Kutatás / Geopolitika

Military modernisation in the Republic of Moldova (post-1991)

Similarly to other post-Soviet countries, the Republic of Moldova has been struggling to orient itself between the East and West since becoming independent from the USSR in the early 1990s. Moldova’s geographical (and geopolitical) proximity to Russia, as well as its internal power dynamics, Soviet bureaucratic legacy, general dependence on external powers, and the fiery way it began as a sovereign country make it both imperative and, at the same time, next to impossible to modernise its national armed forces on its own, hence the gradual decay of the Moldovan Army over the last thirty years. However, as conflict looms on the horizon, modernisation might just happen in the coming years at last.

Independence and civil war (1990-1992)

The Republic of Moldova declared independence from the Soviet Union in August 1991, and by September the same year, it also established its national armed forces. The establishment of a sovereign national military was a particularly important step for the country, as prior to that it did not have such a force on its own (since it became part of the Romanian Kingdom in the mid-1800s and annexed by Moscow after the First World War) and even before its official declaration of independence, Moldova found itself in steadily escalating conflict.

During the Soviet times, the entirety of Moldova was part of the Odesa Military District – which also comprised most of today’s South Ukraine – within the jurisdiction of the Red Army. Incorporating locally stationed elements of the Soviet forces into the army of the newly formed country after independence was simply out of question, since most military personnel based inside the MSSR belonged to the 14th Guards Combined Arms Army (in short, 14th Army), which was not only stationed in Tiraspol, the capital of the heavily Russian-populated Transnistria region but was also known to have a significant overrepresentation of Transnistrians in its ranks (with 51% of officers and 79% of the draftees coming from the region in the late 1980s).[i] This composition of the 14th Army not only ensured that the group would stay loyal to Moscow once the USSR started to break, but also that the unit would play a greater role in what was coming in the periphery of the newly formed Moldova.

As early as September 1990, Transnistria proclaimed itself an independent entity under the name Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic (PMR). While direct confrontations were rare around the border, the sudden presence of the Russian-speaking separatist state posed an increasing threat to Chișinău – forcing it to speed up its process of becoming self-governed and establishing an army. After Moldova’s independence solidified in 1991, the conflict escalated exponentially into a full-blown civil war. While at first Moscow maintained a veil of neutrality, it did, no doubt, willingly allow a great number of the 14th Army personnel to defect to the PMR’s side (including its commander), then, in mid-1992 it has officially ordered the 14th to take part in the war, effectively becoming active belligerent and turning the tide in favour of Tiraspol.[ii] Even though Romania had supported Chișinău with weapons, equipment and a small number of volunteers, and as a result, by the end of the war, the hastily conscripted Moldovan army comprised of around 12 thousand troops (with an additional 15 thousand volunteers), it was eventually overwhelmed by the 14 thousand Red Army troops, nine thousand Transnistrian militiamen and some four thousand Transnistrian volunteers by July 1992. The ceasefire agreement was signed by Chișinău and Moscow on 21 July and established the trilateral control of a joint Moldovan, Russian and Transnistrian peacekeeping mission of the border area and ensured the de facto independence of the PMR which it enjoys until today.[iii]

To summarise, Moldova – with no distinctive national military tradition – established its first modern army in the midst of an open civil war, whose baptism by fire ended with a swift military defeat and an uncertain future. After the ceasefire agreement, therefore, Chișinău’s primary objectives included a thorough upgrade of its armed forces and a development of military doctrine that could ensure the viability of the young, yet already war-torn country.

Balancing or inaction? (1992-2022)

The doctrine of ‘constitutional’ neutrality

The civil war with Transnistria, along with the fragile ceasefire agreement with Moscow and the subsequent presence of Russian military personnel within the borders of the separatist region forced Moldova to tread carefully when it comes to geopolitics, especially regarding the rising military alliances around its borders. Instead of choosing one side over the other, Moldova opted for implementing a balanced foreign policy approach complemented by a unilateral military doctrine of neutrality.

For instance, when negotiating the accession into the Russian-led economic and political bloc for post-Soviet states, the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) since late 1991, Moldova secured an opt-out from the CIS military structures and chose not to participate in any of the organisation’s military activity.[iv] Apart from the internal conflict and the domestic political turmoil it caused, this lengthy negotiation process was the reason Chișinău finalised the agreement only in April 1994. However, joining the CIS did not mean Moldova would then solely belong to the post-Soviet world and isolate itself from the West, as Chișinău simultaneously applied to NATO’s Partnership for Peace (PfP) programme, which was largely viewed by members and applicants as the first step towards becoming a full member of Washington’s primary military organisation.[v]

Moldova joined the PfP in March 1994 as the twelfth member of the programme, just a month before ratifying its CIS membership. However, unlike most of the other applicants in Central and Eastern Europe – but in accordance with its own principles – Moldovans officially voted for not going further on the road towards NATO membership at that time, but instead use the PfP solely as a platform to help strengthen Moldova’s territorial integrity, political independence and national security.[vi]

To further strengthen its neutral position, the new Moldovan constitution (adopted on 28 July 1994) declared the country’s “permanent neutrality” and claimed it would “not admit the stationing of foreign military units”, nor participate in political or military alliances “having the aim of preparing to war”.[vii] While this doctrine of permanent “constitutional” neutrality (no external guarantees or international recognition was given to it) is still in place critics say that Moldovan neutrality is not so much a strategy of balancing, but a strategy of inaction, or even a Russian tool for keeping Chișinău out of the NATO through domestic political pressure.[viii]

The following two and a half decades with regard to Moldovan military doctrine more or less meant staying on the course set in 1994. Debates around the military doctrine usually revolved around the question of how to seek good relations in the neighbourhood while not getting too close to Western powers in order to avoid tensions in the region. For instance, while maintaining its initial approach of not applying for NATO membership, Moldova participated in joint PfP operations and exercises a number of times between 1994 and 1997, both in observer and active status, it also delegated small contingencies to UN and NATO (KFOR) peacekeeping missions later. However, even after Chișinău sought to increase its military cooperation with Romania in 1997, it categorically rejected NATO application even if Bucharest would have finalised its own accession.[ix]

Military reforms, downsizing and empty promises

The legacy of the civil war also created continuous domestic political tensions in Moldova, particularly regarding the leadership aspect of the military, and subsequently, the question of spending. Since the establishment of the Ministry of Defence in 1992, its leaders were appointed from the ranks of the military high command, who tended to argue against the general reduction of the size (in both the number of troops and equipment) of the Moldovan armed forces. In 1997, however, newly elected President Lucinschi appointed Valeriu Pasat (both high-level members of the late Moldovan Communist Party) as the first civilian to be the head of the defence ministry, under whom the transition period to a civilian command of the army along with extensive reforms and downsizing promptly began – according to the neutral principles of the constitution, they argued.

The first issue the reforms addressed was the question of how much spending is the smallest optimal amount to ensure Moldova possesses enough of self-defensive capabilities and make sure of the survival of its sovereignty. Consequently, the 1997 budget was set at 70 million lei (15 million dollars), which represents a 10% cut compared to the previous year, a third of which went entirely to the joint peacekeeping mission along the Dniester. Furthermore, the new leadership announced plans to sell military property inherited from the Soviet Union at an increased pace to use the money for social security programmes. Between 1993 and 1998, Moldova sold over 60 million dollars’ worth of Soviet equipment – including 25 of its 31 MiG-29 fighter jets, along with the accompanying five hundred air-to-air missiles – most of the sales happened after the reforms of 1997.[x]

In 2002, an ambitious military reform programme was announced with three main stages in mind: development of the legal framework (2002-2004), improvement of the command-and-control system (2005-2008) and finally, the modernisation of the army (2009-2014). The third, and most important stage, however, was postponed indefinitely due to the lack of financial resources. While the Moldovan Ministry of Defence repeatedly stressed the importance of military modernisation with regard to upgrading combat readiness and replacing the scarce and outdated equipment of the army, in practice, no Moldovan government tended to give priority to the issue.[xi]

In the wake of the 2014 outbreak of conflict in the Donbas region, the Ministry of Defence announced plans to “radically” modernize the armed forces. This included replacing and upgrading old technology, increasing the size and combat readiness of troops, and allocating greater funds to national defence, as the current budget is “hardly sufficient for soldiers’ food and lodging”.[xii] Hardly any of these “radical” plans bore fruit eventually, with the exception of a few infrastructure upgrades that were initiated with the help of NATO, the UN and the United States, which primarily covered the modernisation of training centres and other installations, and not of the replacement of the old Soviet weapon system still in use in Moldova.[xiii]

The gradual decline of funds, arms and troops

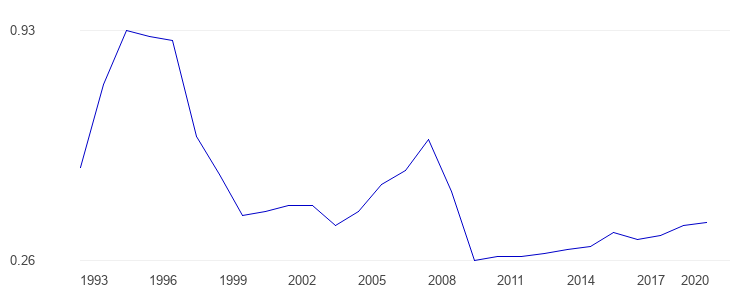

In parallel with lagging modernisation initiatives, most Moldovan governments showed no real interest to increase defence spending either. Even though the 2010s showed a slight gradual increase relative to GDP, today’s budget has dropped by almost two-thirds compared to the level of the early 1990s. In percentage of GDP, Moldovan defence spending reached its peak in 1994 with 0.93%, while by 2021 it dropped to 0.41%.[xiv] Not that there weren’t ambitious plans to substantially increase the military budget, only that these plans proposed by the defence ministry were generally discarded or significantly downgraded before being approved. For instance, the 2017 National Defence Strategy initially outlined the reaching of 0.5% of the GDP by 2020 and a steady, gradual increase after that until the European average of 1.4% is met. After revisions by the Ministry of Finance, however, the final figures showed 0.4% by 2020 and 0.52% by 2025 (the first stage of which was only met in 2021).[xv]

Moldovan defence spending in percentage of GDP, 1993-2020

(The Global Economy, 2022)

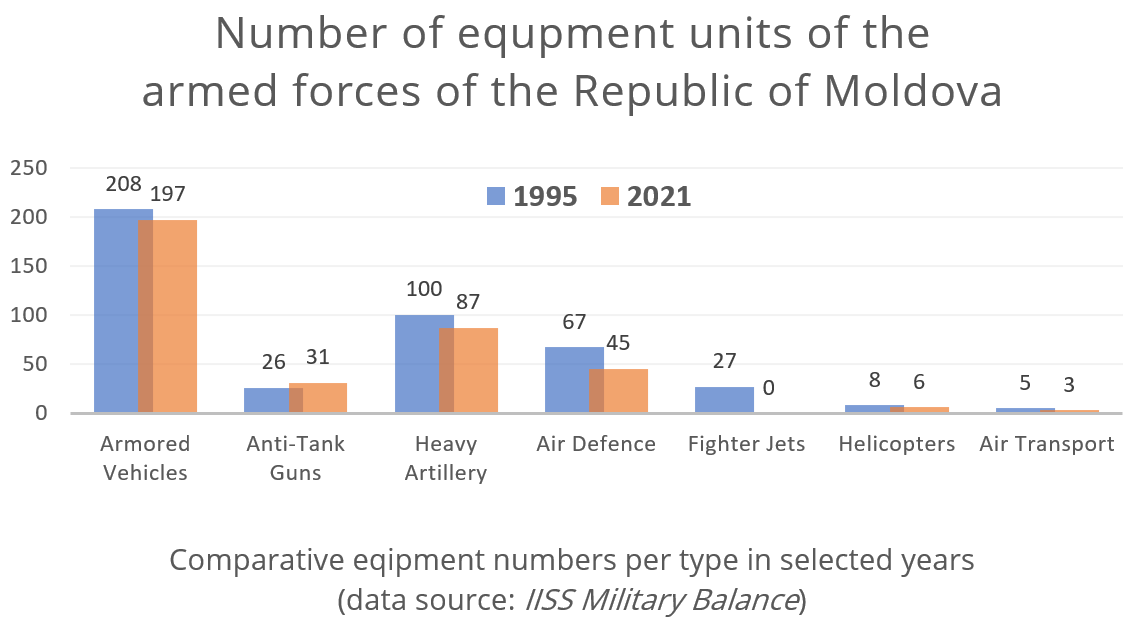

The lack of available funds directly impacted the state of the equipment of the armed forces, which had not been improved in thirty years. But budgetary issues are only one of the reasons behind not having ample equipment; another one is the 1990s’ governments practice of getting rid of whatever could be sold from the old Red Army inventories (as mentioned above) – usually blaming maintenance costs – as well as the fact that upon separation, Tiraspol had much greater access to the pre-1991 Soviet weapon depots, so Chișinău did not inherit enough of the USSR’s combat weaponry to begin with. In 1995, for instance, the Moldovan ground forces’ most valuable pieces were the 208 armoured fighting vehicles (including 54 BMD-1, 71 TAB-71 and 59 MT-LB types) – and not a single battle tank. Furthermore, the ground forces had 71 towed artillery units (mainly D-20 and 2A36), fifteen rocket systems (9P140 Uragan units), 26 towed anti-tank guns, and 42 air defence guns – all of which were already considered outdated technology manufactured in the ‘60s and ‘70s. The air force consisted of the 27 MiG-29 fighter jets (four already sold to Yemen), eight Mi-8 helicopters, five carrier aircrafts, and 25 SA-3 Goa and SA-5 Gammon surface-to-air missile systems.[xvi]

By 2021, in contrast, the overall numbers have only decreased (with the exception of the MT-12 Rapira Soviet anti-tank guns, of which four more have been acquired) and no newer weapon systems have been added to the Moldovan armed forces’ inventory. For instance, Moldova had sold or scraped all of its fighter jets and almost all of its surface-to-air missile systems, as well as eleven armoured fighting vehicles, two helicopters, two carrier aircrafts, and several of its artillery and air defence units.[xvii]

With regard to acquiring troops, Moldova had plans to scrape the Soviet-era conscription as early as 1991, but the civil war and tensions of the following years kept the institution in place for way longer than expected. Twelve months of military service is still obligatory for all males, but it is reduced to three months for university graduates. In June 2018, the parliament approved a specific modernisation programme, which aimed at following through with the transition into an entirely professional army by the end of 2021, however – due to budgetary reasons, the impact of the pandemic, and now the situation in Ukraine – conscription is still the most relied-on method to fill up the ranks.[xviii]

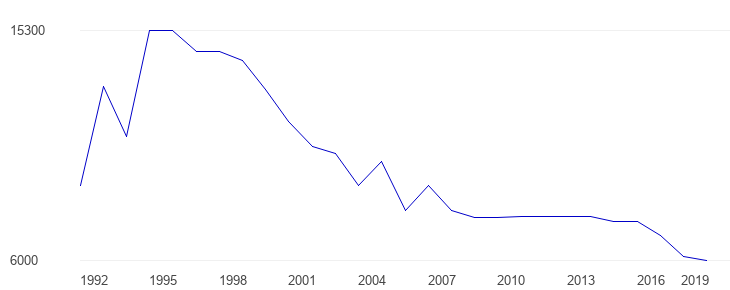

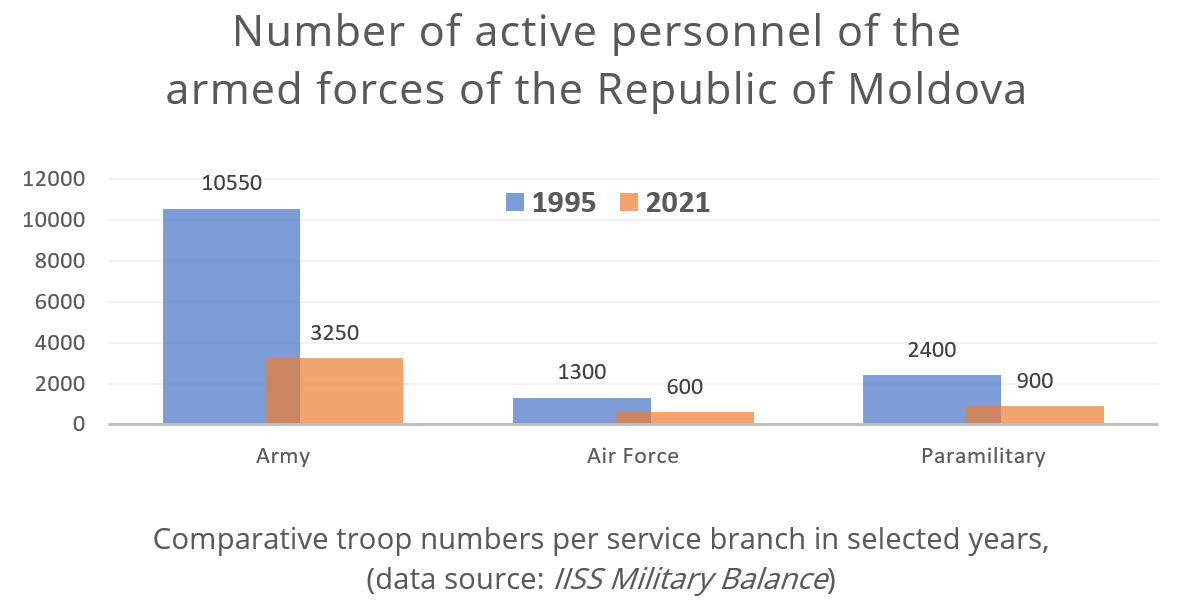

In terms of numbers, the Moldovan armed forces reached its peak in 1995 (with more than fifteen thousand servicemen and 66 thousand reservists), but especially after the reforms of 1997, troop numbers began to drop steadily over the decades. By the early 2000s, the number of active military personnel dropped under ten thousand, and as of now, the Moldovan armed forces consist of only 5,150 active members (including 1,650 professionals, 2,200 conscripts, nine hundred paramilitary, and 1,300 logistic support personnel) along with 58 thousand in reserves.[xix]

Number of active personnel in the Moldovan armed forces, 1992-2019

(The Global Economy, 2022)

By most metrics, the Moldovan armed forces are significantly underdeveloped and ill-equipped compared to the armies of any neighbouring countries and possible adversaries in the region (meaning primarily Russia and the Russian-backed PMR), they are simply unfit to carry out prolonged combat duties even when it would come to defending the country. Moreover, not only have the majority of reservists not been trained for more than 25 years, but Moldova is not even close to being able to provide equipment for all of them in case of sudden mobilisation.[xx]

Preparing for the inevitable (post-2022)

Many international experts saw the victory of the pro-Western politician Maia Sandu over the communist Igor Dodon in the battle for the presidential seat in late 2020 as a turning point for Moldova, as Sandu ran an explicitly anti-corruption campaign that mainly addressed the de-platforming of the Russian-influenced oligarchy infused within the ranks of previous governments.[xxi] President Sandu was expected to challenge the entire status quo with a more Western- (and NATO-) oriented approach, which also opened up new opportunities regarding military modernisation, which previously was stalled – at least partly – due to the extent of corruption and foreign, mostly Russian interests. Just days after her election victory, President Sandu met with NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg to discuss deeper cooperation with the Atlantic Organization and “to begin the process of modernizing the national army”,[xxii] yet, because of the large number of policy areas in need of thorough reform, significant changes did not occur within the Moldovan armed forces during the first two years of her presidency either. But then Russia attacked Ukraine in February 2022, which called for sudden strategic upgrades throughout Central and Eastern Europe.

‘Risk-averse’ policy and the new case for neutrality

Debates around Moldova’s constitutional neutrality were immediately restarted after the Russian aggression on Ukraine – just as they did after the annexation of Crimea, albeit with no result. Back then, most pro-Western politicians argued for the reconsideration of the 1994 articles on permanent neutrality and a gradual rapprochement to NATO, as only closer ties to the Atlantic Organization could help the country modernise swiftly enough to meet the new defence requirements. The members of the Communist Party, on the other hand, frequently called out against such closer cooperation, saying that it would only escalate the existing tensions, and instead, they emphasised the need for security guarantees that would facilitate the international recognition of Moldovan neutrality.[xxiii] Critics of this rhetoric, of course, pointed out, that such a scenario would effectively exclude any future possibility of the country’s NATO accession, an undoubtedly positive outcome for Vladimir Putin’s Russia.[xxiv]

With a full-blown war next door, however, the situation seems to have changed quite a bit. The governing Party of Action and Solidarity and President Sandu, along with the majority of the population, now firmly support the existing policies of neutrality and even made them central in the current foreign policy strategy. The president’s so-called “risk-averse policy” basically imposes a strict self-restraint on political statements and an effective embargo on any political move that could potentially provoke Russia. This policy, along with the economic costs, was also the reason Chișinău is still reluctant to join the Western sanctions against Russia.[xxv]

Nevertheless, even if the idea of NATO accession is off the table for the time being, the government is still pushing for EU membership, since funds from Brussels could come very useful in regard to military modernisation as well. The support for reunification with Romania has also grown considerably in recent months since such a scenario would instantly put the whole European integration process behind Moldova, but it would also mean ditching neutrality for immediate NATO membership, which would undermine the president’s and governing party’s current narrative about the utmost importance of “risk-aversion”. Chances for reunification, however, much for these exact reasons on both sides of the border, are negligible.[xxvi]

Military modernisation – at last

In fact, the European Union is already among the closest partners in upgrading the Moldovan armed forces. After reports of explosions near Tiraspol (which had been suspected to be Russian false-flag attacks) and the subsequent order of general mobilisation in the breakaway region of Transnistria in late April,[xxvii] President of the European Council Charles Michel announced on 4 May 2022 that the EU will provide substantial economic and political support for Moldova in the form of opening up the European energy procurement platform and the shipment of additional military equipment (for strictly defence purposes). Presidents Sandu and Michel also agreed to draft a bill aimed at “strengthening the neutrality of the country” that would ban the deployment of foreign troops and weapons in Moldova, which could constitute the first step toward wider international recognition of the country’s so far only unilaterally declared neutrality.[xxviii]

A few weeks later, on 20 May 2022, British Foreign Secretary Liz Truss also announced that the UK and its allies (primarily meaning a joint commission with Poland and Ukraine) have begun discussions about considerable arms shipments to Moldova. Recognising the important geostrategic position of the country as well as the historically neglected state of its armed forces and the implications of this in relation to the ongoing conflict in Ukraine, the foreign secretary said they would aim to “see Moldova equipped to NATO standards”.[xxix] Details are yet to be specified, but the statement clearly indicates that this would mean a complete overhaul of Moldovan defence capabilities, quite probably including lethal armaments as well.

Conclusions

The Republic of Moldova was immediately pulled into conflict upon declaring independence from the USSR with the breakaway region of Transnistria acting as a Russian proxy, which forced the newly formed state to build up its armed forces from scraps – keeping conscription and using old Soviet weaponry. After the ceasefire agreement of 1992 – and especially after the armed forces had been placed under civilian command in 1997 – however, nearly all subsequent Moldovan governments neglected or even actively sought to downgrade the military in terms of budget, personnel, and equipment alike, citing financial and geopolitical reasons. Historically, Moldova’s official doctrine of unilateral “constitutional” neutrality did not contribute to the development of a strong military force (as was the case of Switzerland or Finland, for instance), but quite the contrary: it was used as the ultimate political argument against military modernisation.

Over the decades, these factors resulted in a steady decay of the Moldovan armed forces, to the point where it is effectively unable to meet the most basic defensive requirements, would the need ever arise. Compared to 1995 levels, the defence spending (relative to GDP) has decreased by 56%, the number of active personnel dropped by 66%, and on average, the number of heavy weaponry per type decreased by around 30%. Furthermore, all of the equipment that is still in use in the Moldovan armed forces are highly outdated Soviet military technologies, as no newer models were purchased whatsoever to complement the initial inventory (inherited from the USSR), and the country does not have independent military-industrial capabilities to produce its own.

Nevertheless, the war in Ukraine has presented ample reason for Western powers to help Moldova modernise its armed forces, which is likely to begin in the following months and years. However, the utter negligence of Moldovan officials in this matter over the last three decades makes this project a much greater challenge than it would have been otherwise, and there might not be enough time before Russia or the Moscow-backed separatists in Transnistria decide to reheat the conflict.

Bibliography

- BADSHAH, Nadeem: UK and allies discuss arming Moldova with ‘NATO standard’ weapons. In: The Guardian, 20 May 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2022/may/20/uk-and-allies-discuss-arming-moldova-with-nato-standard-weapons (22.05.22.)

- CALUGEREANU, Vitalie; SCHWARTZ, Robert: As Ukraine rages next door, Moldova is building up arms. In: Deutche Welle, 20 April 2015, https://www.dw.com/en/as-ukraine-rages-next-door-moldova-is-building-up-arms/a-18395134 (22.05.22.)

- CHIPMAN, John, et al. (eds.): The Military Balance 1995-1996 – International Institute for Strategic Studies. Oxford University Press, London, 1995.

- DE LA PEDRAJA, René: The Russian Military Resurgence: Post-Soviet Decline and Rebuilding, 1992-2018. McFarland, Jefferson, 2018.

- EU to support Moldovan army — but opposition Socialists call for Russian military presence. In: Intellinews, 5 May 2022, https://intellinews.com/eu-to-support-moldovan-army-but-opposition-socialists-call-for-russian-military-presence-243412/?source=moldova (22.05.22.)

- HACKETT, James (ed.): The Military Balance 2021 – International Institute for Strategic Studies. Routledge, London, 2021.

- HACKETT, James (ed.): The Military Balance 2022 – International Institute for Strategic Studies. Routledge, London, 2022.

- KIRVELYTĖ, Laura: Moldova’s Security Strategy – The Problem of Permanent Neutrality. In: Lithuanian Annual Strategic Review, 2010.

- LINS DE ALBUQUERQUE, Adriana; HEDENSKOG, Jakob: Moldova – A Defence Sector Reform Assessment. FOI, Stockholm, 2016.

- MARIN, Danu: Evolution in Moldova security sector – Prospects for the future. In: EaP Think Bridge, No. 10, October 2017.

- MILEWSKI, Oktawian: Challenging the status quo in Moldova. What now after Maia Sandu’s victory? In: New Eastern Europe, 1 December 2020, https://neweasterneurope.eu/2020/12/01/challenging-the-status-quo-in-moldova-what-now-after-maia-sandus-victory/ (22.05.22.)

- Moldova Economic Indicators. In: The Global Economy, 2022, https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/Moldova/ (22.05.22.)

- MUNTEANU, Igor: Moldova: living at the edge of war.

In: International Politics and Society,

29 March 2022, https://www.ips-journal.eu/topics/foreign-and-security-policy/moldova-living-at-the-edge-of-war-5836/ (22.05.22.) - NATO va sprijini modernizarea instituțiilor de securitate și apărare ale R. Moldova. In: Timpul, 6 January 2021, https://timpul.md/articol/nato-va-sprijini-modernizarea-institutiilor-de-securitate-si-aparare-ale-r-moldova-162155.html (23.05.23.)

- NECSUTU, Madalin: Moldova’s Breakaway Transnistria Orders General Mobilisation. In: Balkan Insight, 28 April 2022, https://balkaninsight.com/2022/04/28/moldovas-breakaway-transnistria-orders-general-mobilisation/ (22.05.22.)

- ORBÁN, Tamás: Thirty years of Visegrad summits and themes of a Central European cooperation. In: Anton Bendarzsevszkij (ed.): 30 years of the V4. Danube Institute, Budapest, 2021.

- OZHIGANOV, Edward: The Republic of Moldova: Transdniester and the 14th Army. In: Alexei Arbatov, et al. (eds.): Managing Conflict in the Former Soviet Union: Russian and American perspectives. MIT Press, Cambridge, 1998.

- SANCHEZ, Wilder Alejandro: Assessing a Possible Moldova-Romania Reunification. In: Geopolitical Monitor, 6 January 2022, https://www.geopoliticalmonitor.com/assessing-a-possible-moldova-romania-unification/ (23.05.22.)

- SANCHEZ, Wilder Alejandro: Moldovan military relies on partnerships for modernisation. In: Shephard, 14 September 2021, https://www.shephardmedia.com/news/defence-notes/moldovan-military-relies-partnerships-modernisatio/ (22.05.22.)

- SHOEMAKER, M. Wesley: Russia and the Commonwealth of Independent States. Stryker Post, Stryker, 2012.

- WALTERS, Trevor: The Republic of Moldova: Armed forces and military doctrine. In: The Journal of Slavic Military Studies, Vol. 11, Issue 2, 1997.

[i] OZHIGANOV, Edward: The Republic of Moldova: Transdniester and the 14th Army. In: Alexei Arbatov, et al. (eds.): Managing Conflict in the Former Soviet Union: Russian and American perspectives. MIT Press, Cambridge, 1998, p. 179.

[ii] DE LA PEDRAJA, René: The Russian Military Resurgence: Post-Soviet Decline and Rebuilding, 1992-2018. McFarland, Jefferson, 2018, pp. 93-94.

[iii] WALTERS, Trevor: The Republic of Moldova: Armed forces and military doctrine. In: The Journal of Slavic Military Studies, Vol. 11, Issue 2, 1997, p. 81.

[iv] SHOEMAKER, M. Wesley: Russia and the Commonwealth of Independent States. Stryker Post, Stryker, 2012, p. 181.

[v] ORBÁN, Tamás: Thirty years of Visegrad summits and themes of a Central European cooperation. In: Anton Bendarzsevszkij (ed.): 30 years of the V4. Danube Institute, Budapest, 2021, p. 13.

[vi] WALTERS, p. 81.

[vii] Ibid., p. 83.

[viii] LINS DE ALBUQUERQUE, Adriana; HEDENSKOG, Jakob: Moldova – A Defence Sector Reform Assessment. FOI, Stockholm, 2016, p. 24.

[ix] WALTERS, pp. 83-85.

[x] Ibid., p. 85.

[xi] LINS DE ALBUQUERQUE; HEDENSKOG, pp. 30-31.

[xii] CALUGEREANU, Vitalie; SCHWARTZ, Robert: As Ukraine rages next door, Moldova is building up arms. In: Deutche Welle, 20 April 2015, https://www.dw.com/en/as-ukraine-rages-next-door-moldova-is-building-up-arms/a-18395134 (22.05.22.)

[xiii] SANCHEZ, Wilder Alejandro: Moldovan military relies on partnerships for modernisation. In: Shephard, 14 September 2021, https://www.shephardmedia.com/news/defence-notes/moldovan-military-relies-partnerships-modernisatio/ (22.05.22.)

[xiv] HACKETT, James (ed.): The Military Balance 2022 – International Institute for Strategic Studies. Routledge, London, 2022, p. 191.

[xv] MARIN, Danu: Evolution in Moldova security sector – Prospects for the future. In: EaP Think Bridge, No. 10, October 2017, p. 20.

[xvi] CHIPMAN, John, et al. (eds.): The Military Balance 1995-1996 – International Institute for Strategic Studies. Oxford University Press, London, 1995, p. 91.

[xvii] HACKETT, 2022, p. 192.

[xviii] HACKETT, James (ed.): The Military Balance 2021 – International Institute for Strategic Studies. Routledge, London, 2021, p. 189.

[xix] HACKETT, 2022, p. 191.

[xx] LINS DE ALBUQUERQUE; HEDENSKOG, p. 27.

[xxi] MILEWSKI, Oktawian: Challenging the status quo in Moldova. What now after Maia Sandu’s victory? In: New Eastern Europe, 1 December 2020, https://neweasterneurope.eu/2020/12/01/challenging-the-status-quo-in-moldova-what-now-after-maia-sandus-victory/ (22.05.22.)

[xxii] NATO va sprijini modernizarea instituțiilor de securitate și apărare ale R. Moldova. In: Timpul, 6 January 2021, https://timpul.md/articol/nato-va-sprijini-modernizarea-institutiilor-de-securitate-si-aparare-ale-r-moldova-162155.html (23.05.23.)

[xxiii] CALUGEREANU; SCHWARTZ.

[xxiv] KIRVELYTĖ, Laura: Moldova’s Security Strategy – The Problem of Permanent Neutrality.

In: Lithuanian Annual Strategic Review, 2010, pp. 165-169.

[xxv] MUNTEANU, Igor: Moldova: living at the edge of war. In: International Politics and Society,

29 March 2022, https://www.ips-journal.eu/topics/foreign-and-security-policy/moldova-living-at-the-edge-of-war-5836/ (22.05.22.)

[xxvi] SANCHEZ, Wilder Alejandro: Assessing a Possible Moldova-Romania Reunification. In: Geopolitical Monitor, 6 January 2022, https://www.geopoliticalmonitor.com/assessing-a-possible-moldova-romania-unification/ (23.05.22.)

[xxvii] NECSUTU, Madalin: Moldova’s Breakaway Transnistria Orders General Mobilisation. In: Balkan Insight, 28 April 2022, https://balkaninsight.com/2022/04/28/moldovas-breakaway-transnistria-orders-general-mobilisation/ (22.05.22.)

[xxviii] EU to support Moldovan army — but opposition Socialists call for Russian military presence. In: Intellinews, 5 May 2022, https://intellinews.com/eu-to-support-moldovan-army-but-opposition-socialists-call-for-russian-military-presence-243412/?source=moldova (22.05.22.)

[xxix] BADSHAH, Nadeem: UK and allies discuss arming Moldova with ‘NATO standard’ weapons. In: The Guardian, 20 May 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2022/may/20/uk-and-allies-discuss-arming-moldova-with-nato-standard-weapons (22.05.22.)