambique civil wars.

Similarly to other communist countries of Eastern Europe, after that corruption and ineffectiveness had caused long periods of overspending, the slow decline of the Romanian military started to set in during the second half of the 1980s. During a time of soaring inflation, missing basic necessities, food, water and energy rationing (caused, among others, by the repayment of all foreign debts), Romania held a referendum in 1986 to determine whether it should engage in significant military reductions and cut the overall defence spending by 5%. The results came back with 100% support rate, without a single vote to keep the existing spending levels (out of 17.6 million voters with a 99.99% turnout).[ii] Therefore, by the time of the Revolution of 1989, the number of active military personnel has dropped to 210,000 and the downward trend continued throughout the next decade.

Trans-Atlantic aspirations

After the bloody events of 1989 and Romania’s painful but promising early beginnings as a newfound democracy, the army began a long series of multidimensional reforms, aimed to transform Romanian armed forces into a modern conventional army. With the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact and the Soviet Union – as well as the inevitable march of Western supranational institutions toward the eastern half of the continent – created new geopolitical and geostrategic circumstances for Romania and its armed forces, and adequately adapting to them was key for helping the country catch up with the rest of Europe.

The best and most effective way of establishing long-term military modernisation programmes was, of course, through NATO, its affiliated partnerships, and the access to the vast resources of the North-Atlantic community. Therefore, Romania was in fact the first to join NATO’s extended alliance programme Partnership for Peace (PfP), widely viewed as the pathway to full eventual accession, on 26 January 1994.[iii]

Most of the next decade saw both military reforms and diplomatic relations develop simultaneously with the foremost goal of joining NATO. In 1996, the Romanian Parliament officially appealed to all member states requesting support for its aspirations to enter their ranks. In 1997 at NATO’s enlargement summit in Madrid, Romania received candidate status from the Alliance, recognising the progress it had made in fulfilling NATO membership criteria. Two years later, the Kosovo War provided an important opportunity for Romania to build closer cooperation with NATO (and get closer to accession); in 1999 the representatives of NATO and Bucharest had signed agreements to let Western military aircraft use Romanian airspace and three of its airports as long as the operations in Serbia continue, as well as provided free transit for Czech and Polish peacekeeping units through its territory. Learning from the diplomatic benefits, in 2001 Romania once again declared to join NATO’s “war on terror” as a de facto NATO ally, and a year later it began its official accession talks, which – after lengthy diplomatic negotiations – culminated in becoming a full member on 29 March 2004, along with six other post-communist countries as part of the biggest enlargement wave in the Alliance’s history.[iv]

As mentioned above, during this time, Romania also engaged in various military reforms to fulfil the NATO membership criteria, yet most of these only touched the inner structures, the decision-making processes, the civilian leadership and certain financing aspects of the army, in line of the four main principles outlined at the start of this period: transparency, visibility, continuity, and selective financing.[v] By the early 2000s, Romania had several accomplishments to show off. It managed to downsize its active duty strength by 60%, eliminated large portions of its financially burdensome structures, significantly improved its command-and-control, and established a NATO compatible communications system, among others.[vi] But while the structural reforms required by NATO, and specified later by its Membership Action Plan (MAP), were rigorously followed on paper, Romania seriously lagged behind in two interconnected areas: the professionalisation of the armed forces and the modernisation of the equipment. [vii]

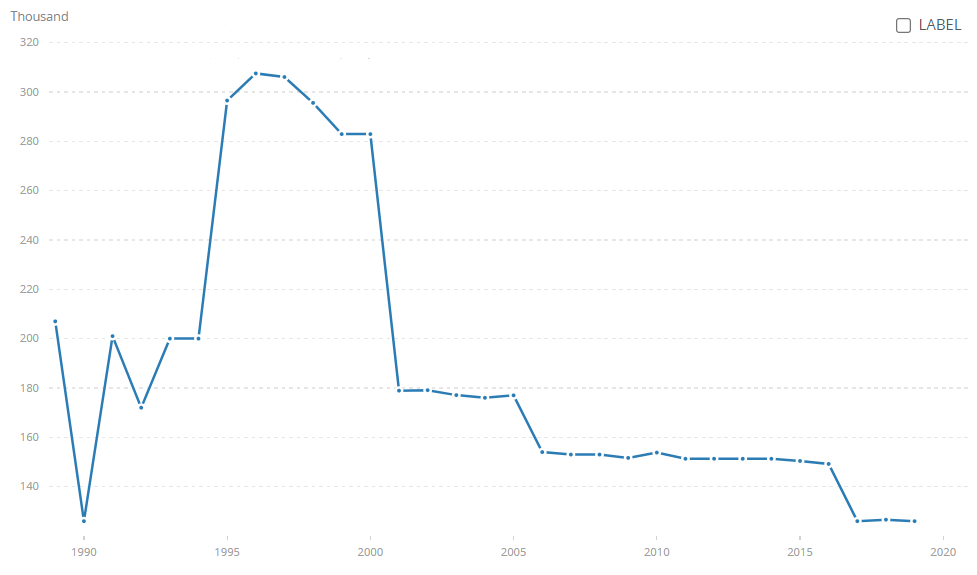

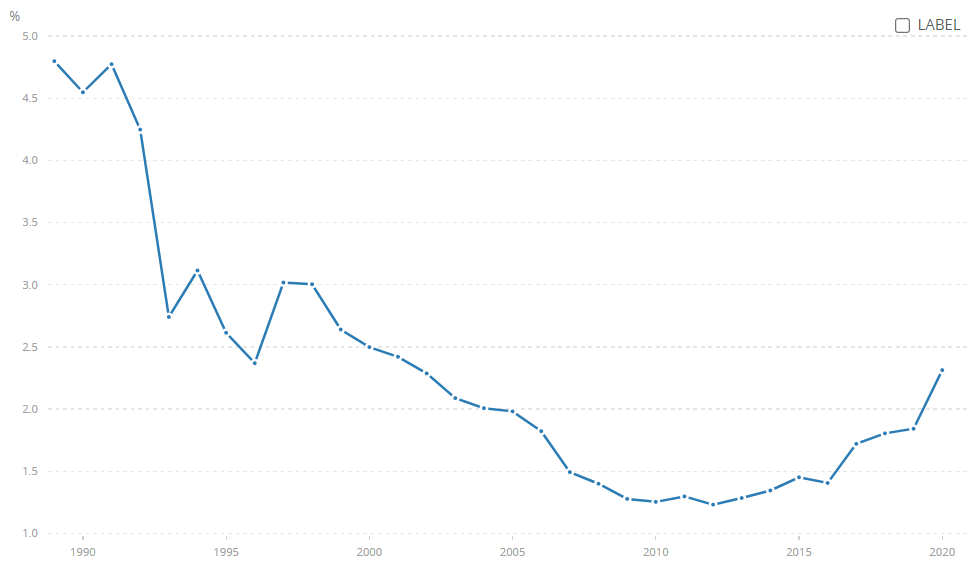

During this time, obligatory military service was still in place in the country, while – due to the costly transition to free-market democracy – defence spending slowly plummeted and little to no funds remained for the acquisition of new equipment. What is more, much of the old Soviet and homemade technology was decommissioned due to the maintenance costs, while the previously quite competitive Romanian arms manufacturing industry all but ceased to exist. If we look at the numbers, during this period the defence spending (relative to GDP) dropped from 4.8% in 1991 to 2% in 2004,[viii] while even if the number of active personnel nearly halved to reach 170,000 troops (compared to the more than 300,000 in 1996),[ix] the army was still made up of conscripts instead of paid professionals. The urgent need to professionalise the army was of course recognised by both civil and military officials – arguing that if the country was to acquire modern weaponry, it would need specifically trained personnel to use it, people who spend more time in the army than a couple of months and are also materially motivated[x] – yet the funds were simply insufficient for the time being. Therefore, Romania entered NATO with only the promise of outlawing obligatory service as soon as possible (it amended the constitution to allow such a move in 2003) and building a conventional army in the following years.

The challenges and benefits of Atlanticism (2004-2014)

Getting up to speed with NATO

As soon as Romania officially joined NATO, it started simultaneous military modernisation programmes in the two areas mentioned above. Plans were laid out to end obligatory service and replace conscripts with professionals within a few years, while massive deals were made for arms shipments to fill up the blank spots in the weaponry.

Regarding professionalisation, the Romanian parliament voted in 2005 to gradually phase obligatory military service out. Debates about the final number of professional soldiers after the transformation were still there, dragging out the whole process. Finally, in 2006, the law on ending obligatory service in peacetime was finalised, outlawing it as of 1 January 2007.[xi] The plan – laid out before the NATO accession – to simultaneously reduce the number of military personnel was to be completed in two steps. The first stage envisaged the total military personnel at 90,000 by 2007 (75,000 soldiers, 15,000 civilian staff), and a further reduction to a total of 80,000 by the end of 2015.[xii] With slight modifications, the number of active military personnel was set at just above 150,000 by 2007, and at 126,000 by 2017 (administration included).[xiii]

Romanian armed forces personnel, in thousand people, 1989-2019

(Source: World Bank)

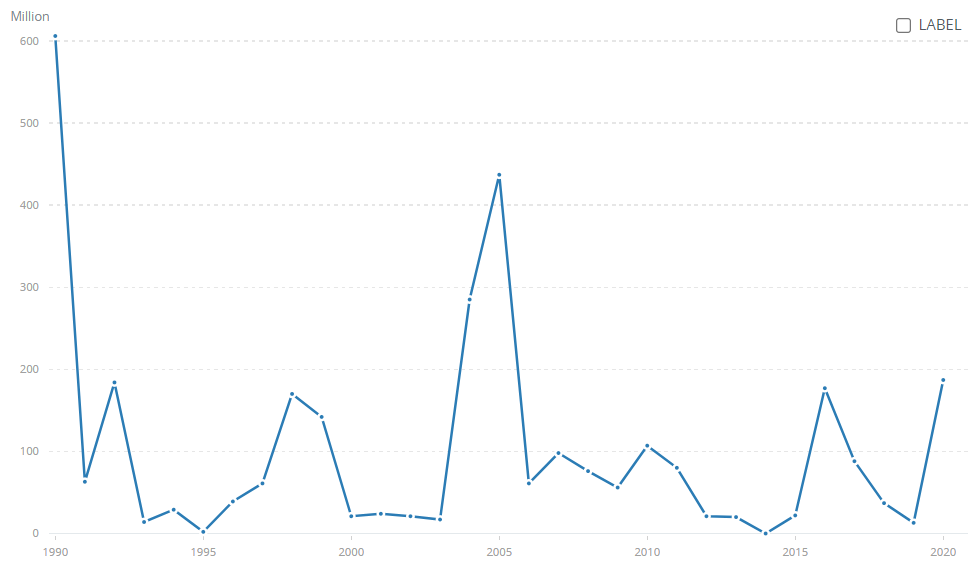

If we look at the acquisition programmes, we can also see the arms imports increasing significantly in the years after NATO accession. According to the Romanian MoD, the main priority in terms of equipment modernisation was given to the air force. Yet, for the moment, no new purchases had been made, instead – by contracting several western arms manufacturers – Romania began to modernise its already existing aircraft park in order to achieve high levels of interoperability with standard NATO equipment. Because its primary fleet of MIG-21 Lancers (110 out of the 170 total) had already been upgraded by the Israeli AEROSTAR before the NATO accession, the MoD hired the same company to refurbish its old IAR 93 attack and anti-tank helicopters with modern sensors and weaponry.[xv] The same tactics were employed regarding the land forces’ equipment: Romania did not buy new battle tanks, instead opted for the continuing modernisation of its domestically produced TR-85s. By 2010, Romania had converted 54 of its more than 600 TR-85s into the new TR-85M1 Bison (modelled after the French Leclerc), which are fully compatible with NATO weapons and communication systems.[xvi]

Regarding the modernisation of the Romanian Navy, two high-level acquisitions happened during this time, both from the British Royal Navy. Ahead of NATO accession, Romania bought two decommissioned Broadsword-class frigates – the HMS Coventry (renamed King Ferdinand) and the HMS London (Queen Maria), both constructed in the early 1980s and used in the first Gulf War – to be refurbished with the help of the Alliance by the end of 2005. Apart from the Timișoara-class frigate, Mărășești (constructed domestically in 1985), these two are the largest battles ships of the Romanian Navy to this day, and definitely the most well-equipped.[xvii] It is worth noting, that Romania paid scrap value, only £200,000 for the ships themselves, and a whopping £115.8 million (around $200 million today) for the refurbishment by the British company BAe Systems, even though several Dutch frigates were also offered to Romania for 20 million apiece and in working condition without the need to upgrade them. Later, the scandal broke out in both countries, and the British police suspected the Bae of bribing Romanian MoD officials with as much as £8 million to accept the deal, but the investigation was subsequently dropped.[xviii]

Romanian arms imports, in millions of dollars, 1989-2020

(Source: World Bank[xix])

Dilemmas of burden-sharing

The enhanced heterogeneity within NATO – brought by the admission of the Eastern and Central European countries – with regards to defence capabilities, geographical location, industrial power, and strategic risks did not only pose problems for the Alliance in terms of decision-making (since all decisions have to be unanimous) but also presented new challenges in terms of burden-sharing.[xx] Upon accession, all members of NATO pledge to spend 2% of their annual GDP on defence purposes, yet for the relatively underdeveloped economies of the East (compared to the Western members), different priorities were always likely to overshadow the fulfilment of such vows.

Furthermore, it was not only a question of developing economies, but many other factors also influenced the debate, such as the difference between the members’ R&D capabilities, the declining threat of Russia during the 2000s, or their will and power to run military operations overseas (which is also derived from the political and material benefits – real and perceived – that each member can gain from the participation in joint missions.) Spending on combat is much more expensive than just on peace-keeping or humanitarian missions, albeit politically more rewarding as well, but each member is bound to have different motivations. This in turn created a “two-tiered alliance of contributors’”[xxi] during the wars on terror (primarily in Iraq and in Afghanistan), which gradually set the stage for decreasing group cohesion and mounting internal tensions.

Regarding Romania, we can more or less observe the same trends in defence spending as in other eastern members of the Alliance. Before NATO accession, Romania purposefully maintained its defence spending above 2% of its GDP, but it quickly started to decrease in the following years: it reached 1.5% by 2007, and its all-time low of 1.2% by 2012.[xxii] At the same time, the average GDP-relative defence spending of the whole of the NATO (except the United States) also went under 1.5% (as it reached its historic low at 1.4% in 2015),[xxiii] which made officials worry about the future of the Alliance. In fact, one of the most important talking points of the 2010 Lisbon Summit was the need for “recommitment” to the 2% defence spending pledge. Equal burden-sharing and simultaneous technological development were identified as primary goals of NATO, since without them the interoperability of the members’ equipment and personnel would soon disappear – ending joint training and combat missions, and making the core concept of political solidarity unable to be turned into action.[xxiv]

Yet, the extensive and costly reforms Romania went through around and after NATO accession – meaning the modernisation of its outdated weaponry, transportation and communications systems, restructuring its entire command-and-control, as well as the entire process of professionalisation of the armed forces between 2005 and 2007 – effectively drained the country of further resources to commit to the required levels of defence spending each year, especially after the 2008 financial crash.

Romanian defence spending in percentage of GDP, 1990-2020

(Source: World Bank[xxv])

These factors, along with the fact that Romania consistently scored second lowest in GDP/capita within the EU during this time,[xxvi] as well as the relatively long peaceful period (1999-2014) that the continent witnessed without any armed conflict on its territory, made it look like that the situation will not change anytime soon – unless something happens that would foreshadow the next big geopolitical shift in Europe.

Challenges of a changing world (2014-2022)

Old threats, new perspectives

The eruption of the Ukrainian civil war and the annexation of Crimea by Russia in 2014 served as the first warning shots for NATO and the West in general. After the initial shockwave settled, many of the previously reluctant European members started to gradually increase their defence spending with new arms procurements and overall modernisation programmes. This trend was most observable on the eastern periphery of the Alliance, notably in the Baltics, Poland and Romania, where leaders were the first to feel the changing winds. The 2014 NATO Summit in Wales saw all European members once again recommit to the 2% of GDP in defence spending criteria, and these countries were among the first to actually achieve that goal. Romanian defence spending began to grow in the next couple of years, and in January 2019, Romanian president Klaus Iohannis signed a law to permanently set defence spending above 2% of the GDP. In return, NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg called Romania “an example to be followed by other Allies.”[xxvii]

Consistently with the rise in defence expenditures, from 2015 onward, we see sharp rises in both defence spending and arms imports in Romania, clear signs of serious intentions to follow through with the long-planned modernisation programmes. After a lengthy assessment, the Romanian MoD announced its biggest modernisation project so far in 2017, with 16 separate acquisitions programmes above €100 million and several smaller ones as well, aimed to rearm all three defence branches by 2026. According to the published plans, the country was seeking to acquire 52 fighter jets for the air force, four corvettes and three submarines for the navy, 270 main battle tanks (MBTs) and more than 500 armoured personnel carriers (APCs) for the ground forces, as well as several long and short-range missile defence systems, heavy artilleries, anti-tank weaponry, and new, NATO-compatible 5.56 calibre assault rifles to replace the Soviet 7.62 calibre AK-47s and their derivatives. Out of 24 planned acquisition programmes, by 2019, only three had been completed, seven were ongoing, with another five approved by the parliament, and nine which had already been cancelled or suspended. [xxviii]

For instance, this was the period when Romania finally purchased 17 used F-16 Falcons from Portugal to complement its fleet of aging (and gradually decommissioned) MiG-21 Lancers. While the initial order for 12 fighter jets was approved in 2013, a further five planes were ordered in 2019, for a total of nearly $850 million, furthermore, an additional $175 million contract was signed with the US-based manufacturer Lockheed Martin to upgrade the whole fleet. The final, upgraded F-16s arrived in Romania in early 2021.[xxix] Yet, these 17 jets are still a long way from the desired 52, as outlined above.

Similarly to the modernisation of the air force, Romania planned to replace its old TR-85 battle tanks with more modern equipment. In 2018, the MoD initiated a procurement programme that aimed to buy as many as 60 German-made Leopard 2A5 MBTs,[xxx] but no subsequent order was made, nor did the following issues (2019 and 2020) of the White Paper on Defence mention anything on further development.[xxxi]

For the construction of the four new Gowind-class corvettes, as well as the modernisation of the two existing frigates belonging to the Romanian Navy, the French manufacturer Naval Group was selected in 2019 to sign the contract for $1.35 billion. However, two years later the tender was suspended because of growing evidence of corruption, and the legal battle is still ongoing. If the Naval Group were to be found guilty, the contract would then go to the Dutch Damen to finish the project. Regardless, what is important is that still no new warships have been added to the Romanian Navy.[xxxii]

The single most expensive acquisition programme in the package was that of the seven Patriot air defence systems for nearly $4 billion. The first unit was expected to be delivered by 2019 and become operational by 2020, but instead, it was unveiled for the first time in September 2020, with no newer units added since.[xxxiii] The other flagship project announced in 2017 foresaw the procurement of 54 HIMARS long-range (300 km) surface-to-surface rocket launchers, also from Lockheed Martin for $1.5 billion. So far, only three of them have been purchased and delivered.[xxxiv]

One more project needs to be mentioned, which is not a Romanian acquisition but serves as one of the primary tools for the extended defence capabilities of the whole NATO. In 2011, Romania signed a cooperation agreement with the United States to host the first Aegis Ashore ballistic missile defence system in Eastern Europe, complemented by another later to be installed in Poland, which is capable of intercepting ICBMs with its SM-3 ballistic missiles. The one at Deveselu air base, Romania, became operational in 2016, while the Polish site is running since 2019. The Aegis Ashore, although it was not paid for by Romania, is viewed as the country’s most significant contribution to NATO – not only because of its advanced defensive capabilities but also because of the risks associated with hosting it on a country’s sovereign ground. Since their announcement, Russia has been accusing NATO of violating the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, because of the Aegis systems’ alleged ability not only to fire interceptors of the SM-3 family, but they could be easily converted to be used with a whole range of ICBMs as well. NATO discharged these Russian allegations, saying that only substantive and lengthy modifications would allow that, nonetheless, public debate in both countries on whether these systems make them unnecessary targets in the eyes of Moscow is still ongoing.[xxxv]

Conflict on the horizon

Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the general perceptions of defence capabilities and military modernisation have changed in all NATO member states. The modernisation programmes of the late 2010s across Europe have not nearly proved quick and wide enough to meet the challenge of a possible escalation between NATO and Russia, therefore most members immediately announced new ones, as well as increased their defence spending considerably. This was also the case in Romania, which announced that it will increase its defence budget to 2.5% of the GDP by 2023, which means a significant raise from the current 2.04% in such a short amount of time.[xxxvi]

In terms of military modernisation, Romania started to speed up its previously stalled procurement programmes. In case of the air force, it became clear that significantly more new fighter jets will be needed (than the 17 F-16s), as the time for the complete decommissioning of the entire MiG-21 fleet was fast approaching, set by the Romanian MoD on 15 May 2023. To replace them, Romania signed a deal for two additional squadrons (32 jets) of second-hand F-16s with Norway in June 2022 for $514 million, which would increase the total number to 49, once upgraded by Lockheed Martin and delivered to the country in the coming years. Plans to purchase the Norwegian fighters were announced months before the war broke out – with the possibility of using other suppliers too, such as Denmark, Belgium or the Netherlands – but the invasion undoubtedly prompted lawmakers to follow through with the acquisition as soon as possible.[xxxvii] Furthermore, President Klaus Iohannis announced in February that Romania is also planning to purchase new-generation F-35 Lightning fighters as well, but only upon the decommissioning of the F-16s after 2030.[xxxviii]

In the case of the ground forces, there is still no news on the development of the battle tank procurement programme, but the plan to significantly increase the number of armoured personnel carriers is well underway. Romania signed a contract with GDELS for the manufacturing of 227 Piranha 5 infantry fighting vehicles, to be produced mainly in Switzerland and then assembled domestically. Up until now, 68 Piranhas have been delivered and put into service, with an additional 32 arriving by the end of 2022. However, to speed up production, Romania signed a joint venture between GDELS and a Bucharest-based mechanical plant (UMB) after the invasion of Ukraine, to completely produce and assemble the remaining 133 APCs inside the country.[xxxix]

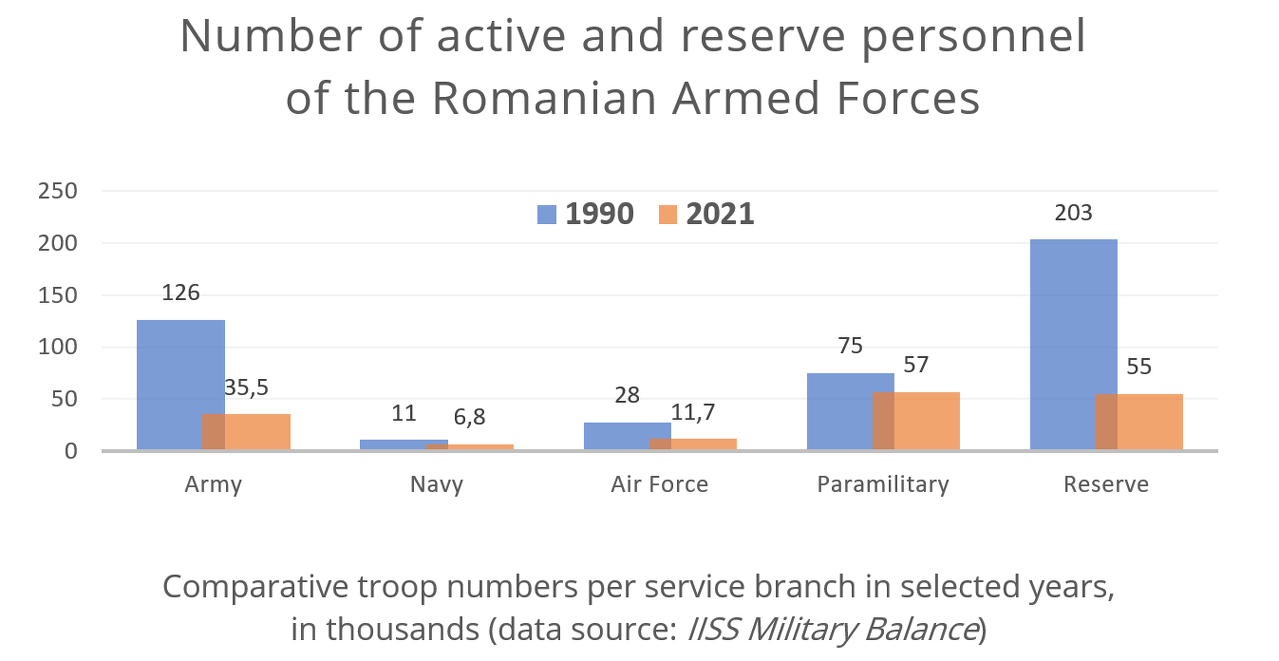

Overview of three decades of development

Finally, if we were to see the current state of the Romanian military (in terms of manpower, firepower and mobility), perhaps it would serve us best to compare it to the 1990 levels, as well as the current state of militaries in neighbouring countries. Comparing the data from the IISS’ Military Balance,[xl],[xli] we get the following figures, first on Romanian military personnel across all service branches.

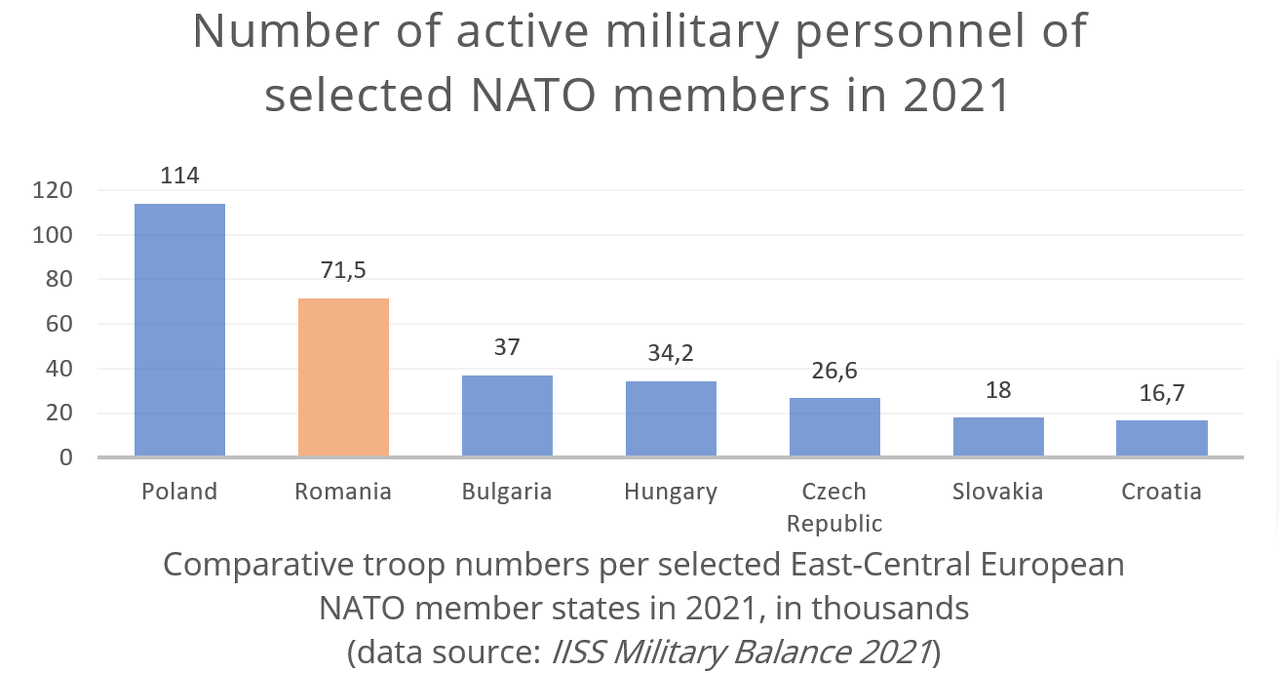

We see that troop numbers have significantly decreased over the last three decades across the board. Nonetheless, we need to note, that this downsizing corresponds with wider trends within Eastern Europe, as well as the professionalisation of the whole of the armed forces. While 107,000 troops of the 163,000 active personnel (66%) were conscripts in 1990, today’s Romanian army is entirely made up of professionals. We can add another perspective by comparing Romania’s armed forces to neighbouring East-Central European NATO members (of comparable size, with a population of four million or bigger). It is clear that Romania still has a relatively large military among the (non-Soviet) post-communist NATO members, second only to Poland’s (whose population is almost twice the Romanian).

Now, if we look at firepower and mobility, we will see that the size of Romania’s weapon inventory was also reduced, but we have to keep in mind that it has been modernised as well – replacing a lot of the decommissioned Soviet technology with newer, Western equipment. One good example is the fighter jets (today’s primary force is a squadron of F-16s instead of the Soviet MiG-21s, with two other squadrons awaiting delivery), and another is the warships (Romania had four times as many combat-capable navy vessels in 1990, but only one frigate, while now it has three).

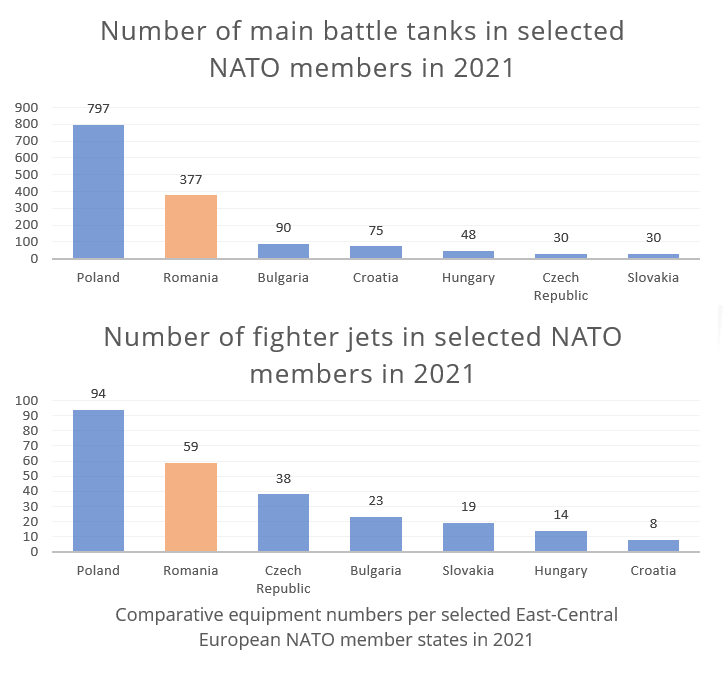

Finally, if we compare Romania’s primary weaponry (using only two metrics, the most important, yet comparable ones – MBTs and fighter jets – since landlocked countries do not have navies) to the same group of countries as above, we get a similar result in terms of Romania’s relative place among the group.

It is clear, that while Romania’s modernisation programmes have been meeting difficulties in the past, the country kept its relatively strong place within the region, in terms of manpower, firepower and mobility alike.

Conclusions

The democratic Romania inherited a formidable military after the Revolution of 1989, with a relatively large force of active personnel and huge numbers of Soviet weaponry. During the 1990s, however, as the old technology started to decay and had been gradually decommissioned, Romania was unable to allocate enough funds for replacements. Due to budgetary reasons, the size of the armed forces was also reduced, as well as the command and control was entirely restructured, but significant modernisation programmes and personnel reforms did not occur until Romania’s NATO accession in 2004.

Right after it became a member of the North Atlantic Alliance, however, Romania launched a number of new acquisition programmes and began to gradually professionalise its armed forces, outlawing conscription entirely by 2007. These processes called for further downsizing and restructuring, and even though by doing so the country managed to transform the military into a more cost-effective conventional army, it struggled to live up to its NATO commitment of keeping the defence budget above 2% of the GDP. Due to unwise procurement choices (likely tied to suspected high-level corruption cases) and the relative peace Europe experienced, officials prioritised other issues and downplayed any potential external threats to NATO during that time. As a result, over the first ten years after the accession, Romania’s defence spending plummeted to its all-time low.

The second half of the 2010s, however, brought about a gradual revival of Romanian military modernisation programmes – a trend witnessed in other European NATO allies as well – due to the shifting geopolitical situation in the East (with the annexation of Crimea in 2014) and the Alliance’s subsequent political pressure aiming to get Europeans to spend more on defence. By 2019, Romania finally achieved the 2% GDP milestone again, and was already in the midst of its biggest ever modernisation initiative – a package of over two dozen acquisition and upgrade programmes – aimed to completely overhaul the equipment of the armed forces within the 2017-2026 timeframe. While the ambitions were certainly higher and the intent more serious, around half of these programmes encountered the same problems as those in the mid-2000s, which resulted in cancelling or suspending them indefinitely. Yet, the 2022 invasion of Ukraine shifted the focus back to the country’s defence capabilities and prompted politicians to reconsider some previously dropped or stalled deals, to make plans for new ones and to increase the defence budget significantly over the next few years.

All factors taken into account, Romania did manage to transform its armed forces from a conscription-based military with untrained personnel, ineffective administration and outdated Soviet weaponry into a modern conventional army with professionals trained on western equipment. While it is true that due to complex political reasons the past military modernisation programmes did not fully live up to their potential, the Romanian armed forces still managed to keep their former position among the regional militaries in the number of active personnel and equipment alike. If the reforms announced in the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine become completed, Romania will likely be one of the major military powers among the European members of NATO.

Bibliography

- Armed forces personnel, total – Romania. In: World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.TOTL.P1?locations=RO (30.06.22.)

- Arms imports (SIPRI trend indicator values) – Romania. In: World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.MPRT.KD?end=2020&locations=RO&start=1990 (02.07.22)

- BUTIRI, Sorin: Does Romania still need tanks? In: Defense & Security Monitor, 29 October 2020, https://en.monitorulapararii.ro/does-romania-still-need-tanks-1-33968 (11.07.22)

- CHIPMAN, John, et al. (eds.): The Military Balance 1990-1991 – International Institute for Strategic Studies. Brassey’s, London, 1990.

- CHIRILEASA, Andrei: RO army tests HIMARS multiple rocket launchers in simulated attack on Black Sea ships. In: Romania Insider, 14 June 2022, https://www.romania-insider.com/ro-tests-himars-jun-2022 (11.07.22)

- CHIRILEASA, Andrei: Romania's Govt. adopts draft bill for the purchase of 32 F-16 fighters from Norway. In: Romania Insider, 17 June 2022, https://www.romania-insider.com/romania-f16-fighters-norway-purchase (11.07.22)

- COZMEI, Victor: Armele României (I) - Forțele Terestre: Ce arme, tancuri și blindate folosesc acum militarii români. In:Hotnews, 26 April 2019, https://www.hotnews.ro/stiri-defense-23110364-armele-romaniei-fortele-terestre-arme-tancuri-blindate-folosesc-acum-militarii-romani-plus-noi-echipamente-contureaza-pentru-viitor.htm (02.07.22)

- Cronologia relaţiilor România – NATO. In: Ministerul Afacerilor Externe, https://www.mae.ro/node/5346 (29.06.22)

- Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2010-2017),

NATO Public Diplomacy Division Press Release, 29 June, 2017, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/pdf_2017_06/20170629_170629-pr2017-111-en.pdf (04.07.22) - DODGE, Michaela: A Decade of US-Romanian Missile Defense Cooperation:

Alliance Success. In: Real Clear Defense, 19 March 2021, https://www.realcleardefense.com/articles/2021/03/19/a_decade_of_us-romanian_missile_defense_cooperation_alliance_success_768925.html (11.07.22) - DUŢU, Petre (et al.): Profesionalizarea Armatei României în contextul integrării în NATO. Centrul de Studii Strategice de Apărare şi Securitate, Bucharest, 2003.

- HACKETT, James (ed.): The Military Balance 2022 – International Institute for Strategic Studies. Routledge, London, 2022.

- JENNINGS, Gareth: Romania receives final F-16 from Portugal. In: Janes, 26 March 2021, https://www.janes.com/defence-news/news-detail/romania-receives-final-f-16-from-portugal (11.07.22)

- LEIGH, David; EVANS, Rob: We paid three times too much for UK

frigates, Romania says. In: The Guardian, 13 June 2006, https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2006/jun/13/armstrade.bae (02.07.22.) - MARIAN, Mircea; DRĂGAN, Flavia: Calendar 22 Octombrie -18 noiembrie - 15 ani de la desființarea serviciului militar obligatoriu. In: Newsweek, 22 October 2021, https://newsweek.ro/istorie/calendar-22-octombrie-18-noiembrie-15-ani-de-la-desfiintarea-serviciului-militar-obligatoriu (01.07.2022.)

- MARINAS, Radu-Sorin: Romania receives Patriot missiles from U.S. to boost defences. In: Reuters, 17 September 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-romania-defence-usa-patriot-idUKKBN2681K6 (11.07.22)

- McNAMARA, Sally: NATO Summit 2010: Time to Turn Word Into Action. In: The Heritage Foundation, 10 December 2010, https://www.heritage.org/global-politics/report/nato-summit-2010-time-turn-words-action (04.07.22.)

- MIHU, Laurentiu: Cum s-a schimbat România după intrarea în NATO. Armata înainte și după aderare. In: G4 Media, 2 April 2019, https://www.g4media.ro/cum-s-a-schimbat-romania-dupa-intrarea-in-nato-armata-inainte-si-dupa-aderare.html (02.07.22)

- Military expenditure (% of GDP) – Romania. In: World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.XPND.GD.ZS?locations=RO (30.06.22.)

- MUREŞAN, Mircea: Armata României după reuniunea la nivel înalt de la Praga. In: Integrarea euro-atlantică, priorităţi post-Praga. Editura AISM, Bucharest, 2002.

- NATO Partnership for Peace. U. S. Department of State Archive, 19 June 1997, https://1997-2001.state.gov/regions/eur/nato_fs-pfp.html (28.06.22.)

- Nave maritime. In: Fortele Navale Romane, https://www.navy.ro/despre/nave.php (02.07.22.)

- NEAGU, Bogdan: Romania is still committed to buy F-35s, but after 2030. In: Euractiv, 3 February 2022, https://www.euractiv.com/section/politics/short_news/romania-still-committed-to-get-f-35s-but-after-2030/ (11.07.22)

- PAVEL, Cornel: Romanian armed forces transformation. USAWC, Carlisle, 2002.

- Piranha 5 Armored Vehicles To Be Entirely Produced At The Bucharest Mechanical Plant. In: Romania Journal, 15 March 2022, https://www.romaniajournal.ro/society-people/piranha-5-armored-vehicles-to-be-entirely-produced-at-the-bucharest-mechanical-plant/ (11.07.22)

- POPESCU, Ana-Roxana: Romania to increase defence spending to 2.5% of GDP. In: Janes, 3 March 2022, https://www.janes.com/defence-news/news-detail/romania-to-increase-defence-spending-to-25-of-gdp (11.07.22)

- RÂPAN, Florian: Coordonate ale modernizării managementului resurselor de apărare în forţele aeriene – Suport al eficienţei operaţionale. In: Defense Resources Management in the 21st Century. National Defence University, Bucharest, 2007.

- RIVOLIN, Umberto Janin: Global Crisis, Spatial Justice and the Planning Systems:

a European Comparison. In Research Gate, July 2016, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/313798739_Global_Crisis_Spatial_Justice_and_the_Planning_Systems_a_European_Comparison (02.07.22.) - Romania canceled Gowind-class corvettes project with Naval Group. In: Global Defense Corp, 22 September 2021, https://www.globaldefensecorp.com/2021/09/22/ooch-romania-cancelled-gowind-class-corvettes-project-with-naval-group/ (11.07.22)

- Romania increased defense spending to 2% of GDP. In: Embassy of Romania to the USA, Romanian Foreign Ministry, https://washington.mae.ro/en/local-news/1432 (11.07.22)

- Romania to buy 60 new main battle tanks. In: Army Recognition, 21 November 2018, https://www.armyrecognition.com/november_2018_global_defense_security_army_news_industry/romania_to_buy_60_new_main_battle_tanks.html (11.07.22)

- Romania, cel mai important dintre viitorii membri ai NATO. In: Adevarul, 20 November 2002, https://www.adevarulonline.ro/romania-cel-mai-important-dintre-viitorii-membri-ai-nato/ (02.07.22.)

- Romania, November 23, 1986: Downsizing of the army, reduction of

armament expenditures by 5%. In: Direct Democracy, 21 January 2019, https://www-sudd-ch.translate.goog/event.php?lang=de&id=ro011986&_x_tr_sl=auto&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en (26.06.22.) - SANDLER, Todd; SHIMIZU, Hirofumi: NATO Burden Sharing 1999-2010: An Altered Alliance. In: Foreign Policy Analysis, Vol. 10, 2014.

- VISAN, George: The Known Unknowns of Romania’s Defense Modernization Plans. In: ROEC, 3 March 2019, https://www.roec.biz/project/the-known-unknowns-of-romanias-defense-modernization-plans/ (11.07.22)

Endnotes

[i] MIHU, Laurentiu: Cum s-a schimbat România după intrarea în NATO. Armata înainte și după aderare. In: G4 Media, 2 April 2019, https://www.g4media.ro/cum-s-a-schimbat-romania-dupa-intrarea-in-nato-armata-inainte-si-dupa-aderare.html (02.07.22)

[ii] Romania, November 23, 1986: Downsizing of the army, reduction of

armament expenditures by 5%. In: Direct Democracy, 21 January 2019, https://www-sudd-ch.translate.goog/event.php?lang=de&id=ro011986&_x_tr_sl=auto&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en (26.06.22.)

[iii] NATO Partnership for Peace. U. S. Department of State Archive, 19 June 1997, https://1997-2001.state.gov/regions/eur/nato_fs-pfp.html (28.06.22.)

[iv] Cronologia relaţiilor România – NATO. In: Ministerul Afacerilor Externe, https://www.mae.ro/node/5346 (29.06.22)

[v] MUREŞAN, Mircea: Armata României după reuniunea la nivel înalt de la Praga. In: Integrarea euro-atlantică, priorităţi post-Praga. Editura AISM, Bucharest, 2002, p. 8.

[vi] PAVEL, Cornel: Romanian armed forces transformation. USAWC, Carlisle, 2002, p. 24.

[vii] DUŢU, Petre (et al.): Profesionalizarea Armatei României în contextul integrării în NATO. Centrul de Studii Strategice de Apărare şi Securitate, Bucharest, 2003, pp. 8-19.

[viii] Military expenditure (% of GDP) – Romania. In: World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.XPND.GD.ZS?locations=RO (30.06.22.)

[ix] Armed forces personnel, total – Romania. In: World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.TOTL.P1?locations=RO (30.06.22.)

[x] DUŢU (et al.), p. 9.

[xi] MARIAN, Mircea; DRĂGAN, Flavia: Calendar 22 Octombrie -18 noiembrie - 15 ani de la desființarea serviciului militar obligatoriu. In: Newsweek, 22 October 2021, https://newsweek.ro/istorie/calendar-22-octombrie-18-noiembrie-15-ani-de-la-desfiintarea-serviciului-militar-obligatoriu (01.07.2022.)

[xii] Romania, cel mai important dintre viitorii membri ai NATO. In: Adevarul, 20 November 2002, https://www.adevarulonline.ro/romania-cel-mai-important-dintre-viitorii-membri-ai-nato/ (02.07.22.)

[xiii] Armed forces personnel. In: World Bank.

[xiv] Ibid.

[xv] RÂPAN, Florian: Coordonate ale modernizării managementului resurselor de apărare în forţele aeriene – Suport al eficienţei operaţionale. In: Defense Resources Management in the 21st Century. National Defence University, Bucharest, 2007, pp. 72-73.

[xvi] COZMEI, Victor: Armele României (I) - Forțele Terestre: Ce arme, tancuri și blindate folosesc acum militarii români. In:Hotnews, 26 April 2019, https://www.hotnews.ro/stiri-defense-23110364-armele-romaniei-fortele-terestre-arme-tancuri-blindate-folosesc-acum-militarii-romani-plus-noi-echipamente-contureaza-pentru-viitor.htm (02.07.22)

[xvii] Nave maritime. In: Fortele Navale Romane, https://www.navy.ro/despre/nave.php (02.07.22.)

[xviii] LEIGH, David; EVANS, Rob: We paid three times too much for UK frigates, Romania says. In: The Guardian, 13 June 2006, https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2006/jun/13/armstrade.bae (02.07.22.)

[xix] Arms imports (SIPRI trend indicator values) – Romania. In: World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.MPRT.KD?end=2020&locations=RO&start=1990 (02.07.22)

[xx] SANDLER, Todd; SHIMIZU, Hirofumi: NATO Burden Sharing 1999-2010: An Altered Alliance. In: Foreign Policy Analysis, Vol. 10, 2014, pp. 43-44.

[xxi] Ibid., p. 44.

[xxii] Military expenditure. In: The World Bank.

[xxiii] Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2010-2017),

NATO Public Diplomacy Division Press Release, 29 June, 2017, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/pdf_2017_06/20170629_170629-pr2017-111-en.pdf (04.07.22), p. 5.

[xxiv] McNAMARA, Sally: NATO Summit 2010: Time to Turn Word Into Action. In: The Heritage Foundation, 10 December 2010, https://www.heritage.org/global-politics/report/nato-summit-2010-time-turn-words-action (04.07.22.)

[xxv] Military expenditure. In: The World Bank.

[xxvi] RIVOLIN, Umberto Janin: Global Crisis, Spatial Justice and the Planning Systems:

a European Comparison. In Research Gate, July 2016, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/313798739_Global_Crisis_Spatial_Justice_and_the_Planning_Systems_a_European_Comparison (02.07.22.)

[xxvii] Romania increased defense spending to 2% of GDP. In: Embassy of Romania to the USA, Romanian Foreign Ministry, https://washington.mae.ro/en/local-news/1432 (11.07.22)

[xxviii] VISAN, George: The Known Unknowns of Romania’s Defense Modernization Plans. In: ROEC, 3 March 2019, https://www.roec.biz/project/the-known-unknowns-of-romanias-defense-modernization-plans/ (11.07.22)

[xxix] JENNINGS, Gareth: Romania receives final F-16 from Portugal. In: Janes, 26 March 2021, https://www.janes.com/defence-news/news-detail/romania-receives-final-f-16-from-portugal (11.07.22)

[xxx] Romania to buy 60 new main battle tanks. In: Army Recognition, 21 November 2018, https://www.armyrecognition.com/november_2018_global_defense_security_army_news_industry/romania_to_buy_60_new_main_battle_tanks.html (11.07.22)

[xxxi] BUTIRI, Sorin: Does Romania still need tanks? In: Defense & Security Monitor, 29 October 2020, https://en.monitorulapararii.ro/does-romania-still-need-tanks-1-33968 (11.07.22)

[xxxii] Romania canceled Gowind-class corvettes project with Naval Group. In: Global Defense Corp, 22 September 2021, https://www.globaldefensecorp.com/2021/09/22/ooch-romania-cancelled-gowind-class-corvettes-project-with-naval-group/ (11.07.22)

[xxxiii] MARINAS, Radu-Sorin: Romania receives Patriot missiles from U.S. to boost defences. In: Reuters, 17 September 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-romania-defence-usa-patriot-idUKKBN2681K6 (11.07.22)

[xxxiv] CHIRILEASA, Andrei: RO army tests HIMARS multiple rocket launchers in simulated attack on Black Sea ships. In: Romania Insider, 14 June 2022, https://www.romania-insider.com/ro-tests-himars-jun-2022 (11.07.22)

[xxxv] DODGE, Michaela: A Decade of US-Romanian Missile Defense Cooperation:

Alliance Success. In: Real Clear Defense, 19 March 2021, https://www.realcleardefense.com/articles/2021/03/19/a_decade_of_us-romanian_missile_defense_cooperation_alliance_success_768925.html (11.07.22)

[xxxvi] POPESCU, Ana-Roxana: Romania to increase defence spending to 2.5% of GDP. In: Janes, 3 March 2022, https://www.janes.com/defence-news/news-detail/romania-to-increase-defence-spending-to-25-of-gdp (11.07.22)

[xxxvii] CHIRILEASA, Andrei: Romania's Govt. adopts draft bill for the purchase of 32 F-16 fighters from Norway. In: Romania Insider, 17 June 2022, https://www.romania-insider.com/romania-f16-fighters-norway-purchase (11.07.22)

[xxxviii] NEAGU, Bogdan: Romania is still committed to buy F-35s, but after 2030. In: Euractiv, 3 February 2022, https://www.euractiv.com/section/politics/short_news/romania-still-committed-to-get-f-35s-but-after-2030/ (11.07.22)

[xxxix] Piranha 5 Armored Vehicles To Be Entirely Produced At The Bucharest Mechanical Plant. In: Romania Journal, 15 March 2022, https://www.romaniajournal.ro/society-people/piranha-5-armored-vehicles-to-be-entirely-produced-at-the-bucharest-mechanical-plant/ (11.07.22)

[xl] CHIPMAN, John, et al. (eds.): The Military Balance 1990-1991 – International Institute for Strategic Studies. Brassey’s, London, 1990.

[xli] HACKETT, James (ed.): The Military Balance 2022 – International Institute for Strategic Studies. Routledge, London, 2022.